The Russian Brusilov Offensive in summer 1916: History, preparation and conduct of the most successful Russian offensive in World War One, which probably averted an Allied defeat.

The Russian Brusilov Offensive from 1916

Table of Contents

The Brusilov Offensive was a major military operation conducted by the Russian Empire against Austria-Hungary during World War I. It took place from June to September 1916 and is considered one of the most successful offensives of the war.

Overview

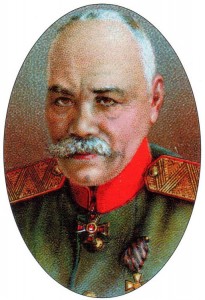

Leadership: The offensive was led by General Aleksei Brusilov, commander of the Russian Southwestern Front.

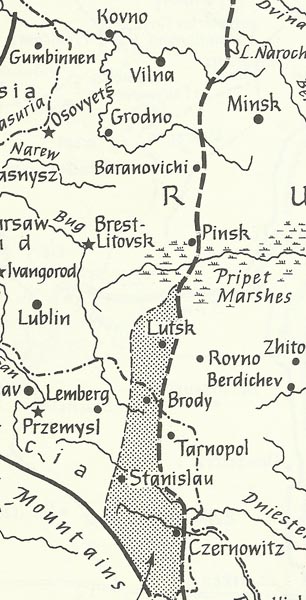

Location: It took place along a 300-mile front in Galicia and Bukovina (modern-day Ukraine and Romania).

Objectives: The primary goals were to relieve pressure on other Allied fronts and to knock Austria-Hungary out of the war.

Tactics: Brusilov employed innovative tactics, including:

– Short, intense artillery bombardments

– Multiple, simultaneous attacks along the front

– Shock troops to exploit weak points

Initial success: The offensive caught the Austro-Hungarian forces off guard and made significant territorial gains.

Casualties: Both sides suffered heavy losses. Estimates vary, but total casualties (killed, wounded, and captured) were around:

– Central Powers: 1.5 million (mostly Austro-Hungarian)

– Russian Empire: 500,000 – 1 million

Strategic impact:

– Forced Germany to divert forces from the Western Front

– Weakened Austria-Hungary significantly

– Prompted Romania to enter the war on the Allied side

Long-term consequences:

Despite initial success, Russia couldn’t capitalize on its gains due to logistical issues and lack of reserves. The offensive contributed to the exhaustion of the Russian army, which played a role in the subsequent Russian Revolution.

Historical significance: The Brusilov Offensive is considered one of the most lethal offensives in world history and a prime example of breakthrough tactics that would later be developed in World War II.

While the Brusilov Offensive achieved significant tactical success, it did not lead to a strategic victory for Russia or the Allies. Nevertheless, it remains a notable military operation that had far-reaching consequences for the course of World War I.

Prehistory to Brusilov offensive

To the north had been the North-West Front, commanded by the similar Kuropatkin who in the 1905 Russo-Japanese War became a professional in the technique of the retreat in the wrong moment. The following army group was the West Front leaded by General Evert, who had been likewise to reveal a hate for offensive steps. Eventually there was the South-West Front led by one more expert of scare, General Ivanov.

Major-General Alexeyev who, as CoS to the C-in-C Tsar Nicholas, was in command of the Russian operations, had been amongst the best officers of World War One – however his front army generals undoubtedly were not.

That soldiers of their mindset were placed at such sensible positions was, on one side, an indictment of the Russian interior governmental condition: with the Tsar, weak-willed in any event, away from contact from the front, the practice of issues at St Petersburg had been based increasingly more on the intrigues of the Tsarina as well as her favorites, and this group maintained to oppose the appointment of gentlemen associated with intellectual power as well as sturdy character.

At the same time, there seemed to be one more reason why countless Russian generals had been inactive: the triumph of 1812 over Napoleon had these days, assisted by Tolstoy’s amazing and mistaken understanding in the best-seller War and Peace, joined the Russian myth like a triumph earned by an outstanding general known as Kutuzov who had intentionally retreated to be able to win the struggle. As a result there were around an idea – aware as well as subconscious – of success by retreat, and that’s why plenty of Russian leaders appeared unwilling and over-anxious in offensive.

