The development of the atomic bomb, the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and Japan’s surrender in 1945: origins, effects, and legacy.

Table of Contents

World War II hit its breaking point in August 1945 when the United States dropped atomic bombs on two Japanese cities. That act changed the course of human history in a way that’s hard to overstate. The bombings of Hiroshima on August 6 and Nagasaki on August 9 killed somewhere between 150,000 and 246,000 people. These attacks marked the first and only use of nuclear weapons in war.

The choice to use atomic bombs came after years of scientific breakthroughs and tense military planning. American leaders faced the grim possibility of invading Japan, which would have cost countless lives, so they turned to the new nuclear weapons instead. “Little Boy” hit Hiroshima with the force of 15,000 tons of TNT, and “Fat Man” hammered Nagasaki three days later with even more power.

The atomic bombings still spark debates about military necessity, civilian deaths, and moral responsibility. The events of August 1945 totally transformed international politics and made nuclear weapons a central part of modern warfare. To really grasp this turning point, you have to dig into the science, the military strategies, and the political decisions that led to these devastating attacks and Japan’s surrender.

Key Takeaways

- The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 killed over 150,000 people and forced Japan’s surrender six days later

- These attacks represented the culmination of the secret Manhattan Project and marked the first use of nuclear weapons in human history

- The bombings ended World War II but created lasting debates about nuclear warfare and fundamentally changed global politics

The Road to Nuclear Warfare: Scientific and Military Context

The atomic bomb didn’t just appear out of nowhere—it grew out of scientific breakthroughs and deep fears about Nazi Germany’s nuclear ambitions. The Manhattan Project pulled together top scientists and military leaders to build the first nuclear weapons.

Fears of Nazi Germany’s Atomic Program

German scientists made big nuclear discoveries in the late 1930s. Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann achieved nuclear fission in 1938. That news rattled Allied scientists, who knew Germany had serious research muscle.

Albert Einstein wrote to President Roosevelt in 1939, warning him that Germany might build atomic weapons first. His letter made it clear the U.S. needed to get moving on nuclear research.

Intelligence reports hinted that German scientists were pushing ahead with nuclear projects. The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute had top physicists working on atomic energy. Werner Heisenberg ran Germany’s nuclear program during the war.

Allied leaders worried that a Nazi atomic bomb could flip the war’s outcome. That threat spurred the United States to launch its own nuclear weapons project. The atomic arms race was on.

The Formation of the Manhattan Project

The United States kicked off the Manhattan Project in 1942. General Leslie Groves took command of this sprawling military operation. The government threw unlimited funds and top priority at the project.

They set up three main sites for different tasks:

- Los Alamos, New Mexico: Bomb design and assembly

- Oak Ridge, Tennessee: Uranium enrichment

- Hanford, Washington: Plutonium production

At its peak, the project employed over 130,000 workers. Most folks had no idea what they were actually building. Security was airtight everywhere.

Key Scientists and Leaders

J. Robert Oppenheimer ran the Los Alamos lab, wrangling the scientific work behind building the bombs themselves. He pulled in some of the world’s best physicists for the mission.

Major figures included:

