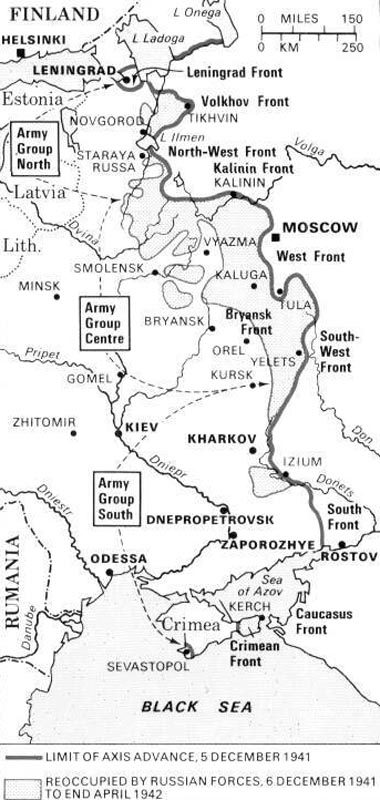

The Second and Third Soviet Counteroffensive in the Winter of 1941-42, and the Orders of Battle of the Wehrmacht of 22 April 1942.

The second Soviet counter-offensive

Table of Contents

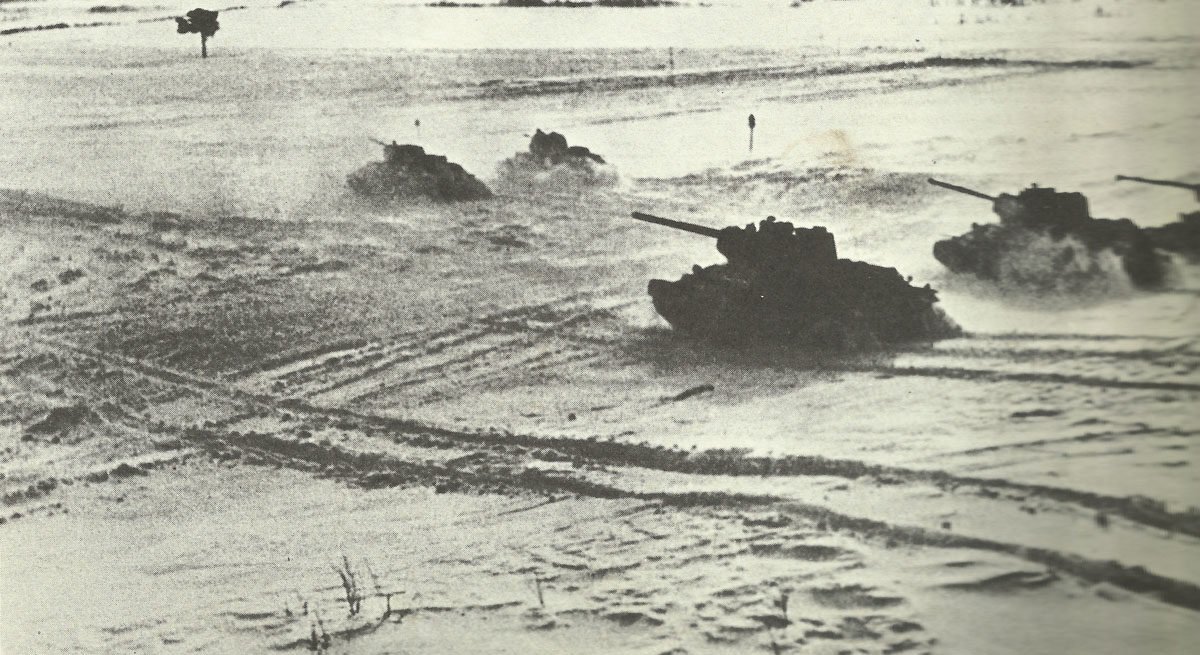

Against the contrary advice of several Red Army commanders, Stalin ordered an offensive series to begin along the entire Eastern Front in the first ten days of 1942.

