The Air War in the Pacific During World War II and the Japanese Flying Ace Saburo Sakai.

Air war in the Pacific from a Japanese perspective

Table of Contents

The air war in the Pacific during World War II was a crucial part of the larger conflict that saw fierce battles over vast ocean expanses and isolated islands. It was a period marked by daring aerial engagements and significant strategic operations. The United States and Japan fought intensely in this arena as each sought control over critical territories and resources. These battles played a decisive role in the course of the war.

One of the notable figures of this period was Saburo Sakai, a celebrated Japanese flying ace. Renowned for his remarkable skill and bravery, Sakai became one of Japan’s most famous pilots. His exploits include engaging in numerous dogfights and surviving serious injuries, including an epic journey back to his base after being wounded. Sakai’s story is emblematic of the broader struggle and the personal stories of heroism and sacrifice that characterized the air war in the Pacific.

Flying above the tropical waters and dense jungles, pilots on both sides engaged in intense combat that tested their limits. The air war in the Pacific highlighted technological innovations and tactical advancements, decisively impacting the larger conflict. As the United States gained momentum, stories of resilience and courage, like that of Saburo Sakai, continued to echo, reminding future generations of the war’s reality and the personal bravery it entailed.

Rise of Japanese Naval Aviation

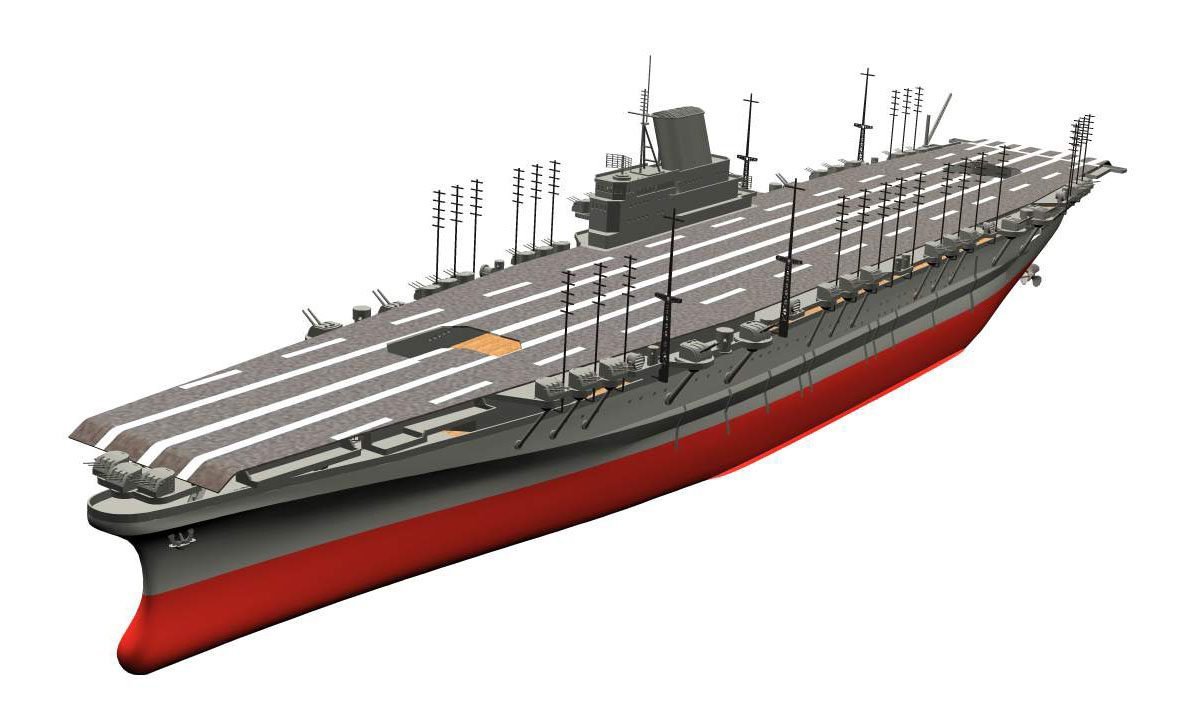

During the early 20th century, the Japanese Navy developed its air capabilities leading up to the Pacific War. Key advancements in aircraft, such as the Mitsubishi A5M and A6M fighters, played a crucial role, and their pilots, or naval aviators, were instrumental in various battles.

