Operation ‘Seelöwe’ (Sea Lion): German Plan for the Invasion of Britain in WW2.

Table of Contents

After conquering France and much of Western Europe by the summer of 1940, Nazi Germany set its sights on Britain. Operation Seelöwe (Sea Lion) was the German military’s code name for their planned invasion of the United Kingdom, scheduled for September 1940.

This was Hitler’s big swing at dominating Western Europe and knocking Britain out as a base for military operations against the Axis powers. The plan was bold, maybe even reckless, but Germany had momentum.

The invasion meant smashing through challenges that had protected Britain for centuries. German forces needed to win the skies and seas over the English Channel, crush the Royal Air Force, and somehow keep the Royal Navy at bay.

Those requirements turned out to be a lot tougher than Germany’s earlier victories on the continent. The operation never got off the ground, but the planning and buildup shaped the war’s direction.

Historical Context and Strategic Background

By summer 1940, Nazi Germany had racked up a string of stunning victories across Western Europe. Britain stood alone, looking pretty vulnerable after Dunkirk.

The Dunkirk evacuation saved a lot of British troops, but Hitler figured invasion might finish the job. His confidence was sky-high.

Position of Nazi Germany in 1940

By mid-1940, Nazi Germany was at its military peak. The Wehrmacht had steamrolled Poland, Denmark, and Norway in quick succession.

Operation Weserübung in April 1940 knocked out Norway and Denmark in weeks, giving Germany access to key North Sea ports and airfields.

The Western Europe campaign kicked off on May 10, 1940. In just six weeks, German forces brought down the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and France.

By June, the Axis dominated continental Europe. Britain was left as Germany’s last big opponent in the West.

The German military machine seemed unstoppable. With superior tactics and equipment, they’d outclassed their enemies so far.

Aftermath of Dunkirk and Western Europe Campaign

The Dunkirk evacuation ran from May 26 to June 4, 1940. British and Allied troops scrambled across the Channel while German forces pressed hard.

Some 338,000 British and French soldiers made it out, but they left behind almost all their heavy gear, tanks, and artillery.

Britain’s army survived, but it was battered and needed months to recover. The losses in France were a tough blow.

France surrendered on June 22, 1940. Britain suddenly found itself isolated, with no major allies left in Europe.

Hitler believed Britain would come to the table for peace after France fell. He saw their situation as pretty much hopeless without friends on the continent.

Hitler’s Objectives for the Invasion

Adolf Hitler saw the invasion as the last step to secure Western Europe. As long as Britain held out, his plans for expansion to the east were at risk.

The main goal was to neutralize Britain as a military threat. Hitler wanted to make sure Britain couldn’t be a launchpad for Allied attacks against Germany.

Taking Britain would secure Germany’s western flank before moving on to Operation Barbarossa against the Soviet Union. For Hitler, this was non-negotiable.

The plan also included grabbing British naval assets and ports. That would boost German naval strength and remove the Royal Navy from the equation.

Hitler eyed Britain’s industry and resources, too. A successful invasion would bring big economic advantages for Germany’s war effort.

German Invasion Plans and Objectives

Germany started drafting detailed invasion plans, picking landing sites along the Channel and setting tight timetables for the assault. The planning was intense, if a bit rushed.

Development of Operation Seelöwe

German military leaders started thinking about invading Britain as early as winter 1939-40. Admiral Erich Raeder pushed for plans in case Britain kept fighting after France fell.

Early planning zeroed in on the huge logistics of crossing the Channel. Planners studied the British coast, looking for weak spots.

The operation needed the army, navy, and air force to work together. The Kriegsmarine would handle the crossing, the Luftwaffe had to win the skies, and the Wehrmacht would storm the beaches.

German intelligence gathered piles of info on British towns and possible landing spots. They took tons of photos of the southern English coastline.

Führer Directive No. 16 and OKW Involvement

On July 16, 1940, Hitler gave the green light with Führer Directive No. 16. That made the invasion official and gave it the codename “Unternehmen Seelöwe.”

The Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW) took charge of planning, working closely with the Oberkommando des Heeres (OKH) on strategy.

Hitler spelled out the main goals:

- Knock Britain out as a base for war

- Occupy the country if needed

- Put the British Isles under German control

But OKW hit a wall right away with naval transport. Germany just didn’t have enough landing craft for such a massive Channel crossing.

