The monthly days of 1915:

- January 1915

- February 1915

- March 1915

- April 1915

- May 1915

- June 1915

- July 1915

- August 1915

- September 1915

- October 1915

- November 1915

- December 1915

The situation at the fronts in 1915:

On 21 May 1915, a headline in the Daily Mail screamed ‘The Tragedy of the Shells’. The paper asserted that Kitchener ‘had starved the army in France of high explosive shells’. Kitchener claimed (perhaps with some justice) that his comments had been misinterpreted by Asquith. Be that as it may, drastic action was obviously called for. On 26 May, the British Government announced the creation of a Ministry of Munitions with wide powers, to be headed by David Lloyd George. The Ministry began to function on 2 July 1915 and quickly achieved dramatic results. Four months later an inter-allied munitions organization was established by Lloyd George and his equally dynamic French counterpart, Albert Thomas. In spring 1916, Kitchener attempted to persuade a brilliant engineer, Herbert Hoover (later US President) to renounce his American citizenship and join the Ministry of Munitions as Lloyd George’s eventual successor. Nothing had been settled when Kitchener was drowned and Lloyd George took over the War Office (June 1916).

Kitchener had seen, with unusual clarity, that the war would last for at least three years and that Germany ‘will only give in when she is beaten to the ground’. He laid detailed plans for a ‘New Army’ of 70 divisions (1.2 million men) by 1917; all would-be volunteers unconnected with the Territorial system. As a young volunteer in the Franco-Prussian War, Kitchener had noted with disgust how the French Territorials had decamped en masse from the hastily improvised Prussian Army of the Loire.

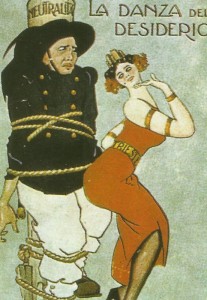

French left the BEF in December 1915 and was succeeded by Haig. A bitter argument over Allied grand strategy was now in full swing. Haig and the new Chief of Imperial General Staff, Robertson, belonged to the so-called ‘Westerner’ faction, which advocated total concentration of all fighting men and guns in France. The opposing ‘Easterners’ (including Lloyd George and Churchill) advocated decisive action against the weaker brethren among the Central Powers; Austria, Italy (the latter entered the war on the Allied side in May 1915) and Ottoman Turkey.

Denied large-scale supplies of Allied munitions, the Russians had to endure from April successive crushing German offensives in the south (Mackensen) and in the west (Hindenburg) supported by overwhelming concentrations of heavy artillery. All Russian Poland, including Warsaw (4 August), was overrun by the Germans. The Eastern Front did not stabilize until late September 300 miles (ca. 483 km) to the east by which time the Tsar’s armies had sustained over 2 million casualties, half of them prisoners, with the loss of nearly 3,000 guns. The Tsar himself had felt impelled to replace his uncle Grand Duke Nicholas as C-in-C (5 September) thus further divorcing himself from the vital events on the home front. No wonder Falkenhayn, the German Chief of Staff, felt he had achieved his spring aim of ‘the indefinite crippling of Russia’s offensive strength’. He withdrew victorious divisions across the Central Powers’ superb railway network to strike down Serbia which had ferociously resisted her Austrian attackers for over a year. In a little over six weeks (October-November), Mackensen’s veterans, aided by Bulgaria’s stab-in-the-back intervention, had overrun Serbia leaving her armies to make a memorable winter retreat to Albania and the sea. Franco-British landings at Salonika (Northern Greece) were too little and too late to affect the outcome.

Falkenhayn felt he was now free to pursue his most cherished strategic aim to wear down the already sorely-tried French Army so that ‘breaking point would be reached and England’s best sword knocked out of her hand’ (December). The Entente should collapse before the new Kitchener armies could exert their million-strong pressure on the Western Front.

Only in remote African theaters did the Allies score clear-cut 1915 military successes. Anglo-French colonial forces completed the hard-won conquest of the Cameroons (October 1915-February 1916) after Botha’s South Africans had triumphantly overrun German South-West Africa (February-July 1915) in a model campaign of desert logistics and Boer-mounted commando advances. Imperial forces were now available to invade German East Africa after a year on the defensive.