Dardanelles Campaign 1915: Key Strategies and Failures of the Allied Naval Assault.

The Dardanelles campaign and Gallipoli

Table of Contents

The Dardanelles Campaign, launched in February 1915, was a bold but ultimately unsuccessful Allied attempt to break through the strait connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Black Sea during World War I. British and French naval forces began the operation on February 19, hoping to force their way through the narrow channel and eventually capture Constantinople, the capital of the Ottoman Empire. After the naval assault failed on March 18, Allied forces initiated an amphibious landing on the Gallipoli peninsula on April 25, 1915, marking the first major amphibious operation in modern warfare.

The campaign represented a strategic attempt to knock Turkey out of the war and open a supply route to Russia. Allied planners believed success would change the course of the war, but they underestimated Turkish defenses and resolve. What was intended as a swift naval victory evolved into a prolonged land campaign on the Gallipoli peninsula that would last until January 1916.

Turkey, supported by German military advisors, mounted a fierce defense that stopped the Allied advance. The challenging terrain, effective Turkish resistance, and poor planning contributed to the campaign’s failure. This costly endeavor resulted in hundreds of thousands of casualties on both sides before the Allies eventually withdrew, leaving the Dardanelles firmly under Turkish control.

Historical Context

The Dardanelles Campaign unfolded within a complex geopolitical backdrop that shaped military decisions in 1915. The strategic importance of the region and the outbreak of World War I created conditions that made the Dardanelles a critical target.

Pre-War Strategic Importance

The Dardanelles Strait formed a crucial waterway connecting the Aegean Sea to the Sea of Marmara, and ultimately to the Black Sea. This narrow passage was vital for controlling access between Europe and Asia.

Control of the Dardanelles meant control of Constantinople (now Istanbul), the capital of the Ottoman Empire. For centuries, major powers coveted this region for its ability to restrict naval movement and trade.

Russia particularly depended on the Dardanelles for warm-water access to global shipping lanes. Nearly 40% of Russian exports passed through this strait before the war.

The Ottoman Empire had fortified the region extensively, recognizing its vulnerability and strategic value. These fortifications would later pose significant challenges to Allied naval forces.

Outbreak of World War I

When World War I began in August 1914, the Ottoman Empire initially remained neutral. However, German diplomatic pressure and naval presence in the region gradually pulled the Ottomans toward the Central Powers.

The Ottoman Empire officially entered the war on October 29, 1914, after Turkish warships bombarded Russian ports in the Black Sea. This action effectively closed the Dardanelles to Allied shipping.

Russia, now cut off from its allies, faced severe supply shortages. Britain and France recognized that opening the strait would both relieve their Russian ally and potentially knock the Ottoman Empire out of the war.

By early 1915, Allied military planners developed the Dardanelles strategy as a way to break the stalemate on the Western Front and create a new theater of operations. This decision would lead to the ill-fated campaign beginning in February 1915.

Origins of the Campaign

The Dardanelles Campaign emerged from a complex mix of strategic needs and political calculations. Britain and its allies sought a way to break the stalemate on the Western Front while also creating a sea route to Russia through Ottoman territory.

Allied Strategic Objectives

The origins of the Dardanelles Campaign can be traced to late 1914 when the Allied powers faced a deadlock on the Western Front. Britain’s First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, became a strong advocate for finding an alternative approach to defeat Germany and its allies.

The campaign aimed to knock Turkey out of the war by capturing Constantinople (now Istanbul). This would open a supply route to Russia through the Black Sea and potentially bring neutral Balkan states into the war on the Allied side.

British military planners believed Turkey was the “soft underbelly” of the Central Powers. They assumed Ottoman forces were weak and could be easily overcome, which later proved to be a serious miscalculation.

Naval Strategy Formation

The naval strategy developed in early 1915 focused on forcing passage through the Dardanelles strait using only warships. Churchill was particularly enthusiastic about this approach, believing naval power alone could achieve victory.

On February 19, 1915, British and French ships began bombardment of Ottoman forts guarding the Dardanelles. The plan relied on battleships to silence Turkish defenses along the narrow waterway and sweep mines that blocked the passage.

Military leaders disagreed about the approach. Some insisted troops would be needed from the start, while naval commanders believed warships could succeed independently. This tension in strategy would prove problematic as the campaign progressed.