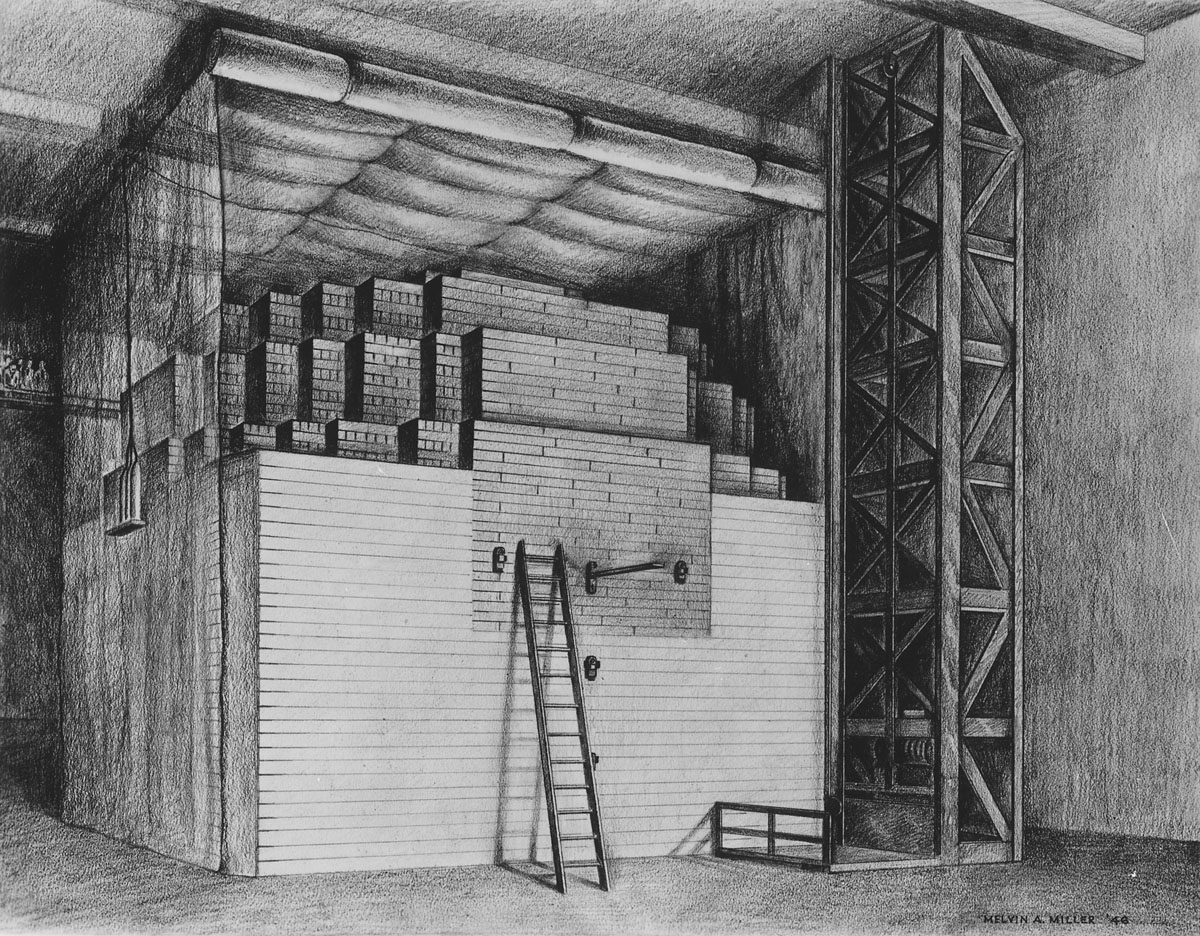

- Enrico Fermi: Built the first nuclear reactor

- Edward Teller: Worked on bomb design

- Leo Szilard: Helped get the project started

- Ernest Lawrence: Developed uranium separation methods

General Groves managed the whole operation, making key decisions on resources and security. He and Oppenheimer worked together despite coming from very different worlds.

The scientists came from all over, including a lot of European refugees who’d escaped Nazi persecution. They brought essential nuclear physics knowledge to the U.S.

The Trinity Test and Final Preparation

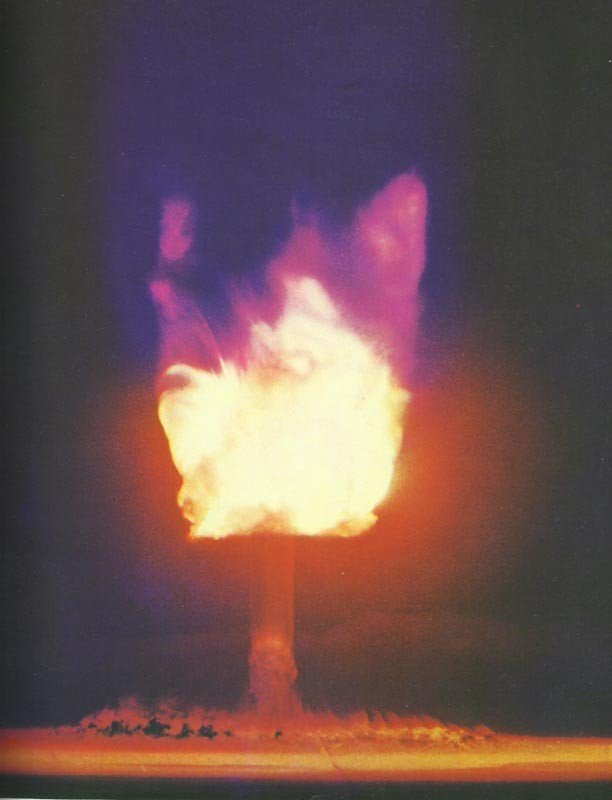

The first atomic bomb test happened on July 16, 1945. The Trinity test went off in the New Mexico desert near Alamogordo. Scientists honestly weren’t sure if the bomb would even work.

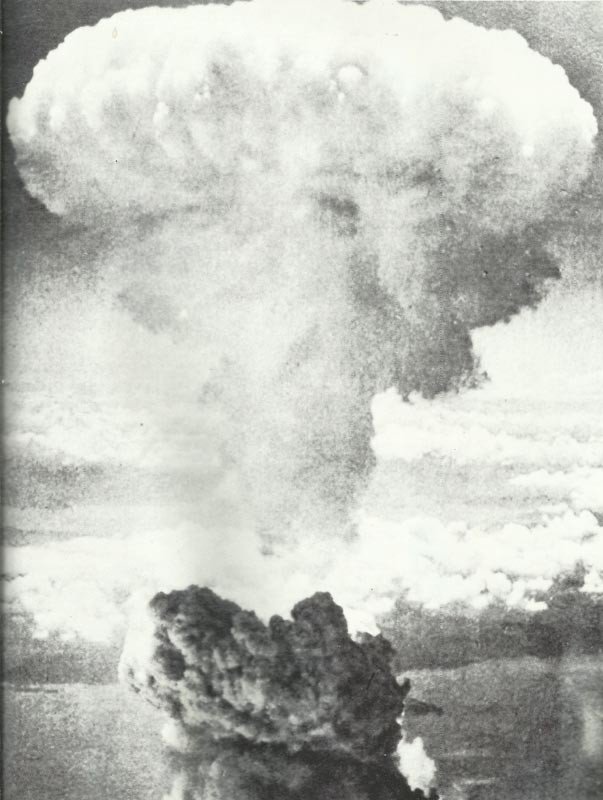

The plutonium bomb exploded with a force equal to 20,000 tons of TNT. It created a massive fireball and a towering mushroom cloud. That test showed atomic weapons were ready for real use.