In the north, an offensive by the 2nd Shock Army opened a narrow corridor through the German line in front of the siege ring outside Leningrad along the Volchov River. Cut off once, then reconnected with the Soviet front line, then cut off a second time, this army could not be effectively reinforced. Even the dispatch of one of Stalin’s most popular and capable commanders, General Andrei Vlasov, who had distinguished himself in the defence of Moscow, could not change the situation. Vlasov himself was taken prisoner in the summer, together with the survivors of his army and then tried in vain to raise an army from Soviet prisoners of war to fight alongside the Germans for an independent, non-Stalinist Russia.

Further south, the Red Army tore open the link between the German Army Groups North and Centre, penetrating deep into the rear of the latter and also isolating a small German force at Cholm and a larger one of nearly 100,000 troops at Demyansk.

The Germans, however, succeeded in holding both pockets in fierce fighting and with supplies from the Luftwaffe, until in the spring both garrisons could be disposed of by advances from the rest of the German front.

In the spring of 1942, the recapture of these areas seemed to confirm the tactics of the Winter Battle and leave a front line that offered at least some semblance of a chance to close the gap to Army Group Centre, which still stood around Rzhev.

Here, too, the Germans had succeeded in holding a key position and in clearing the threatened link to the south to Vyazma on the main railway and the road to Smolensk.

With his forces worn down by the efforts of the counter-offensive in December and deprived of needed reinforcements by the strategic advances in the north and south, Zhukov’s forces pushed the German troops back but could neither surround nor break through the front of Army Group Centre.

A massive breakthrough into the southern part of this front by forces led by General Belov and supported by several large airborne landings – the largest Soviet parachute operation of the war – still did not have the punch needed to cut off the German 9th and 4th Armies as planned. Soon Belov’s own forces and the partisans united with them were cut off behind the front itself and, like Vlasov’s 2nd Shock Army in the north, wiped out.

Further south, the Soviets were able to capture and hold the vital town of Kirov, cutting off the main north-south railway line from Vyazma to Bryansk. But apart from pushing the Germans back from the southern approaches to Moscow, they were unable to achieve the more spectacular objectives set for them by the Stavka.

An advance across the Donets at Izyum, aimed at cutting off the German positions at Kharkov in the north, destroying the German 6th Army and 1st Panzer Army in the south and at least reaching the Dnieper, was intercepted by the Germans and ended in a frontline bulge.

German troops pushed out of Rostov were able to hold a front along the Mius River. It took some hard fighting – and the replacement of the German Army Group Commander, soon followed by the death of his successor – but here both sides were equally exhausted.

On the Crimean Peninsula, German attempts to complete their conquest by capturing the major naval base of Sevastopol were frustrated by a Soviet amphibious operation across the Kerch Strait, which allowed them to retake the eastern part of Crimea. But here too, further Soviet landings and offensive operations were eventually brought to a halt by the Germans.

An uneven, jagged front marked the failure of German efforts to defeat the Soviet Union in a swift campaign in 1941, and likewise of Soviet hopes to crush the German invaders in a broad strategic offensive in the first weeks of 1942.

Just as Hitler had underestimated the Soviet Union’s resilience, Stalin made the same mistake with the Wehrmacht.

The Third Soviet Offensive

Stalin had underestimated the German forces and led the Red Army, which wanted to achieve far too much at once, to a great victory, but without destroying the German armies.

In their view, offensives could only be effectively launched in the autumn, provided that a new German summer offensive was repulsed.

Like his military leaders, Stalin believed that the German summer offensive of 1942 would take place on the central front against Moscow. This opinion was obviously fuelled by the obvious proximity of the German lines to the Soviet capital – some 75 miles (120 kilometres) – and the desperation with which the Germans had fought bitterly and successfully for the area around Rzhev – a place that could have no other purpose for them except to serve as a starting point for a new offensive against Moscow.

Moreover, the impression that the Wehrmacht were going to attack there was so effectively reinforced by a carefully crafted German deception operation that all indications of a very different plan of attack for 1942, supplied by both Soviet intelligence and the Western powers, were dismissed as feints.