Throughout the wintertime of 1915-16 the Russian troops had been gradually recovered to battling state. The inefficiencies of 1915, insufficient weapons, of ammo, of shoes, as well as well-trained men, wouldn’t be recurring in 1916. At the beginning of 1916 firearms were manufactured at the amount of Ten Thousand monthly; numerous front-line troops had their complete supplement of machine-guns and field howitzers; ammo, apart from possibly for the biggest artillery pieces, ammo had been supplied quick enough to create stocks for a complete summertime campaign; the silent winter season had provided some time for correct exercising of new soldiers.

However, the lack of properly skilled officers couldn’t be solved so simply.

The Red Cross detachments set up by regional citizens were undertaking a lot to maintain front-line spirits, not least since they made it their work to maintain most of the recreational and physical requirements which the war ministry had so obviously ignored.

The final struggle of 1915 had been a modest Russian attack in the south, directed at assisting the Serbian army, which had been forced into retreat when Bulgaria proclaimed war.

During the cold months an inter-Allied military convention placed at Chantilly in France built strategies for the 1916 summertime campaign. Russia was to perform a comparatively minor component in these strategies, due to the serious casualties she had suffered in 1915: the primary Allied attack was to perform the Somme, and was to be preceded by a minimal diversionary offensive performed by the Russian troops.

However, the German army disrupted this strategy by their big strike on Verdun since February: certainly not the very first time – nor the final – Russia had been asked in order to save her western allies by developing a hastily-planned attack to attract German divisions from France to Russia.

In March and April a Russian army of the West Front, with artillery support whose power stunned the German troops, assaulted through the dirt of the spring thaw and overrun the German advanced trenches. Ludendorff raised reinforcements, for reasons unknown the STAVKA withdrew the Russian heavy guns and planes from the area, and the Russian troops had been positioned virtually defenseless in light marsh ditches, without gas masks. Struggling to the continuous onslaught of high-explosive and gas shells, and suffering huge casualties, the Russian soldiers, even now performing their songs, had been pushed returning to their starting point in a single day.

This tragedy in the battle of Lake Naroch, had been a comparatively small battle, and the Russians had been immediately arranging more impressive plans, equally to honor their promise to the Allies, because the Somme offensive was still timetabled – as well as carry burden off the French army, who were suffering serious casualties and in an urgent position at Verdun.

On April 14 the Tsar had presided at a conference of the front commanders at STAVKA. By this point the morbid Ivanov had been sacked and General Alexey Brusilov took over, who as an army general had distinguished himself in the 1915 retreat despite the fact that he had been a professional of an offensive strategy.

Preparation of the Brusilov offensive

During the April 14 conference the concept of an offensive of Evert’s West Front had been talked about. The two Ruropatkin as well as Evert said that they recommended remaining on the defensive, claiming that there wasn’t adequate heavy guns as well as ammunition to begin an attack.

Brusilov could not agree, and suggested assaults along the full frontline. This last mentioned suggestion was made in opinion of the advanced rail communications on the German side of the frontline. By rapidly transferring soldiers from a silent area the German generals could comfortably strengthen that section of their frontline threatened by the Russians. If the Russian strike emerged not at a single place but at a number of points, this would be trickier, particularly as it would be difficult to predict which of the assaults had been developed to grow into the chief push.

It had been ultimately decided that an attack would be started at the end of May, and that Brusilov’s South-West Front would create the first push however that the primary drive would actually begin shortly later on Evert’s West Front and be aimed towards Wilno.

While he left this conference Brusilov had been informed by an associate that he had been foolish to risk his status by providing to start an attack. Unperturbed with this pessimism, he came back to his South-West Front headquarters to make the best of his 6-week preparation period. He chose not to concentrate his troops however to request each one of the 4 generals leading his armies to arrange an assault; with arrangements being prepared at several locations on his Two hundred mile front the opponent would be helpless to anticipate where the main strike would come.

In the past, as Brusilov had been conscious, both the time and the place of an offensive had appeared to generate no surprise to the enemy, so, along with staying away from troop deployments, he took the safety measures of sending away the newspaper correspondents. Furthermore, considering that he believed that the Tsarina had been a foolhardy talker, he stayed clear of informing her the specifics of his strategy.

The Austro-Hungarian frontline which Brusilov had been getting ready to crack had been solidly prepared, comprised in many sections of 3 defensive lines one behind another at distances of 1 or even 2 miles (3.22 km).