The planning was hasty and based on insufficient intelligence about Turkish defenses. Critically, Allied leaders underestimated both Ottoman military capabilities and the determination of Turkish forces to defend their homeland.

Primary Military Operations

The Dardanelles Campaign was defined by three main phases of military action. These operations began with naval bombardments, followed by amphibious landings and subsequent ground battles across the Gallipoli Peninsula.

Initial Naval Assault

The naval operations against the Ottoman Empire began on February 17, 1915, when Allied warships bombarded Turkish forts at the entrance to the Dardanelles Straits. On March 18, a major Allied fleet of 18 battleships attempted to force passage through the straits toward Constantinople.

This assault failed dramatically when Turkish mines sank three battleships (HMS Irresistible, HMS Ocean, and the French Bouvet) and damaged three others. Minesweepers, mostly civilian trawlers with inexperienced crews, proved ineffective against the current and enemy fire.

The naval commanders grew hesitant after these losses, leading to the decision that naval power alone couldn’t break through the defenses. This failure prompted military leaders to develop plans for a land invasion to capture the Gallipoli Peninsula.

Landings at Gallipoli

On April 25, 1915, Allied forces launched amphibious landings at multiple locations across the Gallipoli Peninsula. British troops landed at Cape Helles on the peninsula’s southern tip, while the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) forces landed further north at what became known as Anzac Cove.

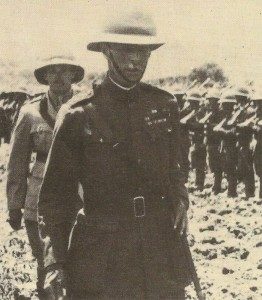

The landings faced immediate difficulties. At Anzac Cove, troops landed about a mile north of their intended position, facing steep cliffs and strong Turkish resistance led by Mustafa Kemal (later Atatürk). The terrain proved challenging, with narrow beaches giving way to rugged hills.

At Cape Helles, British forces established beachheads but suffered heavy casualties. The element of surprise was lost as Ottoman forces had been given time to strengthen their defenses during the weeks following the naval assault.

Significant Battles and Offensives

Several major battles characterized the campaign after the initial landings. In August 1915, Allied forces launched a new offensive with fresh troops landing at Suvla Bay, just north of Anzac Cove. This operation aimed to break the stalemate but quickly bogged down due to indecisive leadership.

Concurrent with the Suvla landings, ANZAC forces attempted to seize the high ground at Lone Pine and Chunuk Bair. The Battle of Lone Pine (August 6-10) saw Australian forces capture Turkish trenches in brutal hand-to-hand combat. The New Zealanders briefly captured Chunuk Bair but couldn’t hold it against Turkish counterattacks.

These August offensives represented the last major Allied attempt to break through. By October, the campaign’s failure was becoming apparent. Worsening weather conditions, disease, and dwindling supplies further hampered operations, leading to the eventual evacuation of all Allied forces by January 1916.

Key Figures and Forces Involved

The Dardanelles Campaign brought together military leaders and forces from multiple nations in a complex operation. Various military units with different capabilities and backgrounds faced challenging conditions during this 1915 campaign.

Leadership and Command

Winston Churchill, as First Lord of the Admiralty, strongly advocated for the Dardanelles operation. He believed a naval attack could force open the straits and reach Constantinople, providing a decisive blow against the Ottoman Empire.

Lord Kitchener, British Secretary of State for War, initially supported a naval-only operation but later authorized land forces when naval efforts stalled. He faced criticism for underestimating the required troop numbers.

Sir Ian Hamilton was appointed commander of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force in March 1915. Despite his experience, Hamilton struggled with inadequate preparation time and limited resources.

On the Ottoman side, German General Liman von Sanders provided crucial leadership. His strategic placement of Turkish forces along likely landing sites proved decisive in containing the Allied advances.

Composition of Allied Forces

The Allied forces included diverse units from across the British Empire and France. The British 29th Division formed the core of the landing force at Cape Helles.

The ANZAC (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) troops played a central role, landing at what became known as ANZAC Cove. These forces included the Australian Light Horse regiments, though they fought as infantry rather than mounted troops.

The French Oriental Expeditionary Corps participated in operations primarily on the Asian side of the Dardanelles. Their colonial troops brought experience from various campaigns.

