The Siege of Tobruk, from April to December 1941 (Part II).

Rommel’s attack on the defensive perimeter, trench warfare and the circumstances get worse at Tobruk.

Rommel’s attack on the defensive perimeter of Tobruk

Table of Contents

Opposed to the backcloth of coastal sea and air struggle, the battle on land muttered and grumbled between bombardments and patrol-scuffles while Rommel, chastened by his first rebuffs, increased his forces for a total attack. He had been changing into eager. Virtually any strike across the Libyan-Egypt border was impossible before Tobruk had been captured, however he wasn’t prepared before April 30.

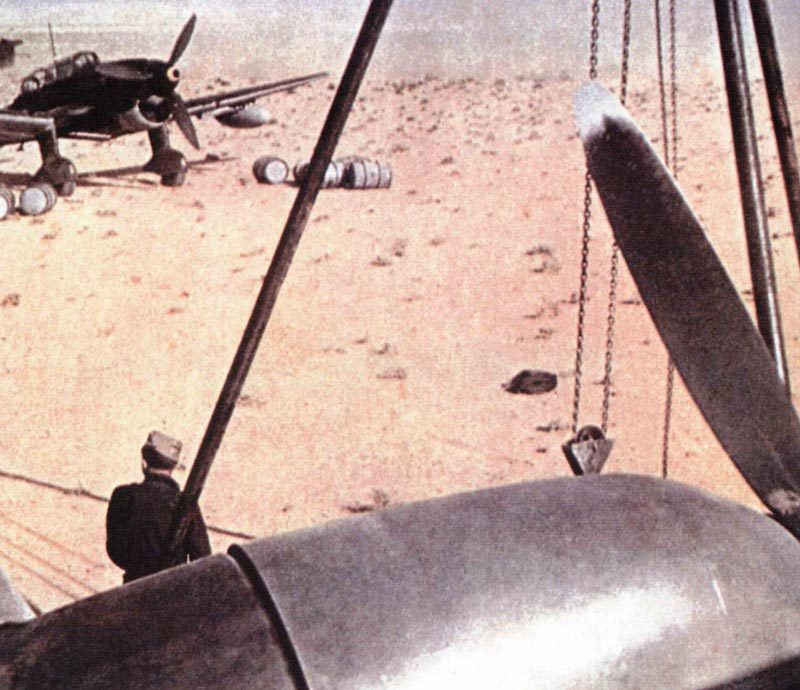

The assault on that day started with a continuous dive-bombing attacks by Ju 87 Stukas and hammering from guns, against which the defenders’ capabilities of retaliation were restricted. They were firing on the dive-bombers with anti-aircraft and small-arms, and the British artillery presented counter-fire on the Axis artillery positions. But due to the fact the garrison couldn’t count on new resources of ammo before the following moonless night – 7 days in front – rounds had to be husbanded and each shot meant to calculate.

The German dive-bombers had been unchallenged over Tobruk, for the Royal Air Force Hawker Hurricane fighters, not able to operate from airstrips under ongoing shelling – with the runways commonly cratered along with workshops and petrol-dumps hit day by day – had been removed on April 25.

It had been a severe and nasty struggle. Writing of it afterwards Rommel mentioned: ‘The Australians battled with outstanding tenacity. Furthermore, their injured continued defending themselves with small-arms fire, and even continued in the struggle to their final breath. These folks were incredibly huge and robust guys, who undoubtedly symbolized an elite unit of the British Empire, an undeniable fact that seemed to be obvious in combat.’

After the day the Germans and Italians had been successful in, breaking through the defenses of Tobruk and had created a two-mile salient into the Australian positions on the western area of the perimeter. The salient incorporated the key hill of Ras el Madauar, which overview most of the defended section.

Still going to capture Tobruk, Rommel following day send in new soldiers, to take advantage of the Ras el Madauar salient, however despite the fact that the battle went on unchecked until May 4, the Axis troops could not strike deeper.

The salient of Ras el Madauar, nevertheless, continued to be a steady danger to the surrounded garrison and – even though there had been occasional fights on the other areas of the defended perimeter – from May 4 onwards the defense of Tobruk was, generally, the defense of the western area. There the tough covering of stable defense works had been violated, and the rival troops confronted each other from quickly improvised foxholes. It had been, you might say, the soft under-belly of Tobruk: the Axis troops thought that if the breakthrough occurred at any place it would happen at the western area, and this was the spot to which they focused many of their effort.