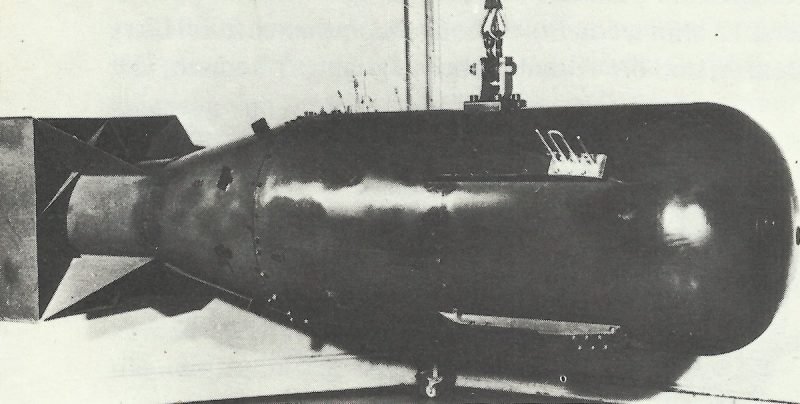

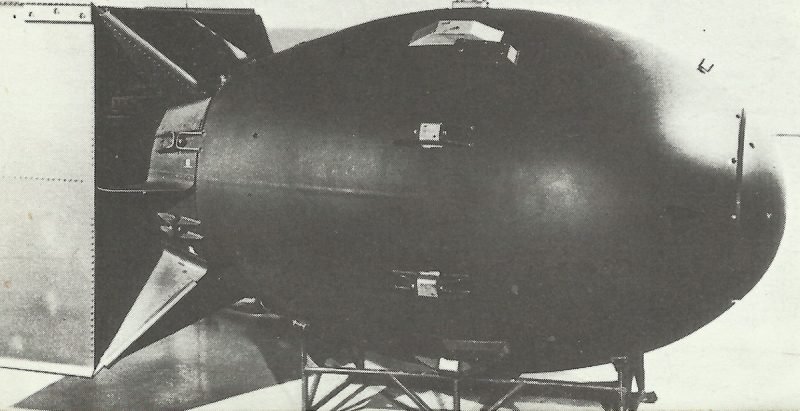

They prepped two bomb designs for Japan:

- Little Boy: Uranium bomb for Hiroshima

- Fat Man: Plutonium bomb for Nagasaki

Oppenheimer watched the Trinity explosion, feeling a mix of awe and dread. He later quoted ancient texts about the sheer destructive power they’d unleashed. The nuclear age was suddenly very real.

President Truman heard about the successful test while meeting with Allied leaders. The U.S. now had the most powerful weapon ever built. Military planners rushed to get everything ready for using atomic bombs against Japan.

Prelude to the Bombings: The Endgame in the Pacific

By early 1945, Japan was feeling the squeeze as Allied forces closed in from nearly every direction. The brutal battles at Iwo Jima and Okinawa showed just how far Japan would go to defend its homeland. The Allies issued the Potsdam Declaration with clear surrender terms, but Japan didn’t budge at first.

Japanese Resistance and the Pacific War

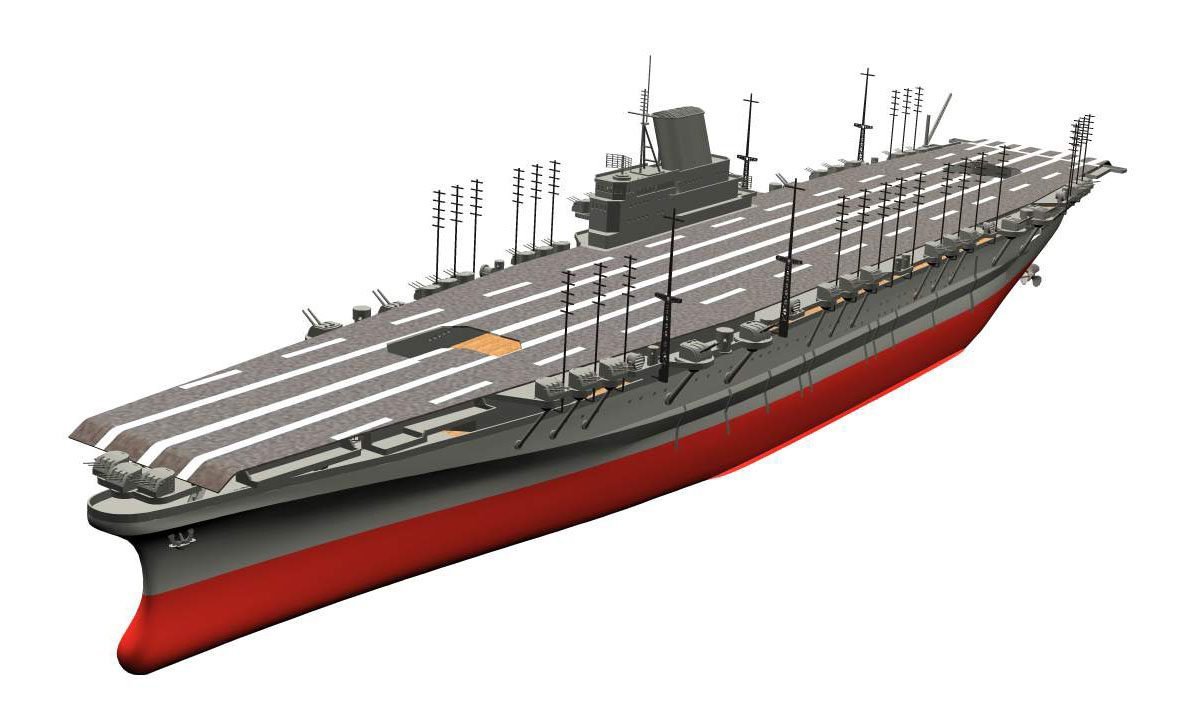

Japan’s military leaders refused to quit, even as the odds turned hopeless in 1945. The country had lost most of its territory and its navy was basically finished.

Japanese forces decided to make any Allied invasion of the main islands as bloody as possible. They hoped this would convince the Allies to offer better surrender terms.

The military set up dense defensive positions all over the home islands. Civilians got training in basic combat and makeshift weapons.