Unlike his military leaders, however, Stalin did not think it wise to wait for the German blow. He therefore ordered a series of offensive operations in the spring, hoping thereby to upset German plans.

Of these Soviet offensives, however, only a small attack in the far north and a large one in the Kharkov area could be carried out before the German summer offensive began.

On the Litsa River front off Murmansk, a Soviet attack was broken off at the end of April 1942 after minimal gains and very heavy losses.

On the German side, the majority of those in charge still looked to the future with confidence. However, there were exceptions when the chief of construction and development of the Luftwaffe, the famous aviator Ernst Udet, committed suicide on 17 November 1941 out of despair at the situation. He became the model for Carl Zuckmeier’s ‘Des Teufels General‘ (‘The Devil’s General’).

In the same month, the Commander-in-Chief of the Reserve Army, General Fritz Fromm, and the Chief of the Armaments Office, Fritz Todt, pleaded with Hitler to make peace. On 20 March 1942, the Chief of Armed Forces Intelligence, Admiral Canaris, judged to Fromm that the war could no longer be won.

Adolf Hitler himself, however, was of a different opinion. He had also realized earlier than most that the campaign in the East would last into 1942.

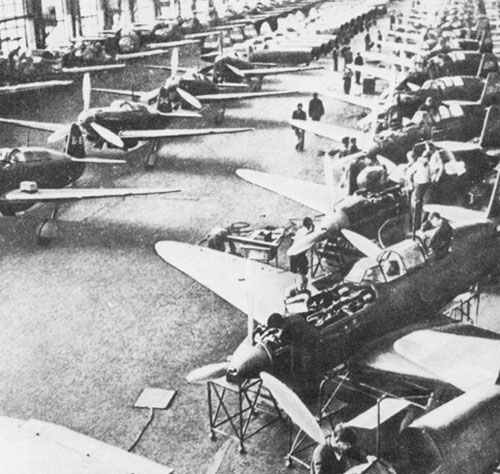

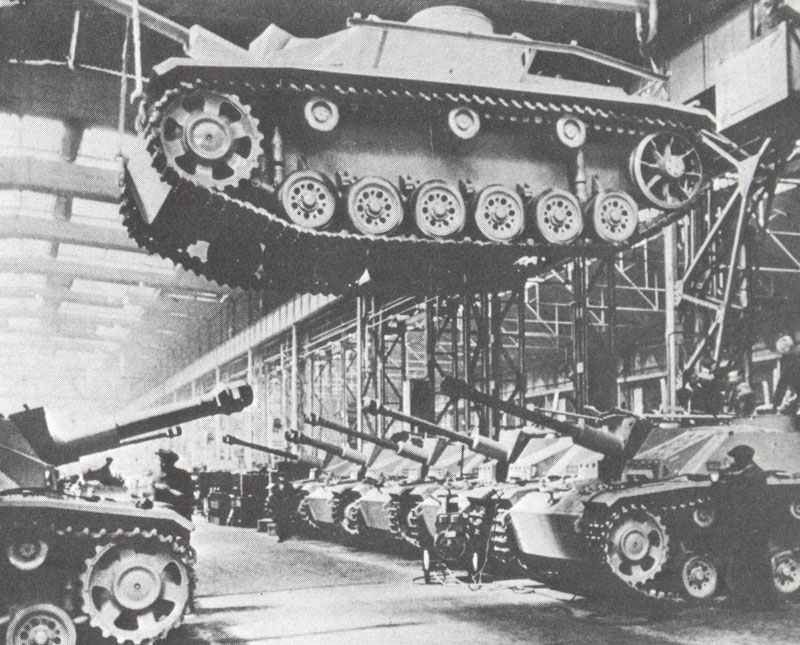

So great plans were set in motion to rebuild the German army, even though it could never again reach the strength of the summer of 1941. Hundreds of thousands of German workers were transferred from industry to the army. Instead of the expected reduction in the number of divisions – so that the air force and the navy could be upgraded for the fight against Britain and the United States – the number of divisions may have had to be increased.