The Birth of Mitsubishi A5M and A6M Fighters

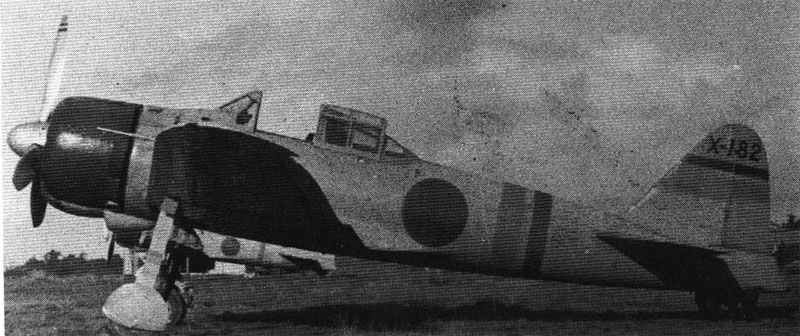

The development of the Mitsubishi A5M, also known as the “Claude,” marked a significant milestone for the Japanese Navy Air Force. First flown in 1935, the A5M was the world’s first all-metal monoplane carrier fighter. Its introduction provided the Imperial Japanese Navy with a rugged and agile aircraft, capable of outmaneuvering many of its contemporaries.

Building on the success of the A5M, the Japanese Navy introduced the Mitsubishi A6M Zero. The Zero, debuting in 1940, quickly gained fame for its exceptional range and agility. It became a symbol of Japanese air power during the early stages of World War II. With advanced features like long-range capabilities and lightweight construction, the A6M Zero allowed pilots to dominate the skies over the Pacific.

The Role of Naval Aviators

Japanese naval aviators were a vital asset to the Imperial Japanese Navy. Trained rigorously, they exhibited exceptional skill and discipline in aerial combat. These pilots operated both the A5M and the renowned A6M Zero fighters from aircraft carriers, providing strategic flexibility and reach.

The aviators’ proficiency enabled effective execution of complex missions, including surprise attacks and defensive maneuvers. Their role extended beyond piloting to include reconnaissance and coordination with naval formations. Naval aviators were pivotal during key operations such as the attack on Pearl Harbor, showcasing their crucial contribution to Japanese naval warfare strategies in the Pacific.

Major Battles and Campaigns

The Pacific air war featured several critical battles that shaped the outcome of World War II. These battles highlighted the strategic importance of air superiority and involved intense confrontations between Allied and Japanese forces.

Assault on Pearl Harbor and its Impact

The attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, marked the United States’ entry into World War II. The Japanese navy launched a surprise aerial assault, targeting the U.S. Pacific Fleet stationed in Hawaii. This attack resulted in significant damage to American battleships and aircraft, crippling naval capabilities.

This bold move by Japan aimed to remove the U.S. as a Pacific power. Eight battleships were targeted, and over 2,400 Americans were killed. The destruction rallied American resolve, leading to a declaration of war against Japan. The attack’s impact was significant, mobilizing the U.S. to expand its military efforts in the Pacific theater, setting the stage for subsequent air and sea battles.

Guadalcanal Campaign: A Turning Point

The Guadalcanal Campaign, from August 1942 to February 1943, was a major turning point. It marked the first major offensive by Allied forces against Japan. Situated in the Solomon Islands, Guadalcanal was key for controlling sea routes between the U.S. and Australia.

Allied forces fought to capture the island and the crucial airfield there. The hard-fought campaign involved intense aerial and ground combat, demonstrating the importance of air superiority. Both sides suffered significant losses, but control of the airfield allowed the Allies to launch further offensives. The battle’s outcome shifted strategic initiative to the Allies, signaling a change in momentum in the Pacific.

Iwo Jima and Philippines Operations

In the final stages of the Pacific War, air operations over Iwo Jima and the Philippines became vital. The Battle of Iwo Jima, from February to March 1945, was intense, with U.S. Marines capturing the island after brutal fighting. Strategically, Iwo Jima was crucial for air operations against Japan, providing a base for fighter escorts and damaged bombers.

In the Philippines, the Allies aimed to liberate the islands from Japanese occupation. The air campaign in the Philippines, including the significant Battle of Leyte Gulf, involved intense combat and was crucial in securing control of the region. Clark Field became a key target, and its capture was instrumental in Allied success. These operations illustrated the decisive nature of air power in the Pacific.

Notable Aircraft and Aerial Tactics

The air combat in the Pacific during World War II was defined by exceptional aircraft designs and innovative aerial tactics. From the agile Japanese Zero to the resilient Allied fighters, each played a crucial role in shaping dogfights and strategic objectives.