Trench warfare around Tobruk

The moment Tobruk have been under siege for 4 weeks the vicinity surrounding the city had been full of burned-out tanks, trucks, as well as almost all the rubbish of warfare. The city itself had been lowered to a pile of dirt where just one building still existed, and inside this – regardless that it separated itself among the destroyed houses like a sore thumb – General Morshead set up his operational HQ.

For the Allies in Tobruk day after day launched a brand-new collection of troubles. Issues, that is definitely, besides those typically involved with desert fighting – the bizarre confusion a result of a featureless scenery which caused a habit to run in circles; and day-to-day temperatures in the 100s, so that to touch a tank placed in the sunshine resulted in a burned hand. There were difficulties of food; not really a deficiency, perhaps, however a boring sameness with everything taken from cans. There was, similar to other places in the desert, a lack of drinking water, and what tiny there was had been salty. There seemed to be a virtually complete lack of bread, and too many of bugs, rats and flies.

Combined with these pains was a difficulty uncommon in the history of defended strongholds. The German and Italian airfields from which sorties were done towards Tobruk had been very close for the defenders to listen to the planes setting up just before take-off. A couple of the airfields, El Adem and Acroma, had been approximately Ten miles away, and several of the Allied soldiers promised that in the still, desert night atmosphere they were able to listen to the Axis ground staffs singing as they handled the planes.

There would be just one single stable kind of protection resistant to the bombers after the Royal Air Force Hawker Hurricanes have been taken out on April 25, which had been the anti-aircraft guns of the Royal Artillery, supplemented by the weapons of vessels in the port. A pair of regiments of 3.7-inch AA-guns in addition to captured Italian 102-mm weapons, additionally 3 regiments of 40-mm Bofors remained for the entire siege, firing their guns against each new air strike by high-level and dive-bombers.

During numerous air attacks the gunners copied their buddies at The island of Malta by maintaining a little ‘Grand Barrage’ when confronted with the severe courage of German aviators who in some cases swept below Five-hundred feet above the weapon positions. From July the dive-bombers definitely started to decrease their missions, and it turned out to be practical even to unload vessels in daytime. On its own, the anti-aircraft gunners stopped bombing with impunity, and so they, most importantly, allowed the y ships to unload and supply the garrison.

The western area, surrounding the Ras el Madauar breakthrough, found unique problems. The rugged character of the land made deep digging extremely hard and, on those times when the battle took not really occurring, each side lay inside their low ditches not able to move. A German story about the situations within the salient during that time states: ‘The Aussies had been trained shooters. Their sniping had been outstanding. Perhaps simplest motion in the foxhole – rump too excessive – and ping ! You would have it.’

For night patrols, the Australians used crepe-soled footwear, lengthy trousers, Berets and pullovers. They were equipped with sub-machine guns and grenades, and their aim typically would be a solitary axis stronghold. They would infiltrate into it quietly on a moonless night, throw their grenades and fire the magazines of the sub-machine guns into the opponent position, after that disappear straight into their own trenches as fast and softly as they had appeared.

The German soldiers utilized quite similar method opposed to the Australians and British, and on situations a patrol from each side could face each other in No-Man’s-Land, along with a brief rough combat could occur, often related to wild, hand-to-hand battling.

Circumstances get worse at Tobruk

As time continued, circumstances within the besieged place grew to become gradually worse, a reality of which Rommel himself had been extremely sensitive. Writing home to his wife in June he stated: ‘Water is extremely limited in Tobruk, the British soldiers are receiving just half-a-liter per day. Using our dive-bombers I am hoping to be able to, reduce their rations even more. The temperature is becoming more painful each day and … a person’s thirst becomes nearly unquenchable.’

Churchill, as well, had been very sensitive to the significance of Tobruk, as well as the function it must and might participate in the Western Desert strategy. After Tobruk had successfully survived one of the several assaults by the Axis troops, he sends a message: ‘Bravo, Tobruk ! We’re feeling it essential that Tobruk should be regarded as the sally harbour.’

This the Australians and British soldiers managed, despite the fact that commonly their fights were overshadowed by incidents somewhere else. The big news came from the airborne assault on Crete, the German invasion on Russia, as well as – considerably closer to the beleaguered garrison – the abortive Operation ‘Battleaxe’. In spite of this, the Australian and British soldiers in Tobruk carried on to be a crucial component in the strategic actions of both sides in the Western Desert.

to Part II: Siege of Tobruk ends