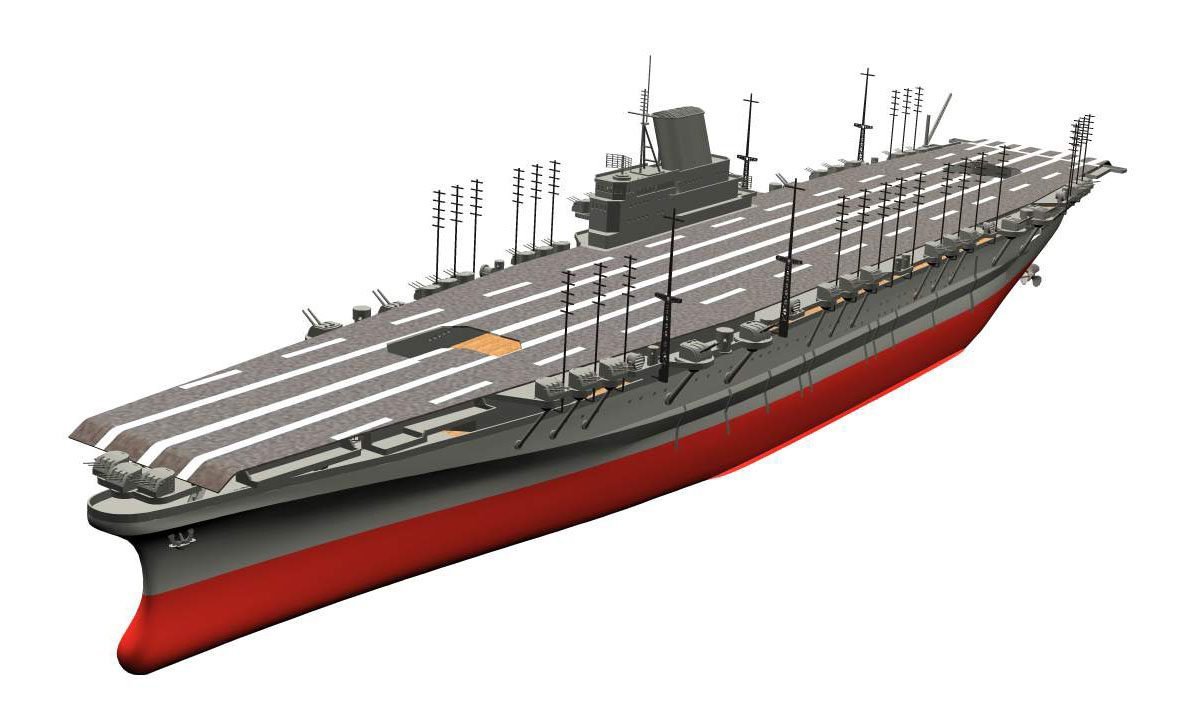

German Orders of Battle from 3 September 1941 and the Eastern Front after the successful start of Operation Barbarossa from the end of August 1941 until the failure of the German offensive in front of Moscow in December 1941.

The Eastern Front from September to December 1941

Table of Contents

About a month after the start of Operation Barbarossa, Hitler and many German officials still believed in July 1941 that their gamble had paid off.

For a short time it looked as if the war in the East had been won and the Germans could do as they pleased, both in the occupied Soviet Union and in the rest of Europe, while they were able to implement the preliminary planning for the next steps in the war against England. Hitler told his staff that Germany’s new frontier would be at the Urals, and whenever a new danger seemed to emerge beyond that line, German troops would push further east.

In those days of July 1941, when victory seemed inevitable, Hitler gave orders to starve out the Slav population in the East and the Russian prisoners of war and to have them reduced by forced labor and to prepare the Final Solution of the Jewish Question.

The euphoria of July also brought new decisions for the war in the West. On 14 July, Hitler ordered the reorientation of the armament program towards the Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine at the expense of the army, whose planned deployment was to include direct attacks on England and its shipping in the Atlantic as well as the British position in the Middle East.