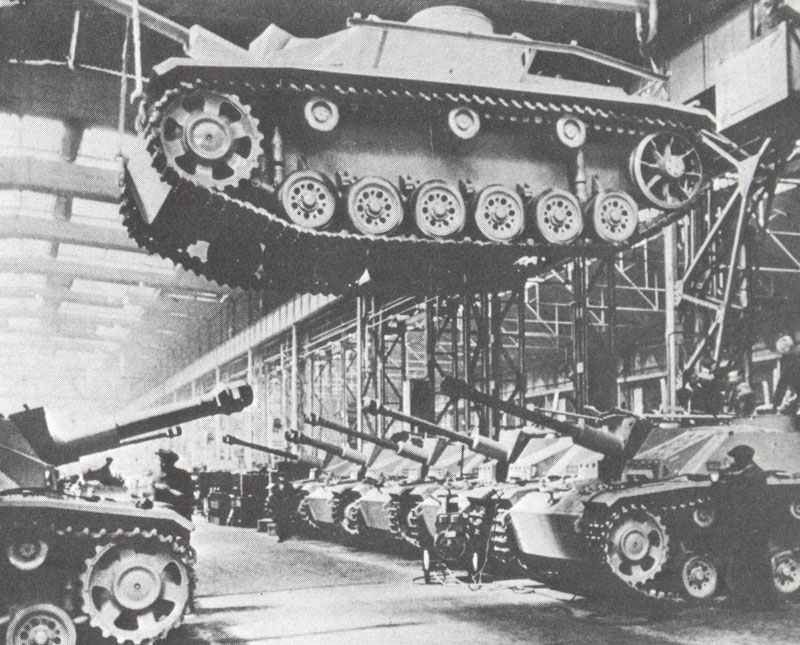

Despite relentless bombing of factories, Japan kept its war production going. The government clamped down on information to keep people from losing hope.

Key aspects of Japanese resistance:

- Refusal to consider unconditional surrender

- Preparation for homeland defense

- Continued military production

- Civilian mobilization programs

The Battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa

Iwo Jima and Okinawa really drove home to American leaders how brutal an invasion of Japan could get. Both battles caused staggering casualties on both sides.

Iwo Jima (February-March 1945):

- 7,000 American deaths

- 18,000 Japanese deaths

- 36 days of fighting for a tiny island

Okinawa (April-June 1945):

- 12,000 American deaths

- 100,000 Japanese military deaths

- 100,000 civilian deaths

The fanatical resistance at Okinawa especially worried Allied planners. Japanese troops used kamikaze attacks and fought to the last man.

These battles made President Truman think hard about how to end the war. Military estimates claimed invading Japan could cost up to a million American lives.

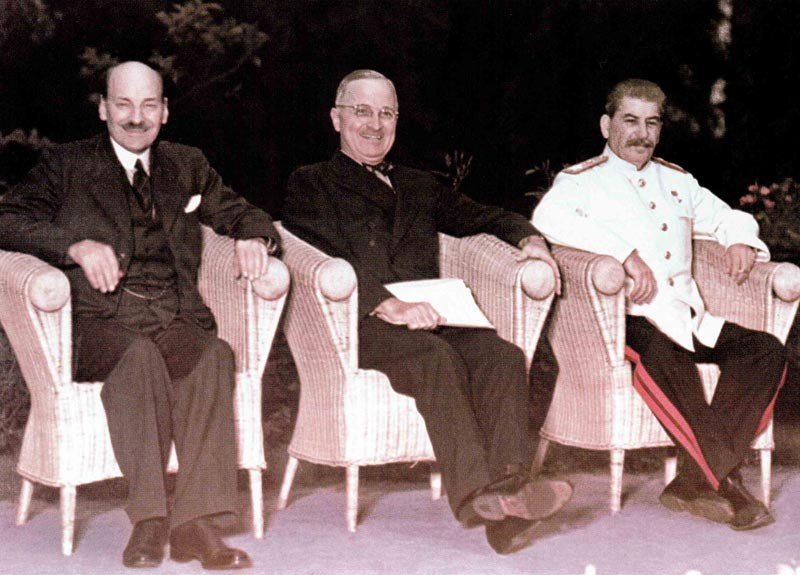

The Potsdam Declaration and Allied Strategy

On July 26, 1945, the United States, Britain, and China issued the Potsdam Declaration. It demanded Japan’s unconditional surrender and spelled out terms for postwar Japan.

The declaration promised Japan wouldn’t be wiped out as a nation. It also guaranteed basic rights for Japanese people after surrender.

Japan’s government rejected the declaration on July 28. Leaders there hoped the Soviet Union might help them get better terms.

President Truman was under pressure to end the war fast. U.S. military leaders started planning Operation Downfall, an invasion of Japan set for November 1945.

The Soviet Union stayed out of the Pacific war until August 8. Stalin had agreed to join the fight against Japan three months after Germany’s defeat.

The Bombing of Hiroshima

On August 6, 1945, the United States dropped the atomic bomb “Little Boy” on Hiroshima. This was the first time anyone used nuclear weapons in war. The Enola Gay, flown by Colonel Paul Tibbets, carried out the mission, killing over 80,000 people instantly and wiping out most of the city center.

Target Selection and Mission Planning

Military leaders picked Hiroshima as the main target for a few reasons. The city held key military facilities and was a major port for Japanese forces. Hiroshima had about 350,000 people and hadn’t been hit hard by earlier bombing raids.

The Target Committee looked at four possible cities: Hiroshima, Kokura, Niigata, and Nagasaki. They wanted urban areas with military value that would really show off the bomb’s power.