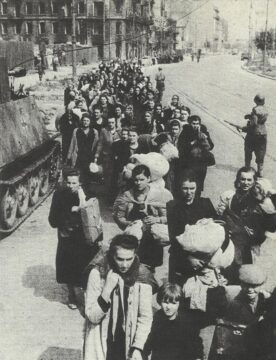

The workers detached from industry to the army were to be replaced by Russian prisoners of war, most of whom, however, had starved to death or otherwise perished in the meantime.

Since there were not enough voluntary workers from abroad, a huge forced labour programme was also set up with civilians from the occupied eastern territories.

Inevitably, the time of the cosy home front in Germany was over, and the armament industry had to be brought up to speed. The new guidelines on the armament programme of 10 January 1942 show quite clearly that the whole concept of ‘Blitzkrieg’ had failed.

No matter how much Hitler might push the mobilization of industry and manpower, and no matter how much he might rejoice at the prospect of an early spring on the Eastern Front, the army could not fight the battle alone.

The defeat of December 1941 and January 1942 only reinforced the Germans’ inclination to use the Luftwaffe primarily to support ground forces. Even more drastically than before, the Luftwaffe was kept out of any strategic role and tied solely to tactical support of the Army. But even the Luftwaffe would not be enough to enable the Army to launch another major offensive in the East.

The German allies would now have to help. The Romanians were asked to maintain and further develop the considerable forces they already had in the field, while Italy and Hungary were expected to bring their corps contingents up to army strength.

Mussolini, as usual, showed more enthusiasm than judgement in this project, and the Hungarians delayed it as best they could.

Crucially, however, at German insistence, numerically strong contingents of poorly equipped and trained, and often poorly led, troops were assembled and sent off to play a major role in German-planned operations that were unlikely to arouse the enthusiasm of individual soldiers among the allies.

For most, the exodus ended in death and disaster, with them subsequently having to provide the pretext for their own and also Germany’s defeat.

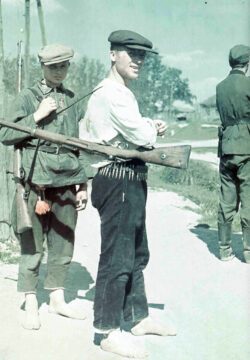

Although the German armies on the Eastern Front had by this time begun to recruit large numbers of captured Russian soldiers as auxiliary volunteers (‘Hilfwillige’, called ‘Hiwis’ for short), their attempts to organize armed units of volunteers recruited from Soviet citizens, whether or not they had previously been captured, were stopped by Hitler’s personal order.

The hope of gaining access to the oil deposits in the Caucasus, or at least keeping them from the Russians by cutting off the routes from there to the rest of the Soviet Union, had been dashed in 1941 by the Red Army’s successful resistance. This was now to be the top priority for 1942.

The conquest of the Donbass and the Caucasus would transfer the industrial and petroleum resources of these areas from Russian to German possession and open up the prospect of an advance across the Caucasus into the Middle East, where, perhaps aided by further German advances through Turkey and across North Africa, it was hoped to meet the Japanese advancing from the other side across the Indian Ocean.

The meeting of the Axis partners, the German and Japanese leaderships assured each other, would cut the Allied alliance and the lines of communication between their enemies.

These possibilities for the Germans and the Japanese were promising, just as they were dangerous for the Allies, and here especially for the Russians, but also for the British and Americans.

Only the Western powers recognized early on the immense danger they faced, while the Russians still expected a German attempt to take Moscow. But since the initiative now remained with Germany and Japan, it was their forces that would determine the sites for the decisive battles of 1942.