As these new projects began to be undertaken, or at least considered, in late July, however, some in the German hierarchy began to grasp the realities of the situation at the front. Despite the enormous losses in men and matériel that the Russians had suffered, there was obviously both a continuing front and a steady, if not yet massive, flow of new formations and replacements.

Moreover, the Red Army men were fighting hard, there were local counterattacks, and there were signs of a revival of the Red Air Force, which the Germans had misjudged both in terms of its front-line strength and its replacement capabilities. The Soviet system was clearly holding together, and as news spread of the murder of all captured Red Army political officers, of the slaughter of scores of other prisoners of war and the appalling mistreatment of the rest, of the murder of tens of thousands of civilians – Jews, party officials, people in mental institutions, and anyone who looked unpleasant – it became increasingly clear to Soviet citizens on both sides of the front what fate awaited those who fell under German control.

From the days of World War I, the Russian population had retained the memory that the Germans fought hard and decisively, but generally treated prisoners and civilians decently. Now, however, it was obvious that there must have been a dramatic change.

The first signs of the unpleasant awakening at the Führer’s headquarters can be seen in the second half of July. In the first week of August, it began to be realized that the Caucasus and Murmansk would probably not be reached in 1941 and that the campaign could be expected to drag on into the next year.

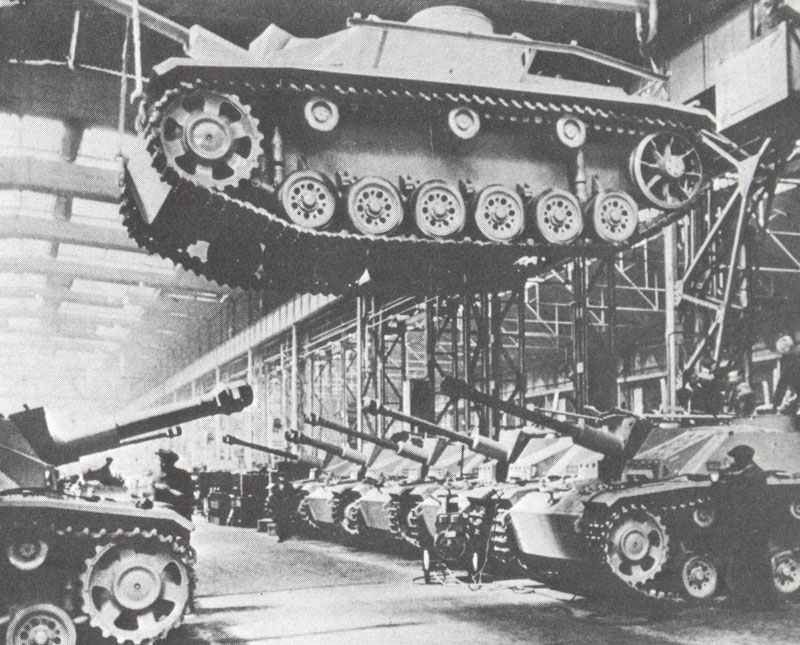

German units had to be refreshed and re-equipped, and in the ensuing lull of late July and August, decisions had to be made about the direction of the next offensives in the east. The very fact that such decisions about priorities for further major offensives were necessarily showed that the original German plan to bring about the collapse of the Soviet Union by massive hammer blows right at the beginning had failed.

Anyone who still had doubts about this was convinced by the heavy Soviet counterattacks on the central front. On July 20, 1941, the Germans had captured the town of Yelnya, 25 miles (40 kilometers) southeast of Smolensk, and on September 5 the Red Army drove them out again in one of the first local Soviet victories of the war.

The Germans now had to decide whether to resume the offensive on the central front or in the south and north. The very fact that they could not repeat the earlier simultaneous offensives on all three sections of the front shows the weakening of the German offensive strength while lengthening the front the farther east one goes, while Soviet resistance continued.

The relatively more successful defense of the Red Army or the less spectacular offensive successes of the Germans on the southern part of the front gave a peculiar twist to the German plans about the further course of action.