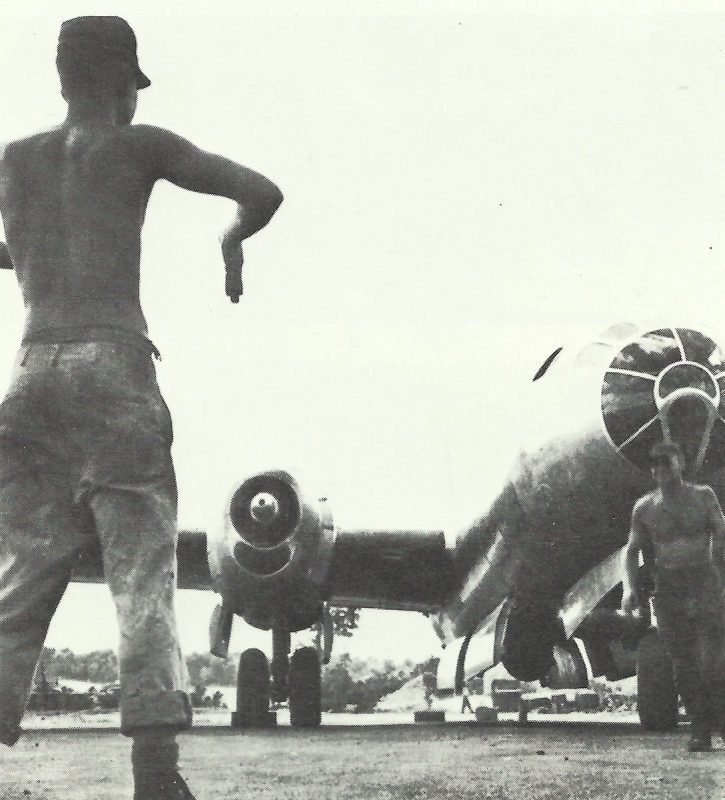

Colonel Paul Tibbets led the 509th Composite Group, the special unit trained for atomic missions. His crew spent months practicing with conventional bombs that matched Little Boy’s size and weight.

The mission needed perfect weather for a visual drop. Planners aimed for early August, hoping for clear skies over Japan.

The Dropping of Little Boy

The Enola Gay took off from Tinian Island at 2:45 AM on August 6, 1945. Colonel Tibbets piloted the B-29 bomber with a crew of twelve, including co-pilot Robert Lewis.

They carried Little Boy, a uranium bomb weighing about 9,700 pounds. The bomb was 10 feet long and 28 inches wide—huge by any standard.

At 8:15 AM local time, the Enola Gay released Little Boy over Hiroshima from 31,060 feet up. The bomb exploded 43 seconds later, about 1,900 feet above the city.

The crew felt the shock wave and could see the explosion from miles away. They banked the plane hard to escape the blast and radiation, barely believing what they’d just unleashed.

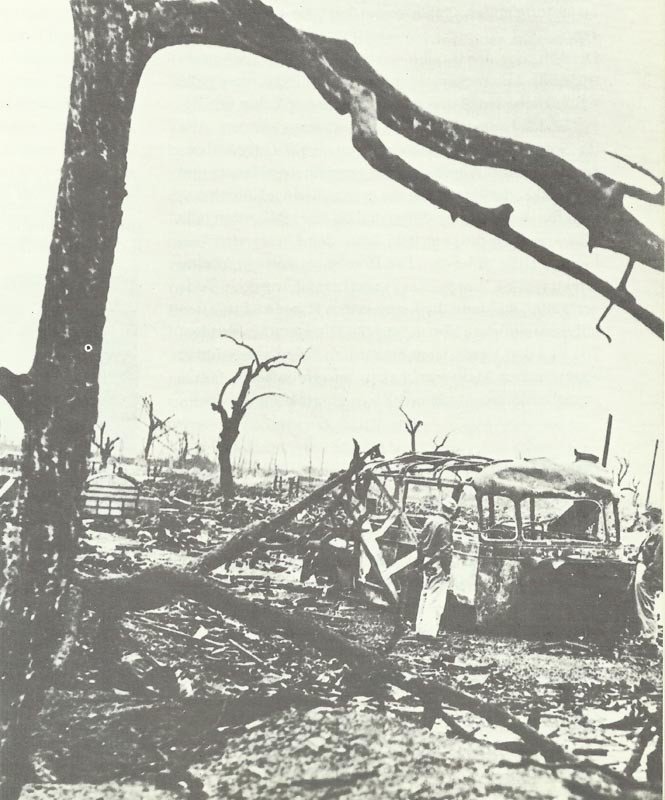

Immediate Effects and Destruction

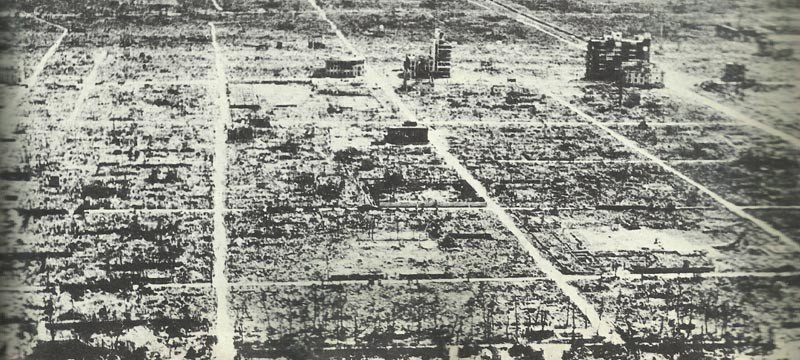

Little Boy exploded and formed a fireball hotter than 7,000 degrees Fahrenheit. That heat vaporized people within half a mile and burned many others up to two miles away.

The blast killed somewhere between 80,000 and 146,000 people by the end of 1945. Most died instantly from the explosion, heat, or radiation.

The bomb wiped out about five square miles of Hiroshima’s center. Nearly 63,000 buildings either collapsed or suffered heavy damage.

The Atomic Bomb Dome still stands, oddly enough. Its steel frame survived because the bomb detonated almost right above it.