Each line had a minimum of 3 full-depth trenches, with 50 to 60 yds between each trench. There were properly constructed machine-gun nests, dugouts, sniper hideouts, and as plenty of connecting ditches as were necessary. In front of each line there was a barbed wire obstacle, made up of about 20 rows of posts to which were attached swathes of barbed wire, several of which had been really solid and several mined or electrified.

Brusilov’s planes had pictured fine photos of those defenses and the information had been used in large-scale maps so that, as was demonstrated afterwards, the Russian officers had maps of the same quality of the enemy frontline as had the Austro-Hungarian. Moreover, despite the fact that throughout the planning time the majority of the men had been held properly at the rear of the frontline, the Russian officers spent a lot of time in advanced trenches checking out the ground over which they would attack. Meanwhile, with unique sighting shots the gunners could actually find the range of their upcoming targets, and shell stocks had been increase. Ditches to provide as deployment and attacking spots had been created close to the front-line Austro-Hungarian frontline, occasionally being as near as between 100 and 75 yds. Since this was to be an extensively distributed undertaking and never a regular full-strike assault, absolutely no reserves had been deployed.

During the time his 4 army generals had been each arranging the details of their respective assaults, Brusilov was in contact – frequently acrimonious contact – with STAVKA about the issue of timing.

On one side, Evert had been announcing that his West Front offensive, for which Brusilov’s was simply a preliminary diversion, required additional preparation days. On the contrary, to the crisis at Verdun was right now included the retreat of the Italians by the Austro-Hungarian troops at Trentino: except if Russia could carry out an offensive to reduce the burden Italy could be pushed from the war and the Central powers would be able to carry increased energy towards Verdun.

Eventually, the attack was started on June 4. It was later called the ‘Brusilov’s Offensive’, which was the sole triumph in World War One, which was titled after it’s general.

Brusilov Offensive Forces June 4, 1916:

Russian Forces:

Army | Infantry divisions | Cavalry divisions | Soldiers | Guns |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Eight Army | 11 | 4 | 200,000 | 716 |

Eleventh Army (Sakharov) | 8 | 1 | c.125,000 | 200 |

Seventh Army (Scherbachev) | 7 | 3 | c.125.000 | ? |

Ninth Army (Leschitski) | 10 | 4 | 150,000 | 495 (47 heavy) |

TOTAL Southwest Front (Brusilov) | 40 | 15 | over 600,000 | 1,938 (incl 168 heavy) |

Austro-Hungarian Forces:

Army | Infantry divisions | Cavalry divisions | Soldiers | Guns |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Fourth Army (Archduke Frederick) | 12 | 4 | 150,000 | 549 (incl 174 heavy) |

First Army (Duhallo) | 3 | 1 | ? | ? |

Second Army (Boehm-Ermolli) | 5 | 1 | ? | ? |

German Suedarmee (Bothmer) | 6 (+ German 48th Reserve division as reserve) | - | ? | ? |

Seventh Army (Pflanzer-Baltin) | 12 | 5 | 107,000 | 150 (medium and heavy) |

TOTAL Austro-Hungarian Army Group (Archduke Friedrich) | 38 1/2 (incl 2 German) | 11 | c.500,000 | 1,846 (incl 545 heavy) |

The Brusilov Offensive

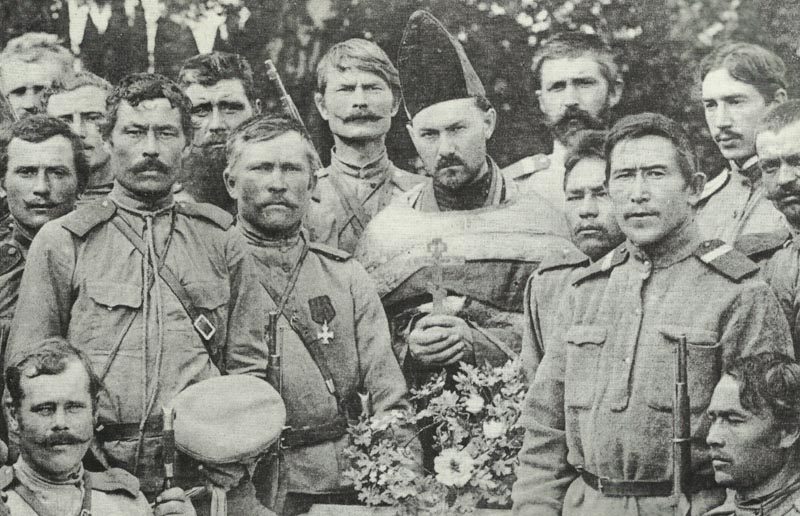

3 of Brusilov’s 4 armies broke through immediately, helped by careful artillery fire, shock, as well as the happiness with which the Czech units of the Austro-Hungarian divisions presented themselves as pleased PoWs.