If the German troops advanced toward Moscow in the center, they risked a dangerously open flank at the southern end of such an advance, for which they lacked the reserves to cover. If they exploited the further advance in the center to get behind the Soviet forces still in the south in order to encircle them, however, they would lose time for the advance on Moscow.

The arguments were as vehemently debated then as they have been among experts since. A careful analysis of the Wehrmacht’s transportation and supply problems on the Eastern Front clearly shows that the Germans were simply unable to resume the offensive in the central part of the front immediately after they had reached the geographical limits of the supply system by truck on which the initial advance depended. Whatever was to be done next, first the rail links had to be restored so that they could bear the brunt of logistical support for operations farther east.

After some hesitation, Hitler decided to move some of the forces of Army Group Center to support the assaults on Leningrad in the north, while others were detached for an attack in the rear of the Soviet forces defending Kiev in the south.

Shortly thereafter, on September 11, Hitler was forced to change war production priorities again: The Army and antiaircraft defenses had to be given priority again so that the German Army could continue to fight in the East and the home front could be defended against British air attacks. The Navy and Air Force, the main means for the offensive against Britain and expected war against the U.S., would have to wait.

The renewed northern advance on Leningrad achieved considerable terrain gains, including a narrow advance on Lake Ladoga from the south, cutting off land links to the city and initiating a long and bitter siege.

Hitler had ordered that Leningrad not be invaded because at this point, unlike Stalingrad a year later, he did not want German troops in large cities to be involved in large-scale house-to-house fighting.

The major German operation on the southern part of the main front in the east involved the deployment of armored groups, one of which, previously deployed with Army Group Center, drove south to meet the other pincer of the armored attack north across the Dnieper River at Kremenchuk.

These operations, which converged about 150 miles (240 kilometers) east of Kiev, resulted in the destruction of strong Soviet forces in September 1941. The Germans took alone over 600,000 prisoners and captured thousands of guns. Nevertheless, the Soviet leadership was again able to build a new front.

Like Army Group North, Army Group South scored more local victories, occupying most of Crimea and much of central and eastern Ukraine, including the large city of Kharkov, and also advancing along the northern shore of the Sea of Azov. This advance culminated in the capture of Rostov at the mouth of the Don River on November 21, but here, as elsewhere, German offensive power was then at an end.

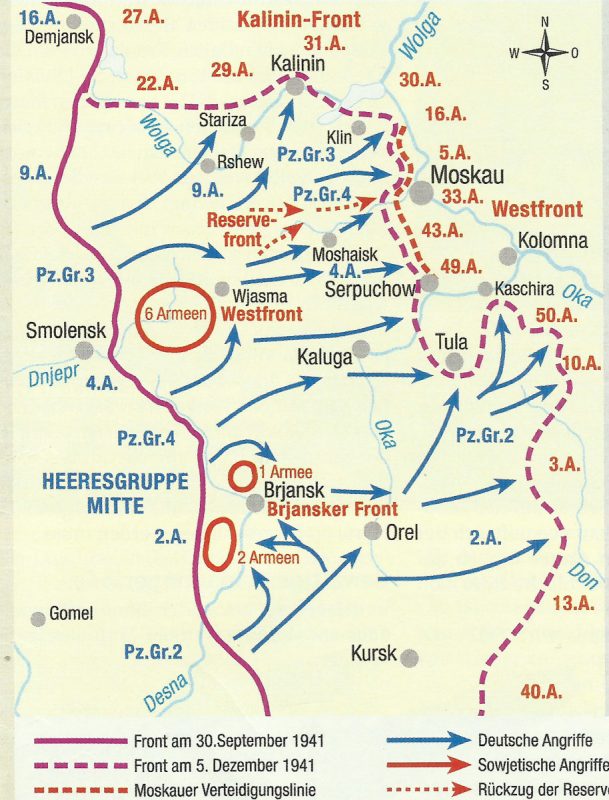

Assault on Moscow

In two major armored breakthrough and encirclement operations, the Germans tore through the main Soviet forces on this front, taking another 600,000 prisoners and advancing to within 50 miles (80 kilometers) of Moscow.