Survivors struggled with radiation sickness, burns, and injuries. Many passed away in the following weeks or months as doctors tried to understand what radiation had done to them.

The Enola Gay Crew and Eyewitness Accounts

Captain Robert Lewis, the co-pilot, scribbled in his log: “My God, what have we done?” The crew stared as the mushroom cloud climbed more than 40,000 feet into the sky.

Tail gunner Bob Caron snapped photos of the blast. He saw fires racing through the city and even smelled smoke from their high altitude.

People on the ground saw a blinding flash and felt the heat slam into them. Some remembered seeing shadows burned right into concrete where people had stood.

Dr. Michihiko Hachiya, a local doctor, filled his diary with medical details. He treated thousands with burns and radiation symptoms that no one had ever seen before.

The Enola Gay made it back to Tinian after a 12-hour flight. News quickly reached President Harry Truman, who was still traveling home from Europe.

The Bombing of Nagasaki

Three days after Hiroshima, the U.S. dropped another atomic bomb—this one called “Fat Man”—on Nagasaki, August 9, 1945. The mission didn’t go smoothly; clouds forced the crew to switch from Kokura to Nagasaki, and the bombing created a new generation of survivors, the hibakusha.

From Kokura to Nagasaki: Change of Target

The B-29 “Bockscar” took off at 3:49 AM with Major Charles Sweeney at the controls. Their first destination: Kokura.

Kokura was picked because of its huge munitions plant. Military planners saw it as a key target for the second bomb.

When Bockscar reached Kokura, the city was hidden by thick clouds and smoke. Fires from earlier raids on Yawata filled the air.

Three Failed Attempts

- First bomb run: Target lost in clouds

- Second bomb run: Still no visual

- Third bomb run: Antiaircraft fire started to get too close

Bombardier Kermit Beahan never got a clear look at the target. The crew circled for nearly an hour, hoping for a break in the clouds.

Fuel started running low, so Sweeney decided they had to try Nagasaki instead. The switch wasn’t part of the original plan—it was desperation.

The Dropping of Fat Man

Bockscar reached Nagasaki about twenty minutes later. Clouds covered downtown Nagasaki too, just their luck.

The crew thought about dropping the bomb by radar. Weaponeer Frederick Ashworth suggested it when it looked like they’d never see the target.

At the last minute, a gap opened in the clouds. Beahan spotted a landmark and guided the bomb run by sight, with only three minutes to spare.

Fat Man Details:

- Weight: 10,800 pounds

- Type: Plutonium implosion bomb

- Yield: 21 kilotons of TNT

- Drop time: 10:58 AM local time

The bomb fell for 43 seconds before it exploded. It went off 1,650 feet above the ground and landed about 1.5 miles off target.

The blast hit the Urakami Valley. That spot, surrounded by hills, ended up limiting the destruction a bit compared to a city-center hit.

Destruction and Casualties

The explosion flattened everything within a mile. Fires tore through the northern part of Nagasaki, burning two miles south from ground zero.

Most buildings in Nagasaki were old-style Japanese homes. Wood frames and tile roofs didn’t stand a chance against the blast.

Immediate Impact:

- Almost every building in the blast radius destroyed

- 40,000 to 75,000 people killed instantly

- 60,000 badly injured

- About 263,000 people lived in the city that day

The Urakami Valley’s hills absorbed some of the blast. Geography saved parts of the city from total ruin.

Many residents had already evacuated to rural areas before August 9. Earlier bombings had scared people away and shrunk the population.

The bomb wiped out the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works and the Mitsubishi-Urakami Ordnance Works. Both were major military factories.

Long-Term Effects on Survivors

Survivors in Nagasaki became known as hibakusha—Japanese for “explosion-affected people.”

By the end of 1945, total deaths reached about 80,000. Many died later from radiation sickness or burns.

Long-term Health Problems:

- Radiation-linked cancers

- Blood disorders

- Genetic effects in children

- Chronic illnesses

Hibakusha dealt with discrimination for decades. Employers and families often avoided them, scared of radiation’s effects.

These survivors became witnesses to nuclear war. Their stories made the world face the real cost of atomic bombs.

Doctors and scientists still study hibakusha today. Their experiences keep teaching us about radiation’s impact on health, even now.

Aftermath and Japan’s Surrender

The bombings triggered a medical crisis from radiation exposure. Emperor Hirohito announced Japan’s surrender on August 15, 1945.

The formal end of World War II came on September 2, 1945, aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay.

Radiation Sickness and Medical Impact

Radiation sickness hit survivors in ways doctors had never seen. Symptoms showed up within days.

People suffered nausea, vomiting, and burns. Hair fell out, bleeding started, and some who seemed okay at first grew sick weeks later.

Radiation Effects Timeline:

- First 24 hours: Burns and immediate injuries

- 1-4 weeks: Hair loss, bleeding, infections

- Months later: Cancer and long-term health problems

Medical workers had no idea how to treat radiation sickness. They lacked medicines and most hospitals were in ruins.

The U.S. set up medical programs for survivors and started studying radiation’s effects. That research eventually shaped nuclear medicine.

Children suffered the most from radiation. Many developed leukemia in the years that followed, and birth defects rose among babies born to exposed mothers.

