The German attack on the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941 – The beginning of the operation with the code-name ‘Barbarossa’

On June 22, 1941, the German Wehrmacht began the largest invasion in the history of war under the code-name of ‘Unternehmen Barbarossa’. Operation Barbarossa has not even close to any comparison in military history in the size of the deployed troops, speed of execution of operations or geographical extent of the battlefield.

The goal of the Wehrmacht was nothing less than the complete defeat of the Soviet Union, a nation which at the time had the largest army and air force in the world.

The actual Operation Barbarossa took place from June 22, 1941, until the Red Army’s counteroffensive before Moscow – in early December 1941. It was during this period that the Soviet colossus came closest to defeat, which was probably the only time when Nazi Germany could have won World War II on its own. And since the end of World War II, there has been an uninterrupted, heated debate about the operational and strategic decisions of the German and Soviet high commands that led to the known outcome, especially for the extremely critical period from July to September 1941.

With the invasion of the Soviet Union by Germany and its allies in the summer of 1941, the war changed in several ways. One change, which was not clear to everyone at the time but was true in retrospect, was that from now until the end of the war in Europe in May 1945, the focus of the fighting shifted to the new Eastern Front. More people fought and died there than on all other World War II fronts worldwide combined. This was due to the nature of the warfare there, which made it quite unlikely that the opponents could return to a peaceful relationship, and the ability of Germany’s opponents to stay together until victory.

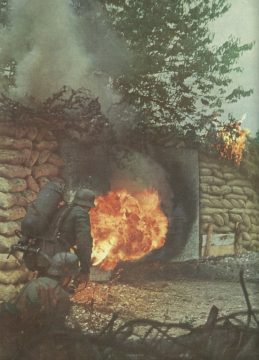

The attack on the Soviet Union in the early morning hours of June 22, 1941, was completely unexpected. Although Red Army units at some sections of the border did receive last-minute warnings, the general orders were not to open fire in case this was merely a German provocation.

The German Luftwaffe, which deployed 2,700 aircraft, about 60 percent of its total strength, flew carefully planned attacks in the morning, destroying much of the Red Air Force on the ground, rendering forward airfields useless, and shooting down most of the Soviet aircraft that nevertheless made it into the air. This resulted in almost complete German air supremacy, which lasted only the first few months but had a major impact on the rapid advance of German ground forces during this period.

Even in the far north, German mountain divisions attacked across the Finnish-Soviet border, hoping to capture Murmansk and the Kola Peninsula. Along the rest of the Finnish border, the Finnish Army attacked a few days later, along with some German units sent in support. The objective of these attacks was to cut the important Murmansk Railway, and advance along both sides of Lake Ladoga toward Leningrad to cut off the city.

To the far south of the long land front was the German 11th Army, along with the Romanian 3rd and 4th Armies, which were soon to attack across the Prut River from Romania into Bessarabia.

The main attack, however, took place on June 22 by the three German Army Groups North, Central, and South. In the first few days, Army Group North and its three armies struck out into the Baltic, overrunning Lithuania in a few days, crossing the Daugava River at several points, and already dominating most of Latvia by the end of the first week of July.

In the central section, which ran essentially south of the former border of the Baltic States to the Pripjet Marshes, Army Group Center with its four armies smashed the opposing Red Army formations and within the first two weeks conquered the eastern part of Poland, which had been annexed by the Soviet Union in 1939.

Finally, Army Group South, with its three armies plus the still somewhat waiting 11th Army in Romania, attacked through the southern part of eastern Poland and reached the territory of the Ukrainian People’s Republic of 1939.

The heavy blows suffered by the Soviet Union were not so much the rapid advances and the loss of such large areas, but much more that so many of the large Soviet front line units were trapped by rapidly advancing armored units and destroyed by the following, experienced German infantry.

The German plan was to destroy as many Red Army units as possible while still in the border areas. It was hoped that such catastrophic initial losses would shake and collapse the structure of the Soviet system of rule. In no case was it to be a long campaign in which the Russian armies would have to be pushed back slowly and frontally, piece by piece, over hundreds or even thousands of miles.