As German propaganda proclaimed final victory, the Soviet government evacuated most of the authorities from the capital to Kuibyshev, and a temporary panic ensued in Moscow.

But once again, Red Army reserves, newly formed units, and scraped-together formations and equipment held a new front with ferocious determination, while German offensive power waned because of lost or worn equipment, heavy casualties, and some degree of troop exhaustion. This, however, was not recognized by many in authority in the higher German command posts.

At the same time, the autumn rains that began in mid-October softened all roads into deep fields of mud and mire, making all movement nearly impossible and forcing a pause no later than October 26.

The leaders now had to decide whether to make another attempt to conquer Moscow, or to postpone it until next year. These considerations now clearly indicated that the original plan to crush the Soviet Union in a massive, rapid campaign had finally failed.

By the last months of 1941, it was already clear to every German commander that there would be another year of war in the East. Now the question was really only in which positions the German troops should stand during the winter in order to continue the campaign in 1942.

The prevailing opinion among the German military leadership was that it would be best to hold the positions reached in late October and early November, straighten the lines somewhat, and try to adopt a defensive posture in order to improve the very tight supply situation and give the exhausted troops some rest.

Others, including Hitler himself as well as the army’s commander-in-chief, Field Marshal von Brauchitsch and Chief of Staff General Halder, thought that a final push might bring them to Moscow and thus better winter quarters for the German troops. Such a local victory would also shatter the Soviet railroad and command system and would mean that the Russians would lose Moscow’s industrial facilities, as well as dealing them a major psychological blow.

A number of other factors contributed to this decision. The existing front line was not advantageous for defense, but by many at the top of the command structure, the actual deficient condition of the German fighting units was not recognized.

Perhaps most important, not only was the continuing fighting strength of the Red Army and the slowly reviving Red Air Force grossly underestimated, but German intelligence, as it had been before and for the rest of the war, was very wrong in its general assessment of Soviet strength.

The Germans had no real idea of the speed with which the Soviet Union was mobilizing new forces to throw into battle, and they were so far off in their estimate of Soviet strength that they claimed in early December that the Red Army had neither the ability nor the intention to launch a significant counteroffensive of its own.

After the onset of frost, which made the sodden ground passable again, the final assault on Moscow began on November 15, 1941, despite inadequate refreshment of the German units.

The Soviet Western Front held off the Germans in fierce fighting north, west, and south of Moscow in the mud and then in the freezing cold. Units of Panzer Group 4 under Hoepner reached the Volga Canal 18 miles (30 kilometers) from Moscow’s city center, but then remained stranded.

The assault unit of the Army Pioneer Battalion 62 even reached the suburb of Khimki, less than 5 miles (eight kilometers) from the city limits, and in the scissors telescopes could already see the Kremlin, (10 miles) 16 kilometers away.

But on December 5, 1941, the German troops, inadequately equipped for winter warfare, were forced to withdraw after numerous sorties. Since the second half of November, German losses due to frostbite exceeded the number of casualties in combat, and in the subzero temperatures of 30 to 40 degrees Celsius that now set in, German engines and machine guns failed.

Thus, Operation Barbarossa had finally failed.

German Orders of Battle from September 3, 1941

Schematic layout of the German Wehrmacht from September 3, 1941:

Eastern Front

Army Group South

Army | Corps | Divisions |

|---|---|---|

OKH-Reserves (for full Eastern Front in Germany) | 5. Pz.Div. (Wehrkreis III) |

|

Reserves | Slovak Fast Division |

|

Romanian 4. Army | Romanian XI. | 8., 14. Romanian Inf.Div., Romanian Guard Div. |