German Orders of Battle from April 22, 1942

Schematic layout of the German Wehrmacht from April 22, 1942:

Abbreviations:

Inf.Div. = infantry division

mot.Inf.Div. = motorized infantry division

Pz.Div. = Panzer (tank, armoured) Division

Sec.Div. = Security Division

Inf.Reg./Rgt. = Infantry Regiment

Brig. = Brigade

Btl. = Battalion

Cav. = Cavalry

Mt. = Mountain troops

Air = Airborne troops

Gr. = Group (battle group)

W.B. = Wehrmacht commander

Befh. r.H.G. = Commander Rear Army Area

Eastern Front

Army Group South

Army | Corps | Divisions |

|---|---|---|

Reserves | 20. Romanian Inf.Div. (at Odessa), 23. Pz.Div. |

|

Hungarian III. Corps | 6., 7., 9. Hungarian Light Div. (on transport to Orel, Tschernigov, Neshin) |

|

11. Army | Reserve | 72. Inf.Div., 22. Pz.Div., 2/3 from 10. Romanian Inf.Div., 2/3 from 19. Romanian Inf.Div. plus Romanian Army Command VII (Staff) |

LIV. | 22., 24. Inf.Div., 18. Romanian Inf.Div., 1/3 from 10. Romanian Inf.Div., 1. Romanian Mt.Div. |

|

Romanian Mt.Corps | Group Schröder (coatsal defence), 4. Romanian Mt.Div. |

|

XXX. | 50., 132. Inf.Div., elements 170. Inf.Div., 28. light Div., Romanian Cav.Rgt. 3 |

|

XXXXII. | 46. Inf.Div., bulk 170. Inf.Div., 1/3 from 73. Inf.Div., 1/3 from 19. Romanian Inf.Div., 8. Romanian Cav.Div. |

|

Commander of the isthmus | Romanian fast Rgt., Landsturm Btl. 286 |

|

Army Group v. Kleist | Reserves | 2/3 from 60. mot. Inf.Div. |

III. | 100. light Div., 14. Pz.Div., 1. Mt.Div., 1/3 from 60. mot.Inf.Div., elements 198. Inf.Div., Croat Inf.Rgt. 369, Wallonian Btl. 375 |

|

Corps Group Kortzfleisch (XI.); Reserves: 4. Romanian Inf.Div. | 2/3 of 2. Romanian Inf.Div., 298. Inf.Div., 2/3 from 68. Inf.Div. |

|

VI. Romanian (subordinatedt to Corps Group Kortzfleisch) | 1. Romanian Inf.Div., 113. Inf.Div., 1/3 from 2. Romanian Inf.Div. |

|

1. Panzer Army (subordinated to Army Group v. Kleist) | Reserves | 5. Romanian Cav.Div. (Group v. Förster), 6. Romanian Cav.Div (Romanian Cav.Corps) |

XIV. mot. | ||

XXXXIX. Mt. | 4. Mt.Div., 198. Inf.Div., Italian 3. Inf.Div. Celere, 1 Rgt. from 213. Security Div., Italian Bersaglierie-Rgt. 6 |

|

Italian Fast Corps | Italian 9. Pasubio, Italian. 52. Torino Div. |

|

17. Army (subordinated to Army Group v. Kleist) | LII. | 9., 111. Inf.Div. |

IV. | 76., 94., 295. Inf.Div., elements 16. Pz.Div. (Group von Witzleben) |

|

XXXXIV. | 97., 101. light Div., 257., 384. Inf.Div., 1/3 from 68. Inf.Div. |

|

2. Army | Reserves | elements of 454. Secruity Div., 102. Hungarian light Div. |

VIII. | 454. Security Div (Group Koch), 108. Hungarian light Div., Group Friedrich (Staff of 62. Inf.Div.) |

|

LI. | reinforced 44. Inf.Div., 297. Inf.Div. |

|

XVII. (Reserves: Slovak Artillery Rgt. 31) | 79., 294. Inf.Div. |

|

XXIX. | 57., 75. Inf.Div., Group Kraiß (168. Inf.,Div.) |

|

XXXXVIII. mot. | Group Gollwitzer (88. Inf.Div.,), 16. mot.Inf.Div., 9. Pz.Div. |

|

LV. | 45., 95. Inf.Div., Group Moser (299. Inf.Div.), SS-Brigade 1, 1/3 from 286. Security Div. |

|

Befh. r.H.G. Süd (South) | resp. elements of 213., 286., 444. Security Div. |

|

Hungarian occupation group | 105. Hungarian light Div. |

|

OKH Reserves at Army Group South | (all in transfer, except 3. Pz.Div.) | 383. Inf.Div. (to Rogatschev-Bobruisk), 387. Inf.Div. (to Kiev-Rovno), 71. Inf.Div. (to Charkov), 389. Inf.Div. (to Stalino), 3. Pz.Div. (at Charkov) |

