The Army of Portugal in World War One (1916-1918).

Uniforms, strength and organization of the Portuguese Army in Europe and Africa, 1916 – 1918.

Army of Portugal in World War One (1916-1918)

Table of Contents

Portugal joined World War One on the Allied side in March 1916. Prior to being transported to France, the Portuguese Expeditionary Force undergone exercising and outfitting in Sussex, UK.

Overview

The Portuguese Army in World War I played a not unsignificant, though often overlooked, role in the conflict, particularly on the Western Front.

Background

Portugal entered World War I on the side of the Allies in March 1916, following a series of diplomatic incidents with Germany, including the seizure of German ships in Portuguese ports. Portugal’s main motivations included maintaining its colonial possessions in Africa, honoring its alliance with Britain, and asserting itself internationally.

Main Contributions

Portuguese Expeditionary Corps (CEP):

– Size: About 55,000 men.

– Deployment: Sent to the Western Front in France in early 1917.

– Sector: Assigned to a sector of the front near the Lys River (northern France, near Flanders).

– Role: The CEP was integrated into the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and was responsible for holding a section of the front line.

African Theatres:

– Portuguese colonial troops also fought in Africa, especially in Angola and Mozambique, against German colonial forces.

Key Engagements

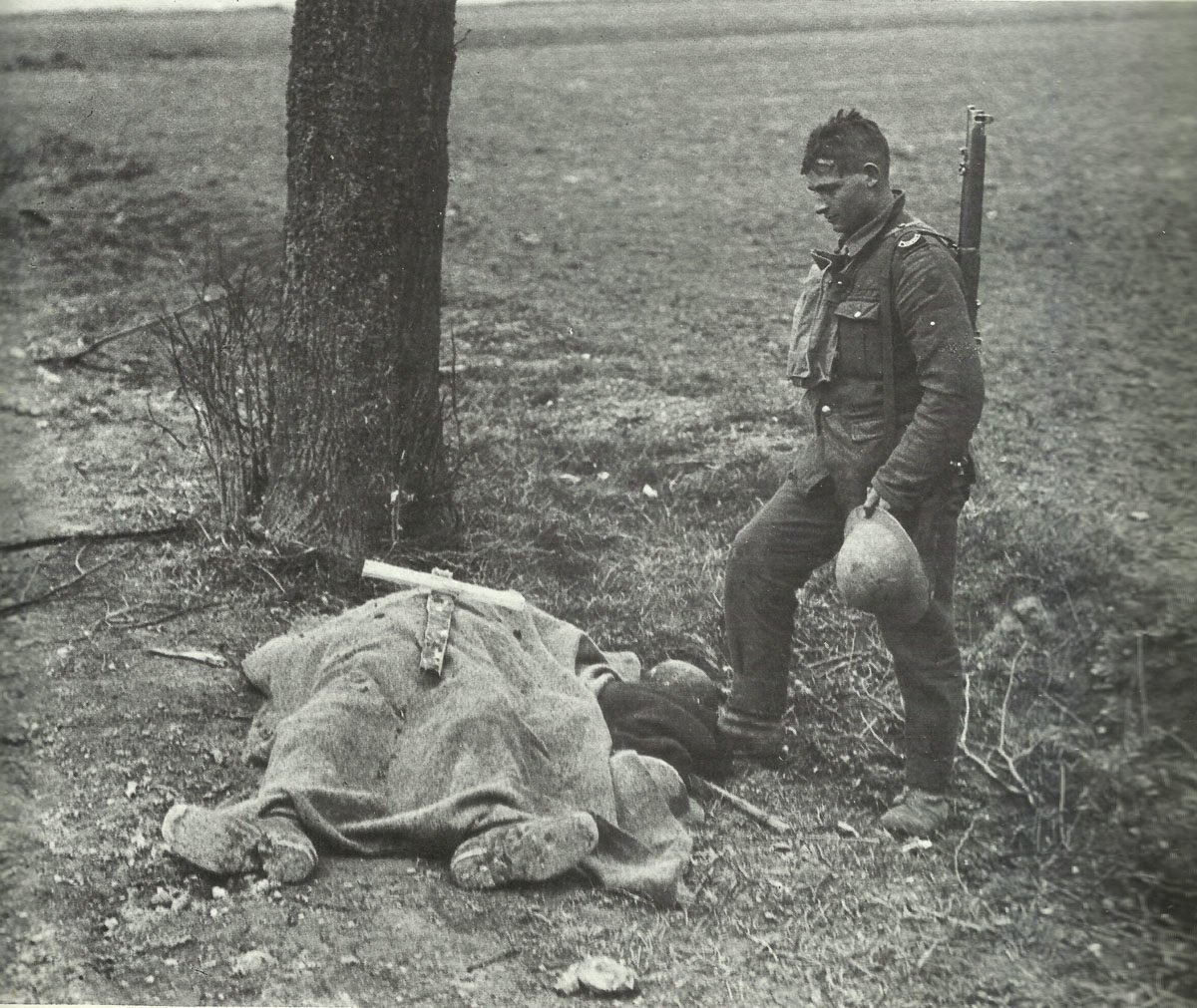

Battle of La Lys (9 April 1918):

– The most significant engagement involving Portuguese forces.