Romanian I. | 21. Romanian Inf.Div., Romanian Border troops Div |

|

Romanian IV. | 3., 5., 6., 7., 11. Romanian Inf.Div., 9. Romanian Cav.Brig. |

|

Romanian V. | 13., 15. Romanian Inf.Div.,, 1. Romanian Cav.Brig. |

|

11. Army | Reserves | 50., 170. Inf.Div., LSSAH |

LIV. | 72., 73. Inf.Div. |

|

XXX. | 22., 46. Inf.Div. |

|

XXXXIX. Mountain | 1., 4. Mt.Div. |

|

Romanian 3. Army (subordinated to German 11. Army) | Romanian Mountain Corps | 1., 2., 4. Romanian Mt.Brig. |

Romanian Cav.Corps | 5., 6., 8. Romanian Cav.Brig. |

|

Panzer Group 1 | XIV. mot. | 16., 25. mot.Inf.Div., 9. Pz.Div. |

III. mot. | 13., 14. Pz.Div., 60. mot.Inf.Div., 198. Inf.Div., SS-Wiking |

|

XXXXVIII. mot. | 16. Pz.Div. |

|

Hungarian Fast Corps | 1., 2. Hungarian mot.Brig., 1. Hungarian Cav.Brig. |

|

Italian Fast Corps | Italian 3. fast Div., Italian 52. Div. Torino, Italian Pasubio-Div. |

|

17. Army | Reserves: LV. Korps | 9., 57., 295. Inf.Div. |

LII. | 97., 100. light Div., 76. Inf.Div. |

|

XI. | 125., 239., 257. Inf.Div., 101. light Div. |

|

XXXXIV. (Group v.Schwedler) | 68., 297. Inf.Div. |

|

IV. (Group v.Schwedler) | 24., 94. Inf.Div. |

|

6. Army | Reserves | 11. Pz.Div., 56., 62., 168. Inf.Div. |

XXXIV. | 132., 294. Inf.Div. |

|

XXIX. | 71., 75., 95., 299. Inf.Div., 99. light Div. |

|

XVII. | 44., 296., 298. Inf.Div. |

|

LI. | 79., 98., 111., 113., 262. Inf.Div. |

|

Commander Rear Army Territory | 213., 444., 454. Security Div., Slovak Security Div., SS-Brigade 1 |

Army Group Center

Army | Corps | Divisions |

|---|---|---|

Reserves | Staff LIII. Corps | 52., 162. 252. Inf.Div. |

2. Army | XXXV. | 45., 112. Inf.Div. |

XIII. | 17., 134., 260. Inf.Div. |

|

XXXXIII. | 131., 293. Inf.Div. |

|

Panzer Group 2 | Reserves: Staff XXXXVI. Corps | 1. Cavalry Div., SS-Div. Das Reich |

XXIV. mot. | 3., 4. Pz.Div., 10. mot.Inf.Div., Inf.Reg. Grossdeutschland |

|

XXXXVII. mot. | 17., 18. Pz.Div., 29. mot.Inf.Div. |

|

4. Army | Reserves | 10. Pz.Div., 2/3 each of 167. and 263. Inf.Div. |

XII. | 31., 34., 258. Inf.Div., 1/3 of 167. Inf.Div. |

|

VII. | 23., 197., 267. Inf.Div. |

|

XX. | 7., 78., 268., 292. Inf.Div. |

|

IX. | 15., 137. Inf.Div., 1/3 of 263. Inf.Div. |

|

9. Army | Reserves | Spanish 250. Inf.Div., |

VIII. | 7. Pz.Div., 14. mot.Inf.Div., 8., 28., 87., 161., 255. Inf.Div. |

|

V. | 5., 35., 106., 129. Inf.Div. |

|

VI. | 6., 26., 110., 206. Inf.Div. |

|

Panzer Group 3 | Reserves | 900. mot.Brig. |

LVII. mot. | 19., 20. Pz.Div. |

|

XXXX. mot. | 256., 102. Inf.Div. |

|

XXIII. | 86., 251., 253. Inf.Div. |

|

Commander Rear Army Territory | 221., 296., 403. Security Div., 339., 707. Inf.Div., SS-Horsemen-Brigade |