Army Group Center

Army | Corps | Divisions |

|---|---|---|

Reserves | elements 6. and 7. Pz.Div. (in transfer to the West), 87. Inf.Div. |

|

2 Panzer Army | XXXV. | 262., 293. Inf.Div., 29. mot.Inf.Div. (bulk), 3. Pz.Div. (elements) |

LIII. | 112., 134., 296. Inf.Div., 25. mot.Inf.Div., 56. Inf.Div. (bulk), 10. mot.Inf.Div. (elements) |

|

XXXXVII. mot. | Group Eberbach (4. Pz.Div., elements 10. mot.Inf.Div.) |

|

each 2/3 from 211., 208. Inf.Div., 1/3 from 216. Inf.Div., 10., 29. mot.Inf.Div. (elements each), 17., 18. Pz.Div., 339. Inf.Div. |

||

4 Army | Reserves | Group Fehn (from staff and elements from 5. Pz.Div. and 15. Inf.Div.), Group AK 302 (Corps staff) with 1/3 from 31. Inf.Div. |

XXXX. mot. (Reserves: Luftwaffen ground combat group, Group Ramm and Reichelt) | 331. Inf.Div., 131., 211., 216. Inf.Div. (elements each), 19. Pz.Div., 10. mot.Inf.Div. (bulk), 403. Security Div. (elements), Group Schlemm (Luftwaffen ground unit) |

|

XXXXIII. (Arko 133) | 31. Inf.Div. (bulk), 10. mot.Inf.Div. (elements), 211. Inf.Div. (elements), 2/3 from 34. Inf.Div., 2/3 from 131. Inf.Div., 266. Security Div. (elements) |

|

XIII. | 52., 137., 263. Inf.Div., 260. Inf.Div. (bulk) |

|

XII. (including Group Werner and Group Haehnle) | 98., 268. Inf.Div., 17., 23., 216., 260. Inf.Div. (elements each), each 1/3 from 34., 131. Inf.Div., 5. Pz.Div. (elements), 10. mot.Inf.Div. (elements), Luftwaffen ground unit |

|

4 Panzer Army | Reserves | 267. Inf.Div., 213. Security Div. (elements) |

XX. (including Group Thoma) | 183., 258., 292. Inf.Div., 17., 20. Pz.Div. (bulk each), 2/3 from 255. Inf.Div. |

|

IX. | 35., 78., 197., 252. Inf.Div., 20. Pz.Div., 7. Inf.Div. (bulk), 7., 23., 78. Inf.Div. (elements each), 1/3 from 255. Inf.Div., 11. Pz.Div. (elements) |

|

V. | 5., 15. Pz.Div (bulk each), 3. mot.Inf.Div., 23. Inf.Div. (bulk) |

|

9 Army | Reserves | 246. Inf.Div., 7. Pz.Div. (bulk), 2., 5. Pz.Div. (elements each) |

XXXXI. mot. | 342. Inf.Div., 36. mot.Inf.Div., 2., 6. Pz.Div. (elements each), Brigade 900 (elements) |

|

Group Recke | 161., 162. Inf.Div., 129. Inf.Div. (bulk) |

|

VI. | 6., 26. Inf.Div., 256. Inf.Div. (bulk), 102., 339. Inf.Div. (elements each) |

|

XXXXVI. mot. | SS-Reich, 14. mot.Inf.Div., 206., 251. Inf.Div., 1/3 from 216. Inf.Div., 129., 328. Inf.Div. (elements each) |