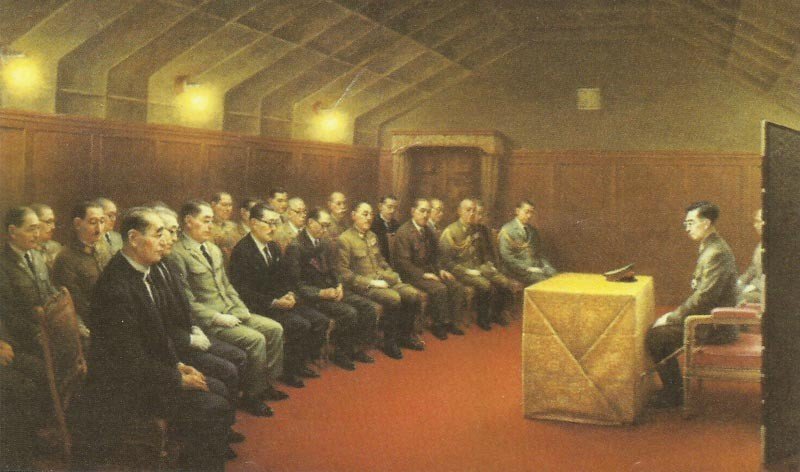

Emperor Hirohito’s Announcement

On August 15, 1945, Emperor Hirohito declared Japan’s surrender, six days after Nagasaki. His speech went out on the radio at noon.

He spoke in formal language, and many people struggled to understand him. He said Japan would “endure the unendurable” and accept the surrender terms.

Hirohito referred to the enemy’s “new and most cruel bomb.” He warned that fighting on would mean “total extinction of human civilization.”

The announcement shocked soldiers and civilians. They’d been taught surrender was shameful. Some military leaders even tried to stop the broadcast.

The Soviet Union’s sudden attack on Japanese-held territory in China pushed leaders closer to surrender. Facing defeat on two fronts, Japan had no good options left.

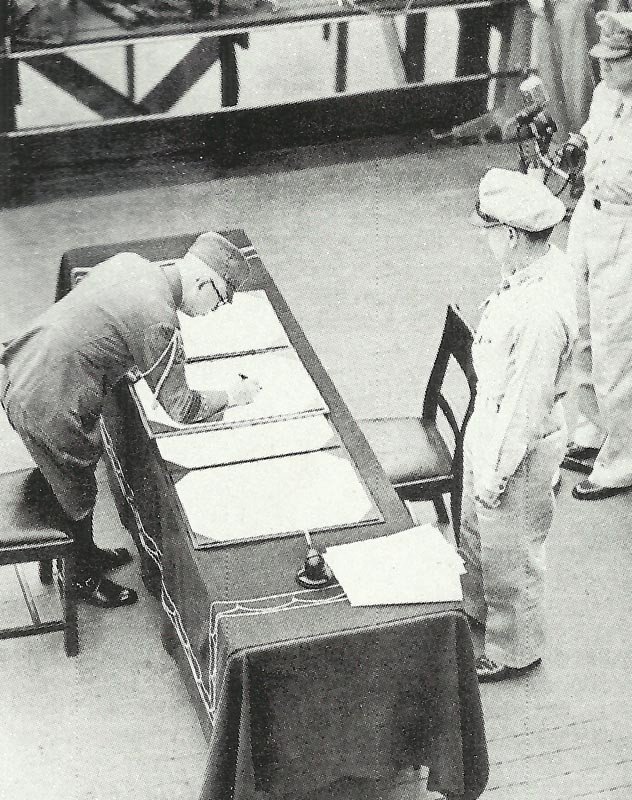

Formal Surrender on USS Missouri

Japan’s formal surrender happened September 2, 1945, aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay. General Douglas MacArthur accepted on behalf of the Allies.

Foreign Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu signed first for Japan. General Yoshijiro Umezu signed for the military.

The whole ceremony took about 20 minutes. Representatives from Allied nations watched as the surrender became official.

MacArthur spoke about building a peaceful world after so much destruction. He said the victory belonged to all the Allies, not just the U.S.

Key Participants:

- For Japan: Shigemitsu, Umezu

- For Allies: MacArthur, Admiral Nimitz

- Witnesses: Delegates from Britain, China, the Soviet Union, and others

The surrender terms let the U.S. occupy Japan. American forces oversaw Japan’s transition to democracy under MacArthur’s leadership.

Legacy and Global Impact

The atomic bombings still fuel debate over nuclear weapons and ethics. They also kicked off the global arms race and shaped Cold War tensions. Memorials in Japan and elsewhere try to keep the memory—and the warning—alive.

Ethical and Strategic Debates

The bombings raised tough questions about using atomic weapons on civilians. Even military leaders argued over whether the bombs were really needed to end the war.

Some said the bombs saved lives by avoiding a bloody invasion. Others figured Japan was already on the verge of surrender.

Key ethical concerns:

- Bombing cities instead of military targets

- Testing new, unproven weapons on people

- Were there other ways to force surrender?

John Hersey’s 1946 New Yorker article “Hiroshima” changed public opinion. For the first time, Americans read about the suffering caused by the bombs.

After that, people started seeing atomic weapons less as scientific marvels and more as instruments of devastation. By late 1945, some 200,000 Japanese civilians had died from the bombings.

The Beginning of the Cold War and Nuclear Arms Race

The atomic bombings kicked off a nuclear arms race between the U.S. and Soviet Union. That competition shaped the Cold War for decades.

The Soviets tested their first atomic bomb in 1949. Both sides then built thousands of nukes, each more powerful than the last.

Cold War nuclear developments:

- Hydrogen bombs in the 1950s

- Intercontinental missiles

- Nuclear submarines

- Multiple warhead systems

The arms race made nuclear war a constant fear. Kids practiced duck-and-cover drills in school. Some families even built fallout shelters in the backyard.

The Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 almost brought the world to nuclear war. That close call showed just how dangerous atomic weapons had made things.

Movies and TV shows reflected these fears—radiation monsters, doomsday stories, all that. The idea of “mutually assured destruction” hung over politics and culture for a long time.

Commemoration and Memory

Japan put up memorials to honor bombing victims and push for peace. The Atomic Bomb Dome in Hiroshima got UNESCO World Heritage status in 1996.

