Operation Torch, the Allied landings in North Africa.

On November 8, 1942, a force of over 70,000 Allied troops invaded Vichy-French North-West Africa.

Allied landings in North Africa 1942

Table of Contents

On the morning of November 8, 1942, a force of over 70,000 American and British soldiers went ashore on the coast of Vichy-French North-West Africa during Operation Torch, and a period of close Anglo-American co-operation began. Altogether over 500 ships had carried and guarded the assault force: 102 of them crossing the Atlantic from America; the remainder sailing in two convoys – one fast and one slow – from Britain.

They all arrived at their destinations within a few hours of each other and a pattern of smooth timing and organization had been set.

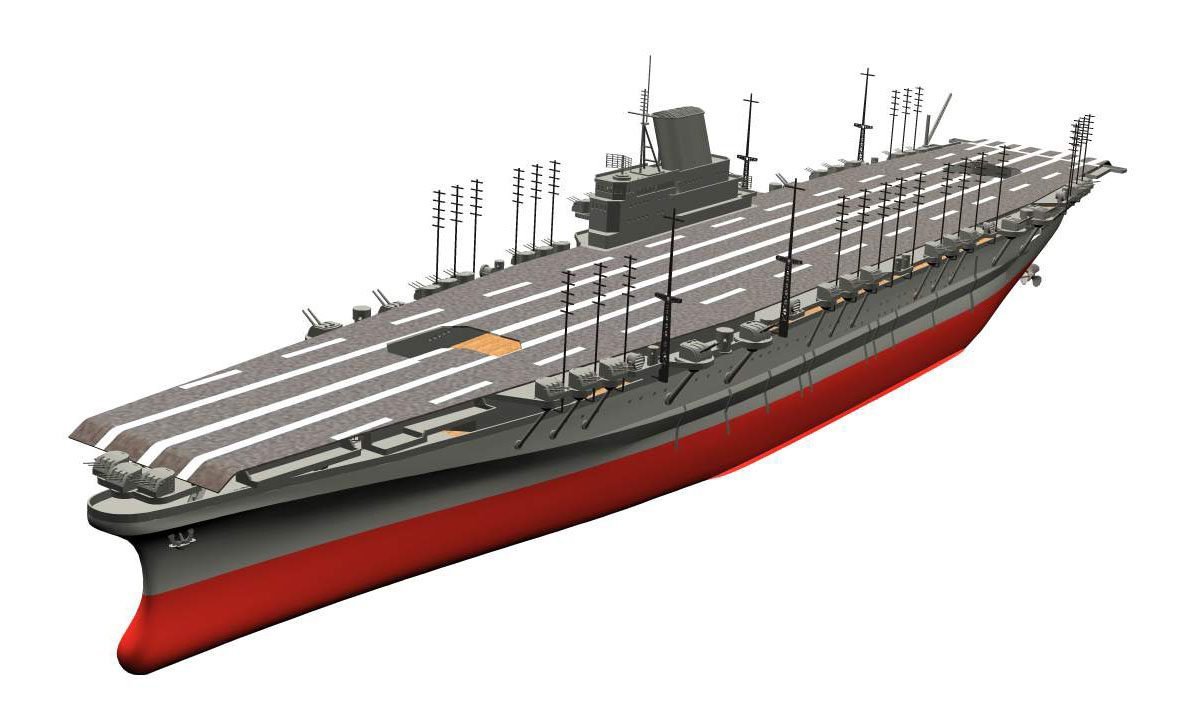

The Allied Fleet for Operation Torch

The landing of 70,000 men between Casablanca and Algiers for Operation Torch required a lot of transports and warships. Six pre- and four attack convoys with a total of 250 vessels from Britain went out into the sea, four more convoys with a total of 136 ships directly from the United States. For the escorts, which were concerned for the security of the convoys, this was a heavy responsibility. Including the artillery support and the command ships for Operation Torch, there were

- 6 battleships,

- 5 fleet carriers,

- 7 escort carriers,

- 15 cruisers,

- 81 destroyers and

- 38 escort vessels

of different types involved. Unfortunately, most of the aircraft carriers and escort vessels had to be withdrawn from the Battle of the Atlantic, where they were bitterly missed in the following months.

The Allied Troops for Operation Torch

The Casablanca landing of Operation Torch was be done by troops coming direct from the United States, while the other two where be mounted from the Clyde in Scotland. The 24,500 and 18,500 Americans landed at Casablanca and Oran respectively would form the US Fifth Army, and be responsible for warding off any possible German or Spanish counter strike through Spain.