Army Group North

Army | Corps | Divisions |

|---|---|---|

OKH-Reserves | 183. Inf.Div. |

|

16. Army | II. | 12., 32., 123. Inf.Div. |

LVI. mot. | 3. mot.Inf.Div., SS-Totenkopf-Div. |

|

X. | 30., 290. Inf.Div. |

|

I. | 11., 21., 126. Inf.Div., 18. mot.Inf.Div. |

|

XXVIII. (Group Schmidt) | 96., 121. Inf.Div. |

|

XXXIX. mot. (Group Schmidt) | 12. Pz.Div., 20. mot.Inf.Div., 122. Inf.Div. |

|

Panzer Group 4 | L. | Police-Div., 269. Inf.Div. |

XXXXI. mot. | 1., 6., 8. Pz.Div., 36. mot.Inf.Div. |

|

18. Army | Reserves | 254. Inf.Div. |

XXXVIII. | 1., 58. Inf.Div. |

|

XXVI. | 93., 291. Inf.Div. |

|

XXXXII. | 61., 217. Inf.Div., Group Friedrich |

|

Commander Rear Army Territory | 207., 281., 285. Security Div. |

AOK Norway

Army | Corps | Divisions |

|---|---|---|

OKH-Reserves | Connection staff Nord | 163. Inf.Div. (with Finnish Army) |

Reserves | 6. Mt.Div. (transfer) |

|

Finnish III. | Finnish 3. Inf.Div., SS-Div. Nord (elements) |

|

XXXVI. (Staff SS-Nord) | Finnish 6. Inf.Div., 169. Inf.Div., SS-Div. Nord (eleménts) |

|

Mountain Corps Norway | 2., 3. Mt.Div. |

|

Section Staff North Norway | 199., 702. Inf.Div. |

|

XXXIII. | 181., 196. Inf.Div. |

|

LXX. | 69., 214., 710. Inf.Div. |

OKW Theaters

Army Group D (Commander West)

Army | Corps | Divisions |

|---|---|---|

Commander of the units in the Netherlands | 82., 719. Inf.Div. |

|

15. Army | XXXXVII. | 208., 227., 304., 306., 320., 321., 340. Inf.Div. |

XXXII. | 225., 302., 332., 336., 711. Inf.Div. |

|

LX. | 83., 216., 319., 323., 716. Inf.Div. |

|

1. Army | Reserves | Pz.Brig. 100, Pz.Brig. 101 |

XXVII. | 327., 335., 337. Inf.Div. |

|

XXXXV. | 215., 342. Inf.Div. |

|

7. Army | Reserves | 2. Pz.Div. |

XXV. | 205., 211., 709., 712. Inf.Div. |

|

LIX. | 81., 246., 305., 715. Inf.Div. |

|

XXXI. | 88., 212., 223., 333., 708. Inf.Div. |

Southeast

Army | Corps | Divisions |

|---|---|---|

12. Army (Wehrmachts Commander for Southeast) | XVIII. Mountain | 5. Mt.Div., 164., 713., Inf.Div., Inf.Reg. 125 |

LXV. | 704., 714., 717., 718. Inf.Div. |

Africa

Army | Corps | Divisions |

|---|---|---|

Panzer Group Africa | Reserves | 15. Pz.Div. |

DAK | 21. Pz.Div., Italian Div. Savona, Fortress troops Bardia |

|

Italian XXI. | Italian. Div. Brescia, Pavia, Bologna, German reinforced Rifle Reg. 115 |

Chief of Army Armament and Commander Replacement Army

Commander of German troops in Denmark (218th Inf.Div.)

References and literature

Der 2. Weltkrieg (C. Bertelsmann Verlag)

Zweiter Weltkrieg in Bildern (Mathias Färber)

A World at Arms – A Global History of World War II (Gerhard L. Weinberg)

Der Grosse Atlas zum II. Weltkrieg (Peter Young)

Kriegstagebuch des Oberkommandos der Wehrmacht, Band 1-8 (Percy E. Schramm)