The hibakusha (atomic bomb survivors) started sharing their stories to help people understand nuclear weapons’ effects. They dealt with radiation sickness and even discrimination for years.

Major memorial sites include:

- Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park

- Nagasaki Peace Park

- Memorial museums in both cities

- Annual peace ceremonies on August 6 and 9

The bombings seeped into Japanese pop culture, too. Godzilla, for example, became a symbol of nuclear destruction and the fears around radiation.

Right now, there are about 13,890 nuclear weapons worldwide. The United States, Russia, and the United Kingdom hold most of them.

Frequently Asked Questions

The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, 1945, were the first—and so far only—times nuclear weapons were used in war. These events involved all kinds of military decisions, killed over 150,000 people almost instantly, and shaped international relations after the war in ways that still linger.

What factors led to the decision to use atomic bombs against Japan?

American military leaders wanted to avoid a brutal invasion of Japan. Operation Downfall, the planned invasion, would have meant hundreds of thousands of American casualties and millions of Japanese deaths.

Japan showed fierce resistance throughout the Pacific War. At Iwo Jima, almost every defender fought to the death. At Okinawa, 94 percent of the 117,000 Japanese soldiers died rather than surrender.

The United States suffered nearly a million casualties in the war’s final year. American reserves were running thin, and people at home wanted soldiers back.

Japan ignored the Potsdam Declaration on July 26, 1945. This ultimatum demanded unconditional surrender and warned of “prompt and utter destruction” if they refused.

President Truman and his commanders figured that dropping the atomic bombs would force Japan to surrender fast. They hoped it would end the war without the massive losses an invasion would bring.

How did the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki influence Japan’s decision to surrender?

Japan announced its surrender six days after the Nagasaki bombing, on August 15, 1945. The atomic bombs made it clear that America had a terrifying new weapon—and was willing to use it again.

Emperor Hirohito mentioned the enemy’s use of “a new and most cruel bomb” in his surrender speech. He said that continuing the war would mean the total destruction of Japan.

The Soviet Union entering the war on August 8 also played a big role. Soviet forces invaded Manchuria, wiping out Japan’s last hope of negotiating peace through Moscow.

The combination of atomic bombings and the Soviet invasion left Japan’s leaders feeling like resistance was pointless. The government surrendered on September 2, 1945, bringing World War II to a close.

What were the immediate and long-term effects of the atomic bombings on the populations of Hiroshima and Nagasaki?

By the end of 1945, the death toll hit 90,000 to 166,000 in Hiroshima and 60,000 to 80,000 in Nagasaki. About half died on the first day.

The bombs wiped out huge sections of both cities in seconds. In Hiroshima, the blast leveled five square miles and destroyed over 60 percent of the buildings.

Radiation sickness struck thousands in the months that followed. Many kept dying from burns, radiation, and illnesses made worse by malnutrition.

Long-term, survivors faced higher rates of cancer, especially leukemia. Kids exposed to radiation developed more thyroid cancer and other health problems years later.

Survivors—hibakusha—carried deep psychological scars. Many of them also faced discrimination and ongoing health struggles for the rest of their lives.

What considerations were made when selecting Hiroshima and Nagasaki as targets for the atomic bombings?

Military planners picked big cities with key military facilities. Hiroshima, Kokura, Niigata, and Nagasaki made the shortlist on July 25, 1945.

Hiroshima had a major garrison—about 24,000 troops—and acted as a command center with important war industries.

Nagasaki ended up as the backup target when clouds blocked Kokura on August 9. The city was known for shipbuilding and steel production.

These cities hadn’t been hit hard by earlier bombing raids. That way, officials could see exactly what the atomic bomb could do.

They wanted cities big enough to really show the weapon’s power. The idea was to send a clear message about the consequences of continued resistance.

What were the names of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and what were their differences?

The bomb dropped on Hiroshima was called “Little Boy.” It was a uranium-based weapon that used a gun-type fission design to set off the explosion.

“Fat Man” was the plutonium bomb used on Nagasaki three days later. This one used an implosion design that compressed plutonium to trigger the blast.

Little Boy packed a punch equal to about 15,000 tons of TNT. Its design was simpler, but it needed more fissile material than the plutonium bomb.

Fat Man blew with the force of roughly 21,000 tons of TNT. The implosion design was trickier but more efficient and used less fissile material.

Both bombs were dropped by specially modified B-29 Superfortress planes. The 509th Composite Group trained just for these missions.

What were the global implications and historical significance of the atomic bombings for post-war international relations?

The atomic bombings kicked off the nuclear age and flipped international relations on their head. Suddenly, everyone realized a single bomb could wipe out a whole city—hard to ignore, right?

After World War II, the United States stood alone as the only country with nuclear weapons. That fact handed America a pretty big edge in early post-war talks and power plays.

These bombings seriously ramped up tensions between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. The Americans’ nuclear monopoly fueled the brewing Cold War rivalry.

It didn’t take long for other countries to chase after their own nuclear arsenals. The Soviets pulled off their first atomic bomb test in 1949, and the arms race was on.

Nuclear deterrence quickly became a core idea in global politics. Leaders started planning around the threat of mutual destruction—grim, but it changed the game.

Right after the war, countries kicked off efforts to control nuclear weapons. The bombings made it painfully obvious that treaties and agreements were necessary to stop nuclear weapons from spreading.

References and literature

Luftkrieg (Piekalkiewicz)

Der 2. Weltkrieg (C. Bertelsmann Verlag)

Zweiter Weltkrieg in Bildern (Mathias Färber)

A World at Arms – A Global History of World War II (Gerhard L. Weinberg)

Den Krieg denken – Die Entwicklung der Strategie seit der Antike (Beatrice Heuser)