The 20,000 Anglo-Americans landed at Algiers would become the British First Army and were to exploit into Tunisia as soon as possible.

It was arranged that the US 12th Air Force should support the Casablanca and Oran landings, while 133rd Group RAF covered Algiers.

The nearest Allied airfield was Gibraltar, and this was in fighter radius of action to Oran only, and then the time possible in the air over the port was so short as to make it uneconomical. Air support during the initial landings would hence have to be reliant on Allied carrier-borne aircraft.

The realization that airfields must be captured quickly so that more effective air support could be provided, brought about a later amendment to the plan. This called for a force of US paratroops to capture the airfields around Oran simultaneously with the landings.

The Western Task Force for Operation Torch was commanded by Maj-Gen George S. Patton, whose name would in a matter of months become synonymous with flamboyance and drive. Under his command were 2nd Armored Division, 3rd and 9th Infantry Divisions, 70th and 756th Tank Battalions, 603, 609, 702 Tank Destroyer Battalions, 36th Combat Engineer Regiment, and two signal companies.

Center Task Force of Operation Torch under Maj-Gen Lloyd Fredenhall was 1st Armored Division and 1st US Infantry Division.

The Eastern Task Force was a mixed Anglo-American force and became on 10 November British First Army. Appointed to command it had been Lt-Gen Anderson. At the outset the troops available to him hardly represented the title ‘Army’, consisting of two British infantry brigades (11 and 36 of 78th Division), a small portion of the British 6th Armored Division and three battalions of the 1st British Parachute Brigade, together with some commandos.

The French reaction in North Africa to Operation Torch

Once on North African soil after Operation Torch, however, the reactions and responses of a third nationality were soon to complicate events, adding to them at the same time a purely Latin flavor of tragicomedy. The American belief that they were so beloved by the French while the British were so hated as to make the essential difference between welcome and resistance in North Africa had already caused unnecessary complications in the tactical planning (in that the landings had to appear to be all-American).

But the French desire, on the one hand to avoid retribution at the hands of the Germans if the landings proved a failure, and on the other to play an important part in their own liberation should they succeed, complicated the situation immeasurably more.

However, by one of history’s oddest twists, the Gordian Knot was cut by the very man who had most reason to hate the British, and good reason to suspect the Americans. Admiral Darlan, the Vichy C-in-C who was visiting the area at that time for purely personal reasons, was one of the few French leaders with the authority to order the French forces to stop their desultory resistance and join the Allies. After some hesitation he ordered a ceasefire on November 10 and the Allies could at last turn their energies to the more important military objectives – the ports of Tunis and Bizerta.

The French forces opposing to Operation Torch

The 1940 armistice had limited the Vichy French forces, named l’ Armee de l’ Armistice, in North Africa to 120,000 men, with 55,000 in Morocco, 50,000 in Algeria and 15,000 in Tunisia. They were for the most part native troops officered by Frenchmen. Although ammunition was short and equipment obsolete, their fighting caliber was high.

During the time of Operation Torch the French Air Force had some 500 aircraft based on five airfields in Morocco, all within easy range of Casablanca, and various other fields in Algeria and Tunisia, which were in easy striking distance of the ports. Although those aircraft were deemed obsolete, the quality of their fighters was better than the Allied carrier-borne types.

In Morocco there were two fighter, two reconnaissance and four bomber groups plus two flotillas of naval aircraft and two transport groups.

In Algeria the Vichy Air Force consisted of three fighter, one reconnaissance and three bomber groups with one flotilla of naval aircraft.

In Tunisia a small presence was maintained by one fighter, two bomber and one reconnaissance group with one unit of naval flying boats.

A group was usually formed from two escadrilles, which normally consist of 12 aircraft.

Of even greater concern was the French naval strength in the area. Although Bizerta and Oran held only submarines and destroyers, there were a 6-inch cruiser, destroyers and an immobile battleship capable of firing its guns at Casablanca, together with a battleship and three cruisers at Dakar.

The fleet in Toulon (Southern France), with its three capital ships, seven cruisers, 28 destroyers and 15 submarines, could also not be excluded from the calculations for Operation Torch.

The Axis reaction to Operation Torch

Shortly after the main landings in Algeria and Morocco, the British 1st Army drove into Tunisia to clear the coastline and link up with the 8th Army, now advancing from El Alamein.