To some extent, the German concept worked in the central section of the front, where two encirclement battles alone captured over 300,000 Russian soldiers. In the south and north, however, Russian troops were driven back rather than encircled, although their losses in dead and wounded, matériel, equipment, and vehicles were enormous.

These dramatic victories immediately led the German leadership to believe that they had already achieved what they had set out to do: To have destroyed Russian military power with one hard blow.

On July 3, 1941, Chief of General Staff Franz Halder wrote in his diary: ‘On the whole, it can be said that the mission of destroying the mass of the Russian army before the Daugava and the Dnieper is accomplished … It is probably not too much to say that the campaign against Russia was won in two weeks.’ On the same day, he responded to congratulations on his birthday on June 30, 1941, with the comments that ‘the Russians had lost the war in the first eight days.’

The impression of victory was further reinforced in the first two weeks of July. In further, large-scale encirclement battles, Army Group Center, now consisting of as many as five armies, advanced into central Russia, taking another 300,000 prisoners of war and occupying the cities of Yelnya and Smolensk on the road to Moscow.

At the same time, Army Group North penetrated into Estonia and reached the outer defenses of Leningrad, while Army Group South advanced toward Kiev and the important industrial and agricultural areas in the Dnieper arc.

The impression was created for the German leadership that only a little mopping up was needed and then everything would be done. However, the situation did not look so rosy for the German soldiers on the Eastern Front, who continued to face the brave and energetic resistance will of the Red Army soldiers and kept encountering new, fresh formations, while their own vehicles and equipment wore out and their losses increased. But Hitler‘s circles still believed that everything was going well.

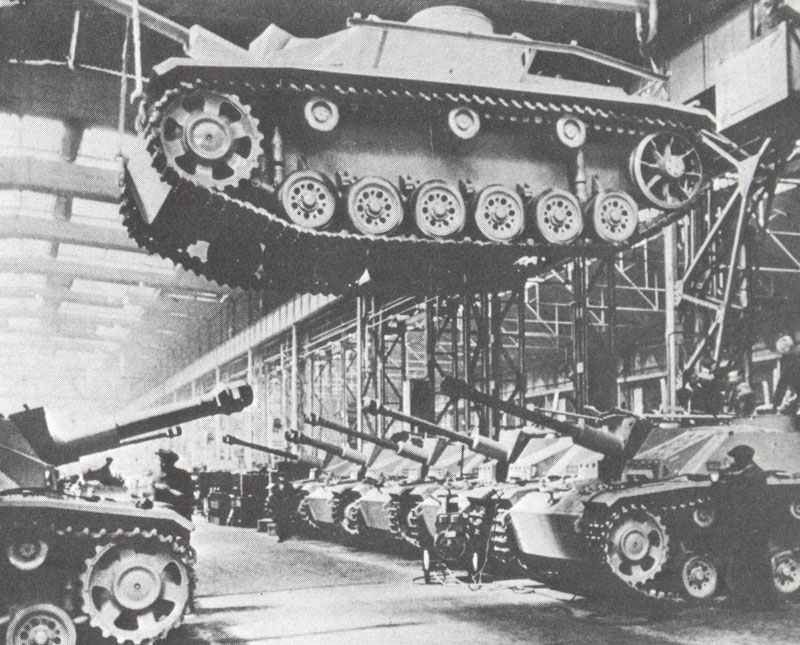

The entire planning of the German offensive was based on the fact that this would be only a short campaign. There were no replacements, nor had any been planned – neither for the losses in soldiers nor in equipment. After all, it was only going to last a few weeks, and no one in leadership was concerned about that.

One of the breathtaking circumstances in the German planning is the complete lack of significant units in reserve. This circumstance will run like a thread through the situation on the Eastern Front from the first day of the Eastern campaign to the day of the surrender in May 1945.