– The CEP, weakened by exhaustion, poor supplies, and low morale, faced a massive German offensive (Operation Georgette).

– The Portuguese lines were overrun, suffering heavy casualties: about 400 killed, 6,500 captured, and many wounded.

– Despite this setback, the Portuguese soldiers’ resistance delayed the German advance, allowing British forces to reinforce the sector.

Challenges

– Logistical issues: The Portuguese Army suffered from inadequate equipment, poor supplies, and insufficient training.

– Morale: Harsh conditions, long periods in the trenches, and political instability at home affected morale.

– Political instability: Portugal was undergoing political turmoil, including a military coup in December 1917.

Legacy

– The Portuguese Army’s participation, while marked by difficulties and heavy losses, demonstrated Portugal’s commitment to the Allied cause.

– The experience had a significant impact on Portuguese society and politics, contributing to instability in the post-war years.

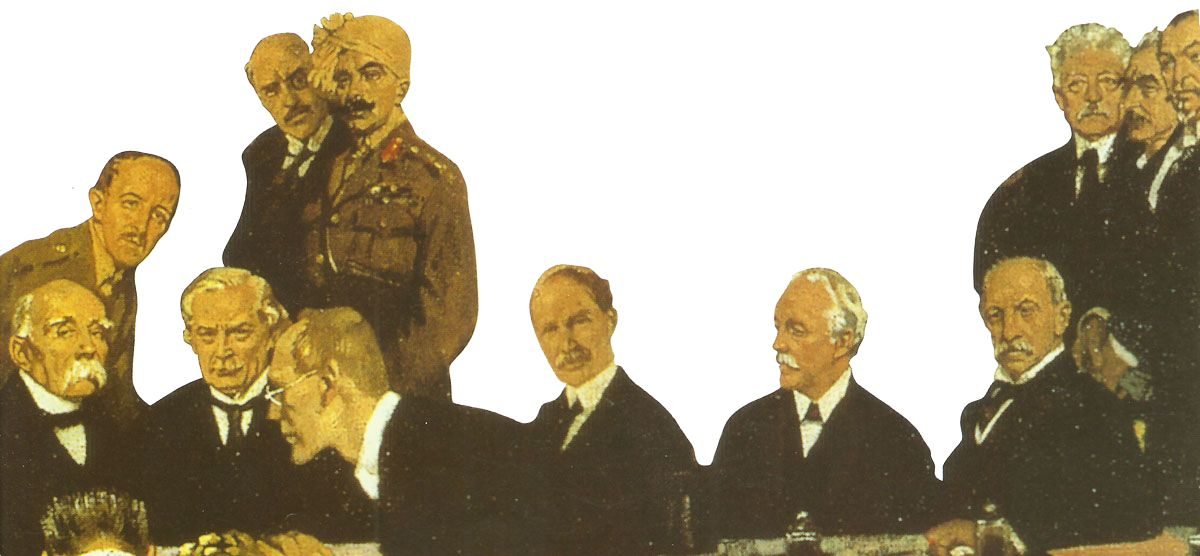

Portuguese Uniforms

The shade of the field uniform looked like the French horizon azure. It was made up of a single-breasted tunic with stand collar and fly-front. It had parallel pleated patch breast pockets along with pointed flap and button, however no side pockets. The shoulder straps were created of the identical components, and there had been a pair of buttons at the rear of each cuff. The tunic had been used with harmonizing pantaloons and puttees. The greatcoat was double-breasted having huge fall collar and half-belt fastening at the rear with a pair of buttons.