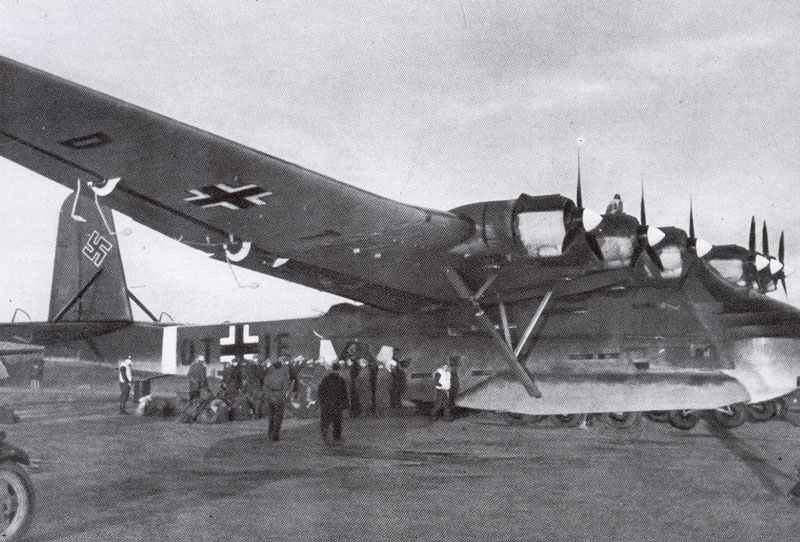

But the swift conquer of Algeria and Morocco had been atypical; in Tunisia the Germans reacted with speed and efficiency, and rapidly built up their forces. Within three days of the Allied landings, German air-lifts were bringing troops and equipment into Tunis, and by the end of the month 15,000 well-armed and experienced German soldiers and 9,000 Italians were expertly deployed to block Allied plans.

By pouring troops into this ‘Tunisian Bridgehead’ Hitler was hoping to prevent or at least delay an Allied attack on Southern Europe. By the end of January 1943 the Axis had over 100,000 troops in Tunisia and had brought the Allied advance to a halt.

The Axis forces opposing to Operation Torch

On November 6, the German Navy expected enemy landings at first at Tripoli and Benghazi, with the second possibility at Sicily, Sardinia or Italy and at least at French North Africa.

There were available nine U-boats in the Western Mediterranean and 10 E-Boats (MTB) at Sicily. The Italian Navy had 26 submarines south of Sardinia, 20 MAS (MTB) at Cape Bone (Tunisia), light cruisers and destroyers at Palermo and Naples. Because of the missing of air cover it was not planned to use Italian capital ships.

After the Allied Operation Torch landings in North Africa, Vichy France applied on the same day (November 8) for German troops and the re-armament of the French Forces. It was planned to use the French fleet in Toulon against the Allied landings. On November 9 a conference between Hitler, Laval (France) and Ciano (Italian foreign minister) was planned at Munich to form an alliance. This was cancelled after the ceasefire by Admiral Darlan in Algiers.

Although the Germans had reacted very quickly to the Operation Torch landings, and indeed seized El Aouina airfield outside Tunis on the 9th, the Allies continued to underestimate the German build-up in Tunisia throughout the early days.

Thus, by mid-November the Axis has landed some 5,000 troops, whereas by the end of the month there were no less than 15,500 troops with 130 tanks under the command of General Nehring, sometime commander of the Afrika Korps, including some of the German’s latest model, the Tiger Tank.

Additional, during the early days of the campaign the Axis air forces retained air superiority. Allied airfields were far from the front, and for the most part were not all-weather, which meant that when the winter rains came at the end of November they would become virtually inoperable.

The Axis, on the other hand, had good airfields close to the front, with the added capability of being able to fly sorties from Sardinia, Pantelleria and Greece, as well as relatively easy lines of communications from Sicily and Italy.

The rush to Tunisia

At the time of Operation Torch at the other end of the Mediterranean, Rommel was also meanwhile heading for Tunisia. Four days before the Torch landings took place, the Axis defenses at El Alamein had finally given way and the 8th Army began the last pursuit of the Afrika Korps – who with typical efficiency succeeded in fighting repeated and stubborn rear guard actions despite their exhaustion and lack of supplies.