|

XXIII. | 253. Inf.Div., 102. Inf.Div. (bulk), 1/3 from 110. Inf.Div., SS Cav.Brigade, 208., 256. Inf.Div. (elements each), 1. Pz.Div. (bulk), 2., 5. Pz.Div. (elements each) |

|

XXVII. | 110. Inf.Div. (bulk), 1/3 from 328. Inf.Div., 2/3 from 86. Inf.Div., 1., 5., 7. Pz.Div. (elements each) |

|

LVI.mot. (Group Decker) | each 1/3 from 86., 328. Inf.Div., 6. Pz.Div. (bulk), 2. Pz.Div. (elements, incl Group Decker) |

|

3 Panzer Army | LIX. (incl Group Schröder) | 205., 330. Inf.Div., each 1/3 from 218., 328. Inf.Div., 2/3 from 83. Inf.Div. |

1/3 from 83. Inf.Div. (incl staff), 81., 218. Inf.Div. (elements each) |

||

Befh. r.H.G. Center (Group von Schenckendorff) | 707. Inf.Div., 211. Security Div., 285. Security Div. (bulk), 403. Security Div. (elements), 11. Pz.Div. (elements and staff), 201., 203. Security Brigade |

|

OKH Reserves at Amy Group Center | 2/3 from 385. Inf.Div. (at Roslav), Inf.Rgt. GD (Gomel, refreshment), Corps staffs LVII. mot. (Mogilev), XXIV. mot., VII. (both approaching) |

Army Group North

Army | Corps | Divisions |

|---|---|---|

Reserves | 8., 12. Pz.Div. (elements each,under refreshments), 1/2 from 5. Mt.Div. (approaching) |

|

16 Army | Reserves | 123. Inf.Div. (elements), 281. Security Div. (elements) |

XXXIX. mot. (Reserves: 1/2 from Paratrooper Rgt. 2 approaching, 1/3 from 121. Inf.Div. approaching) | 1/3 each from 121., 122., 123., 329. Inf.Div. 8. Pz.Div. (bulk), Group Lang (elements 218. Inf.Div.), Group Scherer (staff of 281. Security Div.) |

|

II. (Reserves: Group Zorn with elements of SS-Totenkopf, staff 105. Corps, Group Eicke-Stb.) | 12., 30., 32., 290. Inf.Div., 123. Inf.Div. (bulk), each 1/3 from 218., 225. Inf.Div., SS-Totenkopf (bulk), 281. Sicherungs-Div. (elements) |

|

X. (incl Corps Group v.Seydlitz) | 18. mot.Inf.Div., 5., 8. light Div., 2/3 from 329. Inf.Div., 1/2 from 7. Mt.Div., each 1/3 from 81., 122. Inf.Div., 1 Btl. from Pz.Rgt.203, Police Rgt. North, 281. Security Div. (elements), Group Meindl (Luftwaffen field regiments) |

|

18 Army | Reserves | 12. Pz.Div., staff 5. Mt.Div. |

XXXVIII. | 250. Spanish Inf.Div., 58., 126. Inf.Div., SS-Brigade 2, 20. mot.Inf.Div. (elements), 285. Ssecurity Div. (staff and elements) |

|

I. | 11., 21., 61., 215., 254., 291. Inf.Div., each 1/3 from 93., 96., 121., 122., 212., 217. Inf.Div., each elements from 1., 81., 223. Inf.Div., 20. mot.Inf.Div. (bulk with staff), SS-Rgt. 9, 12. Pz.Div. (elements), Group Wünnenberg (bulk SS-Police-Div.), 207. Security Div. (elements), 1/2 from Paratroopers Rgt. 2, Brigade Risse, 1 detachment from Pz.Rgt. 203, Group von Basse (staff from 225. Inf.Div.) |

|

XXVIII. | 227., 269. Inf.Div., 1., 223. Inf.Div. (bulk each), 2/3 from 96. Inf.Div., 1/3 from 225. Inf.Div., 212. Inf.Div. (elements), 207. Security Div. (elements), LSAAH (elements), 1/2 from 5. Mt.Div., Police battalions |