The 29th Indian Brigade, including Gurkha troops, provided valuable support throughout the campaign. Their mountain warfare skills proved useful in the difficult terrain.

The Royal Naval Division, composed of naval personnel serving as infantry, also participated in land operations after initial naval assaults failed.

Ottoman Army and Defenses

The Turkish forces defending the Dardanelles were more prepared than Allied commanders expected. The Ottoman Empire had modernized its military with German assistance before the war.

Turkish artillery positions commanded the narrows with well-placed guns on both the European and Asian shores. These defenses were supplemented by sea mines that damaged or sunk several Allied ships during the March 18 naval assault.

The Ottoman 5th Army, commanded by Liman von Sanders, effectively distributed its forces to counter Allied landings. Turkish troops demonstrated remarkable resilience and determination despite equipment shortages.

Young Turkish officers like Mustafa Kemal (later Atatürk) showed exceptional leadership, holding critical defensive positions against ANZAC forces. His famous order to his troops—”I don’t order you to attack, I order you to die”—reflected the determination of Ottoman defenders.

Naval Engagements and Challenges

The naval operations in the Dardanelles Campaign represented one of the most ambitious naval efforts of World War I. Allied forces faced formidable defenses as they attempted to gain control of this strategically crucial waterway.

Attempt to Control the Dardanelles

The Allied naval offensive began on February 17, 1915, with a fleet comprising British and French battleships. The super-dreadnought HMS Queen Elizabeth was the pride of this fleet, with its modern design and powerful 15-inch guns.

Initial attacks focused on destroying the outer forts guarding the entrance to the straits. While these bombardments achieved some success, the results fell short of expectations. Many guns remained operational despite heavy shelling.

On March 18, a major assault was launched with 18 battleships attempting to force the strait. This attack ended in disaster. The French battleship Bouvet struck a mine and sank in just three minutes with the loss of over 600 sailors.

Two British battleships, HMS Irresistible and HMS Ocean, were also lost to mines that day. The Allied fleet was forced to withdraw after losing three battleships and suffering damage to others.

Use of Mines and Forts

The Ottoman defense of the Dardanelles relied heavily on an integrated system of minefields and shore batteries. Naval mines proved to be the most effective weapon against the Allied fleet.

The Ottomans had placed ten lines of mines across the narrowest part of the strait, containing about 370 mines in total. Allied minesweepers, mainly converted fishing trawlers with civilian crews, struggled to clear these deadly obstacles.

Shore batteries were positioned to fire directly at minesweepers, making mine-clearing operations extremely dangerous. When larger battleships attempted to suppress these guns, they had to maneuver in waters filled with mines.

The Germans provided technical assistance to the Ottomans, particularly in organizing the minefield defenses. Mobile howitzer batteries were also cleverly concealed along the shores, allowing them to fire and then quickly change position before Allied ships could effectively target them.

International Involvement

The Dardanelles Campaign drew military forces from across the British Empire and its allies. Several nations committed significant troops and resources to this ultimately unsuccessful operation against the Ottoman Empire.

Roles of Australia and New Zealand

Australia and New Zealand made their first major military contribution as independent dominions during the Dardanelles Campaign. Together their forces formed the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC), which landed at what became known as Anzac Cove on April 25, 1915.

The ANZACs faced steep cliffs and determined Turkish resistance immediately upon landing. These troops, commanded by Lieutenant-General William Birdwood, were part of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force.

Around 50,000 Australians and 16,000 New Zealanders served at Gallipoli. They suffered heavily with approximately 8,700 Australians and 2,700 New Zealanders killed during the campaign.

This baptism of fire helped forge national identities for both countries. April 25 is now commemorated as Anzac Day, one of the most significant national holidays in both Australia and New Zealand.

French Participation

French forces made a substantial contribution to the Dardanelles Campaign, though their role is often overshadowed in English-language accounts. The French deployed approximately 79,000 troops as part of the Corps Expéditionnaire d’Orient.

French troops landed at Kum Kale on the Asian side of the Dardanelles on April 25, 1915. This diversionary attack helped protect the main Allied landings at Cape Helles.

After securing their objectives, French forces joined British units on the Gallipoli peninsula. They primarily operated on the right flank of the Allied line at Cape Helles.