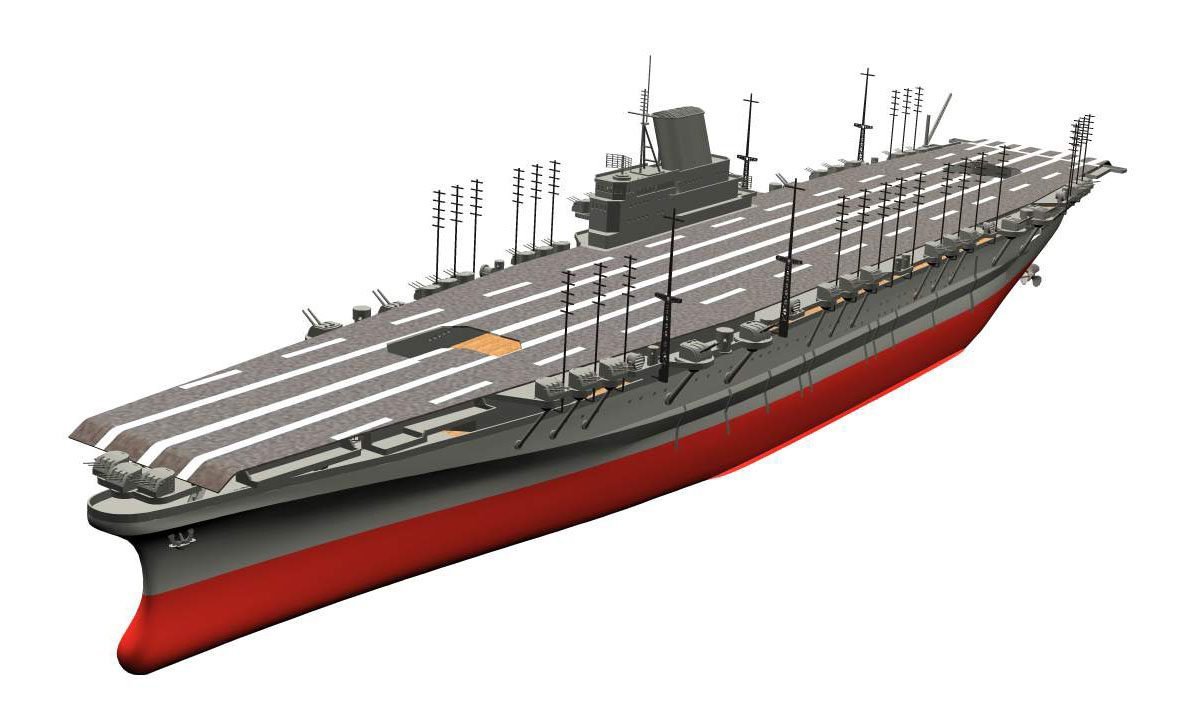

The Luftwaffe assumed that after two months of operations on the Eastern Front it could turn back to the fight with Britain, and all the heavy flak was in the Reich or in the West anyway.

During July, Hitler and many German leaders believed that the risky gamble had paid off.

For a short time it looked as if the war in the East was won and the Germans could do whatever they wanted – in conquered Russia and in the rest of Europe. Therefore, plans were made for the next part of the war against England.

Hitler explained to his staff that the new German eastern frontier would run along the Urals, and wherever a danger stirred behind this line, German units would eliminate it in the east of it.

The mass of the urban population in European Russia was to be reduced by starvation, as were the Soviet prisoners of war. Hitler, his economic experts, and the military agreed on this.

At a conference with Alfred Rosenberg, the new minister for the occupied eastern territories; Hans Lammers, the leader of the Reich Chancellery; Field Marshal Keitel of the OKW; Goering; and Martin Bormann, Hitler declared on July 16, 1941, that the newly won German empire was to be ruthlessly exploited. The local rural population was to have no more rights, except to provide cheap labor. Some smaller parts of the vast conquered country would fall to Germany’s allies, but some of them – Finland, for example – would be absorbed into the coming Greater German Empire anyway.

References and literature

A World at Arms – A Global History of World War II (Gerhard L. Weinberg)

Der Grosse Atlas zum II. Weltkrieg (Peter Young)

Der 2. Weltkrieg (C. Bertelsmann Verlag)

Zweiter Weltkrieg in Bildern (Mathias Färber)

Illustrierte Geschichte des Dritte Reiches (Kurt Zentner)

Unser Jahrhundert im Bild (Bertelsmann Lesering)