|

L. (incl Group Jeckeln and sub-group Neidholdt) | SS-Norway, each 1/3 from 121., 385. Inf.Div., 285. Security Div. (elements), Police battalions |

|

XXVI. | each elements with staff from 93., 217. Inf.Div. |

|

Befh. r.H.G. North | each elements from 207., 281. Security Div. |

OKW Theaters of War

North

Army | Corps | Divisions |

|---|---|---|

Finish group Aunus | Connection staff North | 2/3 from 163. Inf.Div. |

Army commando Lapland | Reserves | 7. Mt.Div. (elements) |

III. Finish | 3. Finish. Inf.Div., SS-Nord, Finnish Jaeger Div. |

|

XXXVI. Mt. | 169. Inf.Div., 1/3 from 163. Inf.Div., reinforced Mt.Rgt. 139 |

|

Mt. Corps Norway | 2., 6. Mt.Div., 1/3 from 214. Inf.Div., 702. Inf.Div. (elements) |

|

Army commando Norway | Reserves | 3. Mt.Div. (1/3 still in transfer), 25. Pz.Div. (Oslo) |

LXXI. | 199., 230., 270. Inf.Div., 702. Inf.Div. (bulk) |

|

XXXIII. | 181., 196. Inf.Div. |

|

LXX. | 69., 280., 710. Inf.Div., 2/3 from 214. Inf.Div. |

Army Group D (Commander West)

Army | Corps | Divisions |

|---|---|---|

Reserves | 106., 167. Inf.Div., 10. Pz.Div. (all in delivery), 370., 371., 376., 377. Inf.Div. (in creation from 19th wave) |

|

Commander of the German troops in the Netherlands | 82., 719. Inf.Div. |

|

15 Army | XXXVII. | 304., 306., 321,, 323., 340. Inf.Div. |

XXXII. | 302., 332., 711. Inf.Div. |

|

LX. | 319., 320., 716. Inf.Div. |

|

1 Army | Reserves | Pz.Brigade 100 (without 1. detachment) |

XXXXV. | 357., 712. Inf.Div. |

|

7 Army | Reserves | 24. Pz.Div. |

XXV. | 305., 333., 335., 336., 709. Inf.Div. |

|

XXXI. | 327., 708., 715. Inf.Div. |

Southeast

Army | Corps | Divisions |

|---|---|---|

12. Army | Reserves | Inf.Rgt. 440 |

Fortress Div. Crete (from 713. Inf.Div., 160. Inf.Div. without Inf.Rgt. 440, instead Inf.Rgt. 125) |

||

The commanding general and commander in Serbia | 704., 714., 717., 718. Inf.Div. |

Africa

Army | Corps | Divisions |

|---|---|---|

Panzer Army Africa | Reserves | 90. light Div., Italian 25. Bologna, Italian 60 Sabrata (all Italian units in Cyrenaica) |

DAK | 15., 21. Pz.,Div. |

|

Italian XX. (mot.) | Italian 101. (mot.) Trieste, Italian 132. armoured div. Ariete |

|

Italian XXI. | Italian 102. Trento |

|

Italian X. | Italian 17. Pavia, Italian 27. Brescia |

Chief of Army Armament and Commander Replacement Army

in Germany: 7. Mt.Div. (only elements; in WK XIII), XXIII. Mt.Corps (staff, in WK XVIII)

Denmark: 416. Inf.Div.

References and literature

Krieg der Panzer (Piekalkiewicz)

World War II – A Statistical Survey (John Ellis)

Der 2. Weltkrieg (C. Bertelsmann Verlag)

Zweiter Weltkrieg in Bildern (Mathias Färber)

A World at Arms – A Global History of World War II (Gerhard L. Weinberg)

Der Grosse Atlas zum II. Weltkrieg (Peter Young)

Kriegstagebuch des Oberkommandos der Wehrmacht, Band 1-8 (Percy E. Schramm)