The French suffered around 27,000 casualties before withdrawing in January 1916 alongside other Allied forces. Their naval forces also participated significantly in the failed naval attacks on the Dardanelles in March 1915, losing several battleships to mines.

End of the Campaign

The Dardanelles Campaign ended with a complete Allied withdrawal from the Gallipoli Peninsula, marking one of the most successful retreats in military history despite the overall failure of the offensive.

Evacuation of Allied Troops

The evacuation of Allied forces began in December 1915 after months of stalemate and mounting casualties. High-ranking officials finally acknowledged that the campaign could not achieve its objectives. The evacuation was conducted in stages, with troops first withdrawing from Suvla Bay and ANZAC Cove in December 1915.

Unlike the landings, the evacuation was meticulously planned and executed with remarkable efficiency. British commanders used ingenious deception tactics to hide their intentions from Turkish forces, including self-firing rifles triggered by water dripping into tin cans.

The final evacuation from Cape Helles was completed by January 9, 1916. In total, about 140,000 men were successfully withdrawn with minimal casualties – a stark contrast to the campaign’s earlier phases.

The evacuation represents the only truly successful part of the Gallipoli Campaign, which otherwise cost the Allies around 250,000 casualties without achieving any strategic objectives.

Aftermath and Historical Impact

The Dardanelles Campaign resulted in devastating human losses and far-reaching political consequences that reshaped military strategy and altered national trajectories. Its failure triggered leadership changes and prompted strategic reassessments across the Allied forces.

Casualties and Losses

The human cost of the Dardanelles Campaign was staggering. Allied forces suffered over 220,000 casualties out of approximately 500,000 troops deployed. British, French, Australian, and New Zealand forces bore heavy losses during the eight-month campaign.

Ottoman forces, though defending their territory with fewer resources, endured approximately 250,000 casualties. Disease compounded battlefield injuries, with dysentery and other illnesses claiming numerous lives in the harsh Gallipoli conditions.

For Australia and New Zealand, the campaign was particularly significant. Around 8,000 Australian soldiers and 2,700 New Zealanders died, creating a profound national trauma that later became central to their national identities.

Many soldiers who survived faced lifelong physical disabilities and psychological trauma. Those returning home confronted the challenge of reintegration into civilian society while dealing with their wartime experiences.

Consequences and Legacy

The campaign’s failure triggered immediate political repercussions. Winston Churchill, who strongly advocated for the operation, resigned from his position as First Lord of the Admiralty. The disaster tarnished his reputation for years.

In Britain, the campaign’s failure contributed to reshuffling the government and military leadership. Public confidence in political and military decision-making was severely undermined.

For Australia and New Zealand, the Gallipoli campaign fostered a growing sense of national identity separate from British imperial ties. April 25, the landing date at Gallipoli, became commemorated as ANZAC Day.

In Turkey, the successful defense bolstered Turkish nationalism. Military leader Mustafa Kemal (later Atatürk) rose to prominence during the campaign and eventually became the founder of modern Turkey.

Re-evaluation of Strategy

The Dardanelles disaster prompted Allied powers to critically reassess amphibious operations. Military planners recognized the need for better reconnaissance, improved coordination between naval and land forces, and more realistic objectives.

The campaign exposed serious flaws in intelligence gathering and operational planning. Allied forces had underestimated Ottoman defensive capabilities and failed to anticipate the challenges of the terrain.

Naval strategy underwent significant revision after multiple battleships were lost to mines in the strait. The limitations of naval power against land fortifications became painfully clear.

The failure reinforced the dominant Western Front strategy among British military leadership. Resources were redirected to France and Belgium, with peripheral campaigns receiving less support thereafter.

Military historians later identified the campaign as a textbook example of how political objectives can overtake military realities. The Dardanelles campaign remains studied in military academies as a case study in the importance of thorough planning and realistic assessment of objectives.

Frequently Asked Questions

The Dardanelles Campaign stands as one of World War I’s most analyzed military operations, marked by complex strategic decisions, challenging terrain, and significant casualties. Key elements include the naval assault, the Gallipoli landings, and the lasting impact on nations like Australia, New Zealand, and Turkey.

What were the primary objectives of the Allied powers in initiating the Dardanelles Campaign?

The Allied powers launched the Dardanelles Campaign in 1915 with several strategic objectives. They aimed to force open the 38-mile-long Dardanelles strait to gain access to the Sea of Marmara and Constantinople (Istanbul).