Brusilov’s principal push was in the direction of Rovel and Lutsk. The latter was captured on June 8. Archduke Josef Ferdinand was forced by Russian fire to cancel his birthday celebration which he was enjoying at Lutsk.

Along with 3 wide and deep holes in their frontline the Austro-Hungarian were rapidly entirely as well as quickly retreat.

Nevertheless, the fearful Evert was continued too hesitant to begin his own offensive and on June 9 Brusilov found out that this strike would be delayed until June 18. By now Ludendorff was urgently wanting to arrange a counter-attack, and deploying all available German models which he could transfer south to stiffen the demoralized Austro-Hungarian armies.

Luckily for Austro-Hungarian, Brusilov’s primary drive, mislead by confusing orders from STAVKA, moved in 2 different directions at the same time, and for that reason wasted the possibility of conquering Rovel.

On June 18 Evert’s guaranteed offensive in the direction of Wilno didn’t begin. Instead, he launched a small, ill-prepared, not to mention failed attack farther south at Baranowicze.

These days it had been obvious that STAVKA would likely carry out what Brusilov had constantly opposed: rather than assaulting on the West Front it would dispatch Evert’s soldiers to Brusilov, hoping that the latter with these units would be able to take advantage of his first success.

But as Brusilov predicted, the moment the Germans observed these Russian troop transfers they believed in a position to send their own soldiers southwards and, simply because they had superior railways, arrived first. In this manner the German generals were able to get the best potential use of their limited troops.

Regardless of a new drive at the end of July, Brusilov created much less progress as he met increasingly more German soldiers opposing his Russian troops. Generally speaking, the Brusilov Offensive came to a close around August 10, by which moment the Austro-Hungarian had lost not simply large regions of land but additionally 375,000 PoWs, not to mention of wounded and killed soldiers.

However, Russian deaths currently overtaken 500,000 men.

Brusilov afterwards stated that if his extremely victorious attack had been effectively used, Russia could have won World War One for the Allies. It does appear really likely that if Evert had executed the primary offensive as intended, and so occupying those German soldiers which actually were transferred to boost the Austro-Hungarian army, Brusilov could have been in a position to push Austro-Hungarian out of the war. And this could practically undoubtedly would have followed by the give up of Germany prior to the end of 1916, like it happened finally in 1918.

In any event, Brusilov’s Offensive reached all the goals which it had been placed, even more: Austrian units in Italy were forced to drop their triumphs and hurry northeast to deal with the Russians, as well as the Germans were forced to last part the Verdun offensive and send at least 35 divisions from the West to the East. Even if Brusilov offensive hadn’t won World War One, he most likely halted the Allies losing it.

Brusilov Offensive Losses June 4 – October 18, 1916:

Losses:

| Soldiers | Equipment | |

|---|---|---|

| Germans | 150,000 (by August 31) | (included with Austro-Hungarian) |

| Austro-Hungarian | 750,000 (incl 380,000 PoWs) | 405 guns, 1.326 MGs, 367 mortars (by August 12 for Germans and Austro-Hungarian together) |

| Turkey | over 17,792 | ? |

| Russia | 1,412,000 (incl 212,000 PoWs) | ? |

References and literature

Illustrierte Geschichte des Ersten Weltkriegs (Christian Zentner)

History of World War I (AJP Taylos, S.L. Mayer)

Der Erste Weltkrieg – Storia illustrata della Prima Guerra Mondiale (Hans Kaiser)

Der I. Weltkrieg – Eine Chronik (Ian Westwell)

Chronicle of the First World War, 2 Bände (Randal Gray)

Unser Jahrhundert im Bild (Bertelsmann Lesering)