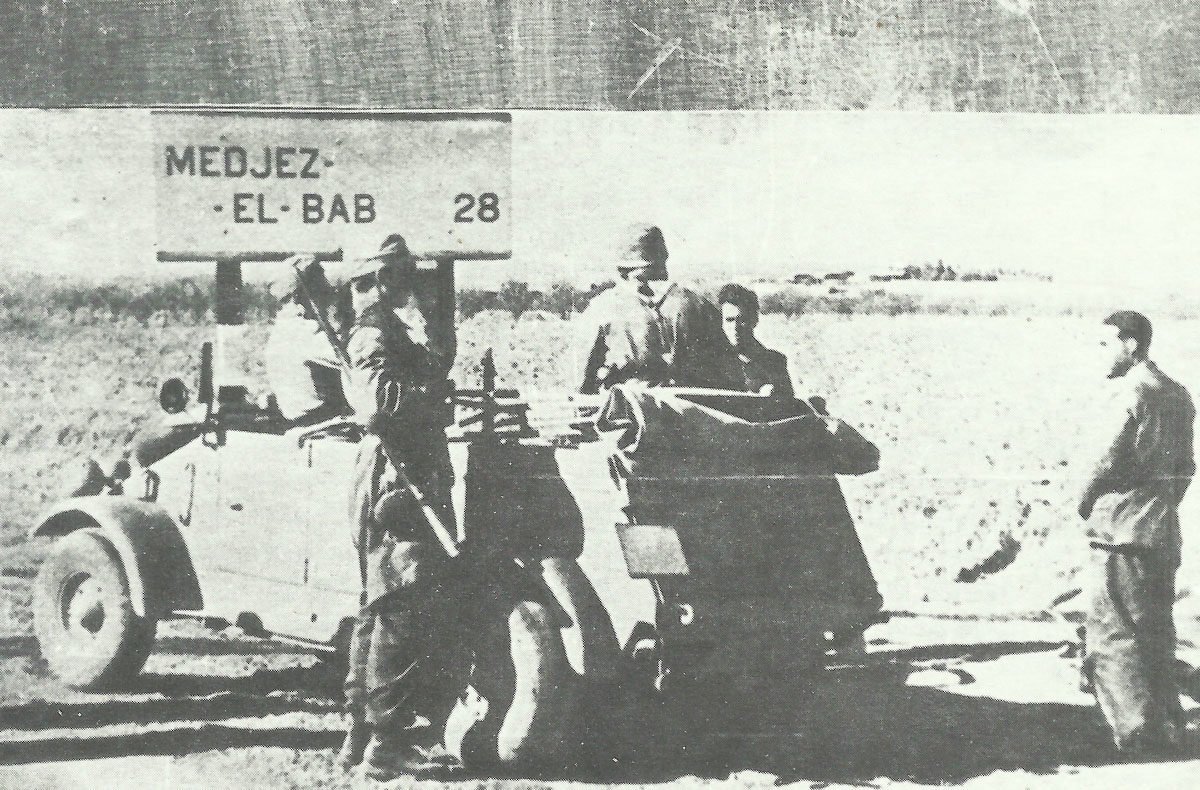

One of the weaknesses of the Torch planning was that no provision had been made to neutralize Tunisia during the initial stages. German reaction was faster than Allied planners had thought possible, and a race developed between the British 1st Army and the German advance parties – first to seize certain vital airfields with airborne troops, and then to occupy the passes leading into the Tunisian plain with orthodox forces.

The Allies won the first lap, but their advance towards Tunis and Bizerta was stopped by the Germans on a line running from Oudna through Tebourba towards Mateur. By this time, the 1st Army had outrun its supply lines and lacked the impetus to break through the German defenses.

Meanwhile, the Germans and Italians continued their build-up, pouring in troops and aircraft. The prime German deficiency was in artillery: guns of all types numbered less than 40, but operations were in fact hardly hampered – the Ju 87 Stukas provided intense fire-support by day and the mortars were a deadly supplement.

It was the mountainous terrain, however, which most aided the Axis defense.

References and literature

Der 2. Weltkrieg (C. Bertelsmann Verlag)

Zweiter Weltkrieg in Bildern (Mathias Färber)

A World at Arms – A Global History of World War II (Gerhard L. Weinberg)

Der Grosse Atlas zum II. Weltkrieg (Peter Young)

Historical Atlas of World War Two – The Geography of Conflict (Ronald Story)

The Desert War (Andrew Kershaw, Ian Close)

The Tunesian Campaign (Charles Messenger)

I am trying to establish if it is at all possible to get consent to use images and maps from the Tunisian Campaign WWII 1942- 1943.

I am in the process of researching and compiling a book and to overcome copywrite issues I need to get consent to use images.

Can you help me? As I have a number of battle images and maps to look for.

Kind regards,