Design Excellence: Zero and Its Predecessors

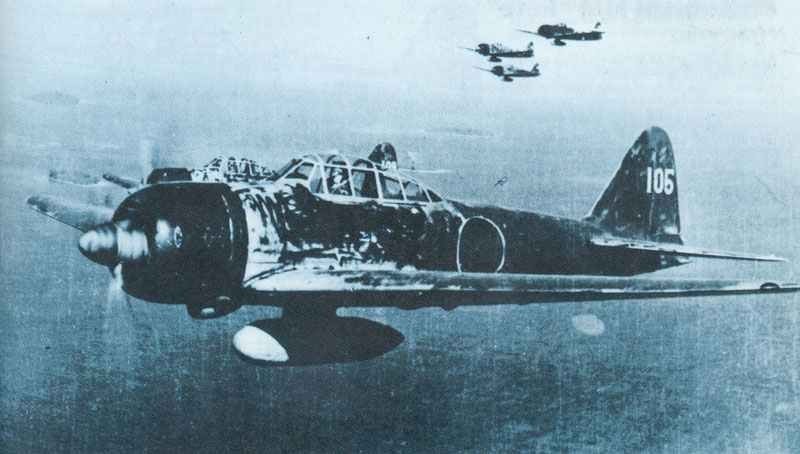

The Mitsubishi A6M Zero, often called simply the Zero, was a marvel of Japanese engineering. Known for its unmatched agility, lightweight design, and long operational range, it allowed Japanese pilots like Saburo Sakai to outmaneuver many Allied planes early in the war.

Equipped with a powerful engine and 20mm cannons, the Zero dominated the early months of the war. However, its lack of armor and self-sealing fuel tanks made it vulnerable to heavy return fire. While impressive in design, its drawbacks were exposed as more advanced Allied aircraft were introduced.

Dogfight Dynamics and Allied Aircraft

As the war progressed, Allied forces developed aircraft that could challenge the dominance of the Zero. The Grumman F4F Wildcat and F6F Hellcat were pivotal in turning the tide. The Wildcat, although slower, had better armor and firepower.

Later, the Hellcat emerged with improved speed and durability, helping secure air superiority. Meanwhile, the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk and Supermarine Spitfire contributed significantly, with the Spitfire’s agility and the Warhawk’s robust build aiding in various missions. The Douglas SBD-3 Dauntless, a dive bomber, supported naval engagements, delivering precise strikes on enemy targets.

Biography of Saburo Sakai

Saburo Sakai was a notable Japanese fighter ace and veteran of the Imperial Japanese Navy. He achieved many aerial victories and survived intense battles in World War II. His life was marked by his early struggles, his accomplishments as a pilot, and his experiences later in life.

Early Life and Entry into the Imperial Navy

Saburo Sakai was born on August 25, 1916, in Saga Prefecture, Japan. He grew up in a rural area and faced financial hardships early on. To improve his situation, he joined the Imperial Japanese Navy at the age of 16.

Sakai excelled in his military training and became part of the Tainan Air Group. This unit played a significant role in many early campaigns in the Pacific.

Over time, Sakai rose through the ranks, showing exceptional skill as a pilot. His early career set the foundation for his later achievements as a fighter ace.

Aerial Victories and Renown as a Fighter Ace

Saburo Sakai gained fame as a skilled pilot during World War II. He is officially credited with 28 aerial victories, which included shared wins. This rank earned him the title of lieutenant junior grade.

Sakai engaged in numerous dogfights, including those over Guadalcanal. Despite being severely wounded in an encounter on August 7, 1942, he managed to pilot his aircraft back to his base at Rabaul, covering 640 miles.

His ability to overcome injuries and continue fighting enhanced his reputation. Sakai remains one of Japan’s most recognized aces, known for his courage and tenacity in the air.

Kamikaze Mission and Later Years

Later in the war, Sakai was ordered to participate in a kamikaze mission. He and his squadron chose not to follow through with the mission, surviving the war.

Post-war, Sakai became a prominent figure, sharing his experiences and insights about air warfare through books and interviews. He co-authored “Samurai!” with Martin Caidin, a detailed account of his life.

Saburo Sakai passed away on September 22, 2000, leaving behind a legacy of bravery and resilience. His life story continues to be an inspiration to many, both in Japan and worldwide.

Factual report on the air war in the Pacific by Japanese Zero ace Saburo Sakai

Factual report on the air war in the Pacific by Japanese Zero ace Saburo Sakai. Operations over New Guinea in the summer of 1942.