By capturing Constantinople, the Allies hoped to knock the Ottoman Empire out of the war. This would secure a supply route to Russia through the Black Sea, bolstering the struggling Eastern Front.

The campaign also sought to divert Ottoman forces from fighting against Russia and potentially bring neutral Balkan states into the war on the Allied side.

Which military leaders were pivotal during the Dardanelles Campaign, and what strategies did they employ?

First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill championed the Dardanelles operation as a way to break the stalemate on the Western Front. His strategy focused initially on a purely naval approach to force the strait.

Admiral Sackville Carden developed the original naval plan, later replaced by Admiral John de Robeck who commanded the naval assault on March 18, 1915. They employed a strategy of using battleships to silence Turkish forts.

General Sir Ian Hamilton led the land campaign at Gallipoli, attempting to capture the heights overlooking the strait. His strategy involved multiple landing points but suffered from poor intelligence and inadequate resources.

Turkish commander Mustafa Kemal (later Atatürk) brilliantly positioned his forces on the ridges above the landing beaches. His defensive strategy emphasized holding the high ground at all costs.

What were the major consequences and historical significance of the Dardanelles Campaign for the involved nations?

The campaign resulted in approximately 250,000 casualties on each side, marking it as one of the bloodiest of World War I. It represented a significant Allied failure that extended the war.

For Turkey, the victory boosted national pride and contributed to the rise of Mustafa Kemal, who later founded modern Turkey. The successful defense helped establish Turkish national identity.

Australia and New Zealand experienced a profound awakening of national consciousness. The campaign helped forge their distinct national identities separate from Britain.

In Britain, the failure led to political consequences including Churchill’s resignation from the Admiralty. It also prompted a reevaluation of military strategy and leadership.

How did the terrain and conditions at Gallipoli affect the outcome of the Dardanelles Campaign?

The Gallipoli Peninsula featured steep cliffs, narrow beaches, and rugged ridges that heavily favored the defenders. Turkish forces held the high ground, allowing them to rain fire down on the exposed Allied troops.

Extreme weather conditions plagued the campaign, with scorching summer heat followed by freezing winter conditions. Soldiers suffered from heatstroke, frostbite, and trench foot.

Disease became a major killer, with dysentery and other illnesses spreading rapidly due to poor sanitation, limited fresh water, and swarms of flies. More men were evacuated for illness than for wounds.

The confined landing areas created bottlenecks that prevented rapid deployment of troops and supplies. This allowed Turkish defenders time to reinforce positions and establish effective defensive lines.

In what ways did naval warfare contribute to the progression of the Dardanelles Campaign?

The campaign began as a purely naval operation on February 19, 1915, with British and French ships bombarding Turkish forts along the strait. The aim was to clear the waterway of mines and coastal defenses.

The naval assault culminated in a decisive setback on March 18, when three battleships were sunk by mines and several others damaged. This failure led to the decision to launch a land campaign.

Naval forces provided crucial fire support for ground troops during and after the landings. Battleships used their heavy guns to target Turkish positions, though with limited accuracy.

Ships also facilitated the eventual successful evacuation of Allied forces in December 1915 and January 1916, which historians consider the most successful aspect of the entire campaign.

What role did the Anzac forces play in the Dardanelles Campaign, and what legacy did it leave in their home countries?

Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (Anzac) troops landed at what became known as Anzac Cove on April 25, 1915. They were tasked with securing the central section of the peninsula.

Anzac soldiers faced immediate difficulties, landing on a narrow beach beneath steep cliffs where Turkish defenders held dominant positions. Despite this, they established a tenuous foothold.

The “Anzac spirit” of courage, endurance, and mateship emerged during the campaign. These qualities became central to Australian and New Zealand national identity and continue to be celebrated.

April 25 is now commemorated as Anzac Day in Australia and New Zealand, marking the anniversary of the Gallipoli landings. It has become their most significant national day of remembrance.

References and literature

Illustrierte Geschichte des Ersten Weltkriegs (Christian Zentner)

History of World War I (AJP Taylos, S.L. Mayer)

Der Erste Weltkrieg – Storia illustrata della Prima Guerra Mondiale (Hans Kaiser)

Der I. Weltkrieg – Eine Chronik (Ian Westwell)