Officers dressed in a single-breasted greatcoat with half a dozen buttons at the front, pleated patch breast pockets, and dipping side pockets, all with buttoned flap. It had a solitary button on the cuffs, which could be fixed around the wrist using a strap. Officers furthermore dressed in an extended gray cloak with dark-blue velvet collar, and pointed gray cloth collar patches on which were placed the badges of rank.

The peaked service cap had a harmonizing cloth-covered peak with strip of silver braid for officers and normal shaded leather (silver lace for officers) chin strap, and the arm-of-service banner was placed on the front. The fluted steel helmet had been considered to have been produced under agreement in Birmingham, Great Britain.

Officers were known to use the identical fundamental uniform as their soldiers, however some did dress in open tunics with gray shirts and black ties, while some dressed in tunics with big ‘bellow’ side pockets. Harmonizing breeches were used with brown leather field footwear, or ankle boots with leather gaiters. Officers dressed in the ‘Sam Browne’, while other ranks gotten the Portuguese kind of the British 1908-pattern web equipment.

Rank was showed on the cuffs of the tunic and greatcoat, as well as on the cloak collar of officers, while other ranks used their rank badges on the shoulder straps.

Arm-of-service was shown by an oxidized (blackened) metal, or silver-embroidered badge which was placed on the front of the peaked cap as well as on the collar. Several badges and regimental numbers were stitched in dark blue and displayed on the upper sleeve on each arm.

Portuguese Forces on March 9, 1916:

Over 12,000 regular troops (4,300 including 2,800 African in Mozambique).

Portuguese strength on the Western Front on November 11, 1918:

35,000 soldiers (in 2 divisions) with 768 motor vehicles.

Portuguese Army in East Africa

The third and larger expedition arrived in July 1916. This was made up of the third battalions of Regimentos de Infantaria Nos.23, 24 and 28 plus two reinforcing companies for No.21; three more machine gun groups (Nos 4, 5 & 8); five artillery groups (Nos. 1 and 2 plus three more from the Mountain Artillery Regiment); and engineer, medical and service units.

The Portuguese also took steps to expand their Askari units. Those involved in the crossing of the Rovuma included the Guardia Republicana, a number of Companhias Indigenas Expeditionarias (notably Nos. 17 and 19 to 24), and the Nyassa Company‘s 1a Companhia.

The European battalions provided the main mass, but Askaris accompanied them, and they were screened by a ‘black column’ consisting of a European mounted infantry company and four African companies. Some Portuguese troopers from Cavalaria No.3 formed part of the advance towards Nevala, but little was heard of this arm thereafter.

The Askaris suffered more battle casualties than the Europeans, but the latter’ losses from disease were ten times those of the Africans. Apart from Captain Curado’s 21a Companhia Indigena, which showed what the Askaris could do with good leadership, the Portuguese demonstrated that they were no match for the Germans. Indeed, the German conclusion was that 500 German troops could safely take the offensive against 1,500 Portuguese.

Portuguese losses in East Africa 1916-18:

4,723 men (from 30,701 troops employed), 4 guns, 18 machine-guns.

PORTUGAL (March 9, 1916 – November 11, 1918)

- Soldiers available on mobilization = 12,000+

- Army strength during the war = 100,000

- KIA Military = 8,145

- Wounded Military = 14,784

- Civilian losses = unknown, but low

References and literature

Army Uniforms of World War I (Andrew Mollo, Pierre Turner)

Armies in East Africa 1914-18 (Peter Abbott)

Portugal 1914-1926: From the First World War to Military Dictatorship (Filipe Ribeiro de Meneses)