From mid-April to mid-August 1942, the days seemed to merge seamlessly into one another. Life became an endless repetition of fighter missions, escort duties for our fighter planes over Moresby or alarm launches against enemy incursions. The Allies seemed to have an inexhaustible supply of aircraft. Not a week went by without the enemy suffering losses, and yet they kept coming back. In twos, threes or dozens.

In 1942, none of our fighter planes had any armour for the cockpit, nor did the Zeros have self-closing fuel tanks like the American planes had. And as the enemy very quickly discovered, a sheaf from their 0.50-in (12.7-mm) MGs was enough to set a Zero’s fuel tanks ablaze.

Despite this, not a single one of our pilots carried a parachute. This fact has led to the misconception in the West that our leadership valued our lives less, dismissed the pilots as expendable commodities and regarded them more as pawns than human beings. That is completely wrong. Every man was assigned his parachute. The decision to fly without it was solely our decision and not the result of any orders from above. In fact, although we were not ordered to wear the parachute, we were urged to wear it in combat. In some places, the commander insisted that parachutes were worn and the men had no choice but to put them in the aircraft. However, the harnesses were often not fastened and the parachute was simply used as a seat cushion.

We didn’t have much in mind with the parachute, because for us it was nothing more than a hindrance to our freedom of movement in the cabin during aerial combat. It was difficult to move our arms and legs when they were constricted by straps. But there was another equally compelling reason not to wear a parachute in combat. The majority of our battles with enemy fighters took place over their own terrain. To bail out over enemy territory, however, was completely unthinkable, for such an act would have been tantamount to a willingness to be taken prisoner, and nowhere in the Japanese military code or in the traditional ‘bushido’ (samurai code) can one find the abhorrent words ‘prisoner of war’. There were no prisoners. A man who did not return from battle was simply dead. No brave fighter pilot would allow himself to be taken prisoner by the enemy. That was absolutely unimaginable.

During the month of June, we encountered an ever-increasing number of enemy fighters and bombers. We were told that the enemy was in the process of reinforcing their air forces in this area and that we would have to step up our operations from now on. Everyone realised that we would now need every Zero we could get hold of. The enemy cleared more and more deployment sites in the jungle area around Port Moresby.

When a Japanese army division landed in Buna, 110 miles (180 km) south of Lae, on 21 July, a new phase of fighter operations began for us. The troops immediately began a forced march inland through the jungle towards Port Moresby. On the map, this operation looked easy enough, as Buna seemed to be just a stone’s throw from Moresby, across the Papuan peninsula.

But the maps of the jungle-covered islands are one thing, and the cruel reality there in the dense jungle is quite another. The Japanese high command made a terrible and fatal mistake when it threw its troops into the attack on Moresby. Even before the battle was over, Japan had suffered one of its heaviest blows in the war.

The land attack was an act of pure desperation. Originally, our high command had planned a massive landing operation against Moresby, but this plan was dropped on 7 and 8 May, during the naval battle in the Coral Sea, after two enemy aircraft carriers clashed with two Japanese in the first naval engagement in which neither surface craft fired a single shot against the other. Each unit used its aircraft to hammer the enemy. We may have won the battle, but the enemy had achieved its objective: the landing operation was called off.

After the landing at Buna, headquarters in Rabaul ordered us to call off our air attacks on Moresby and to provide constant air support for the bridgehead. The landing at Buna was only part of a larger operation that was doomed to failure even before it really began. It was not the jungle alone that proved to be a danger of immense proportions, but the complete lack of understanding of the problems of logistics on the part of the troop command that hampered our soldiers.

During the day, our base in Lae juggled with its 20 or 30 operational fighters to keep between six and nine Zeros in the air over Buna at all times, while maintaining sufficient reserves for the airfield defence. The air screen over Buna was smaller than it should have been, but our fighters managed to prevent major attacks to destroy the bridgehead.

Buna was a shock to me when I flew my first patrol. I had seen many landing operations from the air, but never before had I witnessed such a helpless attempt to supply a battle-hardened infantry division. Soldiers stomped across the beach and dragged supply crates into the jungle. A whole two small transport ships, with a submarine chaser as escort, lay off the beach unloading supplies.

War’s End and Legacy

The conclusion of World War II in the Pacific marked significant shifts in military and global dynamics. This period saw critical decisions by Emperor Hirohito leading to Japan’s surrender and changes in aviation, impacting pilots and aircraft carriers.

Emperor Hirohito and Japan’s Surrender

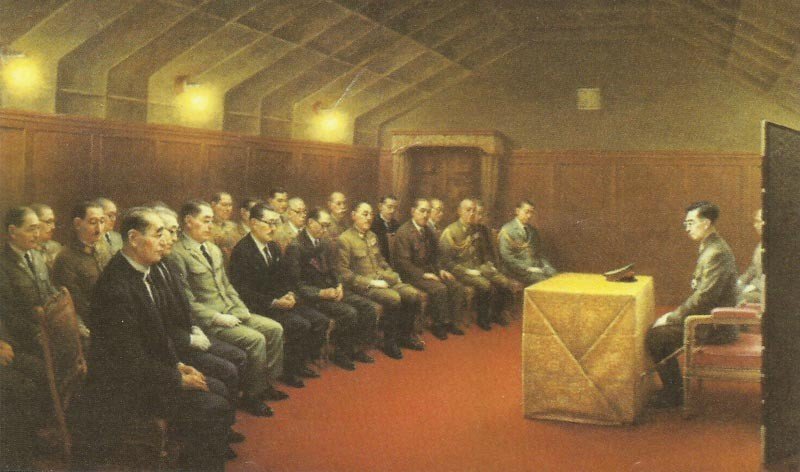

Emperor Hirohito played a pivotal role in Japan’s decision to surrender. After the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, he took steps to end the war to prevent further destruction.

His broadcast on August 15, 1945, marked the first time he addressed the Japanese public directly, explaining the decision to surrender. This announcement ushered in a new era for Japan, moving away from militarism and towards rebuilding the nation.

The surrender also ended Japan’s involvement in the Second Sino-Japanese War. The ceasefire paved the way for recovery and diplomatic relations with other nations. Hirohito’s influence was crucial in shaping Japan’s post-war identity.

Post-War Recognition and Aviation Influence

The war’s end did not slow the recognition of leading aces like Saburo Sakai. These pilots were celebrated for their skills and bravery in battle. Their stories inspired future generations of aviators in Japan and beyond.

The conflict spurred innovations in aircraft design, significantly influenced by Jiro Horikoshi’s work on planes like the Mitsubishi A6M Zero. These advancements laid groundwork for post-war aviation technologies.

American carrier pilots also gained fame, demonstrating the strategic importance of aircraft carriers in naval warfare. These changes highlighted how World War II shifted military tactics, emphasizing air superiority and technology’s role in modern combat.

Frequently Asked Questions

During the air war in the Pacific, pilots faced intense battles, challenging conditions, and evolving technology. Saburo Sakai stood out with his exceptional skills and flying tactics.

What were the major challenges faced by pilots in the Pacific air war during WWII?

Pilots dealt with long flights over open ocean, which was demanding due to limited navigational aids. They faced harsh weather conditions and the threat of enemy aircraft and anti-aircraft fire. The need for precise fuel management was critical during these missions.

What distinguished Saburo Sakai from other Japanese fighter pilots?

Saburo Sakai earned his reputation through his flying skills, courage, and successful missions. Known for his excellent marksmanship, he survived many dangerous encounters. Sakai’s ability to adapt to changing tactics and his devotion to duty set him apart from his peers.

What types of aircraft did Saburo Sakai fly, and how did they impact his success?

Sakai primarily flew the Mitsubishi A6M Zero, a highly maneuverable and lightweight fighter. The Zero’s agility and long-range capabilities provided Sakai with advantages in dogfights. This aircraft played a significant role in his aerial victories.

How did Saburo Sakai’s tactics contribute to his reputation as an ace pilot?

Sakai’s tactics included using surprise and speed to outmaneuver opponents. His careful attention to conserving ammunition and maintaining situational awareness was key. He often employed hit-and-run strategies to minimize exposure to enemy fire.

What were the implications of aerial combat in the Pacific on the overall outcome of WWII?

Aerial combat significantly affected naval battles and influenced strategies. Control of the air allowed for more effective naval blockades and amphibious landings. The air war in the Pacific contributed to the eventual victory of the Allied forces over Japan.

How did the experiences of Japanese flying aces like Saburo Sakai differ from their American counterparts?

Japanese aces like Sakai often flew without parachutes, accepting greater risk. They typically received extensive training, focusing on developing piloting skills from an early age. American pilots had more advanced technology at their disposal but faced different operational challenges, such as longer supply lines and varied geographic conditions.

References and literature

Flugzeuge des 2. Weltkrieges (Andrew Kershaw)

Samurai! (Saburo Sakai)