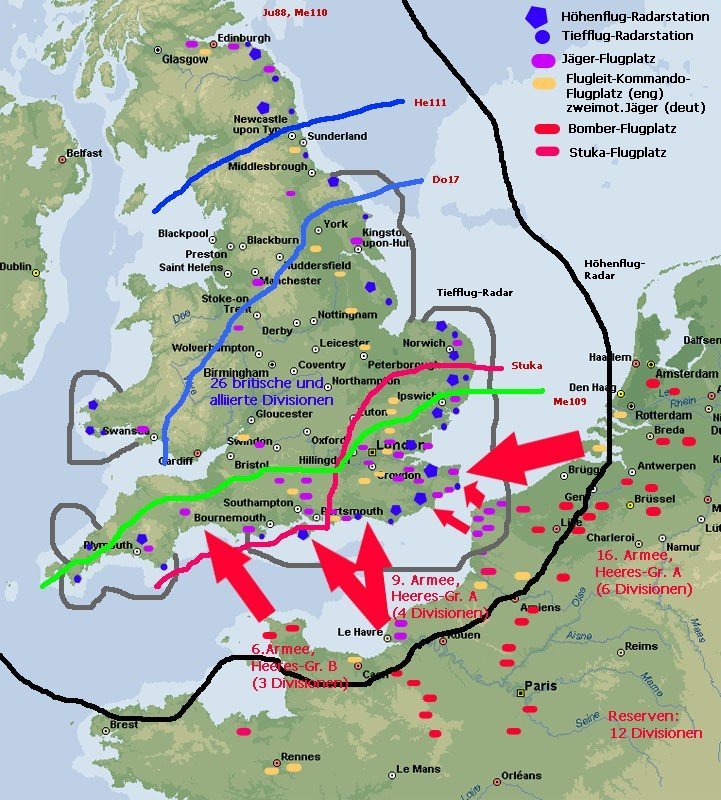

Selection of Landing Sites and Timetables

Planners picked southeast England as the main target. Kent was closest to Northern France, making it the obvious choice.

Top landing sites were:

- Folkestone – big port

- Eastbourne – wide beaches

- Ramsgate – strategic location

- Areas near the Isle of Wight

The invasion was penciled in for September 1940. The plan was to land, grab beachheads, then push toward London within days.

They split the attack into waves. The first would secure the coast, and the next would drive inland to seize key cities and transport lines.

Everything hinged on good weather and tides. German meteorologists studied the Channel, hoping for the right window, but the British weather is famously unpredictable.

German Military Preparations

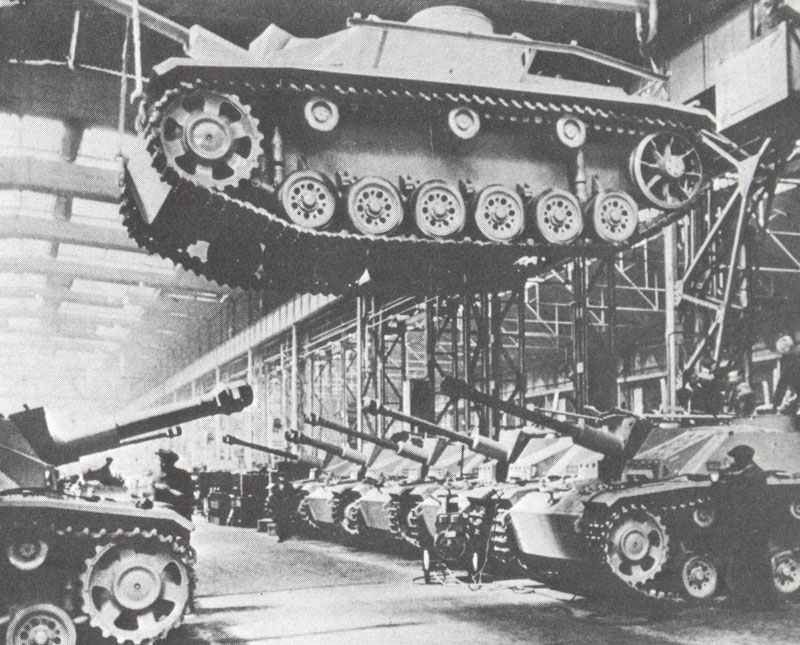

The Wehrmacht started prepping for Operation Sea Lion across all branches, but every part of the plan had serious hurdles. The German Army tried to master amphibious tactics, while the Kriegsmarine scrambled to collect and modify thousands of river barges for the crossing.

Composition and Readiness of the Wehrmacht

The German Army aimed to send about 160,000 infantry in the first wave. General Franz Halder ran the show for ground operations.

The Wehrmacht had crushed Poland and France, but this kind of amphibious assault was a whole new ballgame. No one really knew how it would go.

The invasion force included several army groups. The 9th and 16th Armies were set to lead, with regular infantry and some motorized units in the mix.

Key Wehrmacht Components:

- First Wave: 13 infantry divisions

- Second Wave: More motorized and armored units

- Reserve Forces: Panzer divisions for breakthroughs

The army had to invent new tactics for beach landings. Soldiers trained along the French coast, but nobody had experience with an operation this size over water.

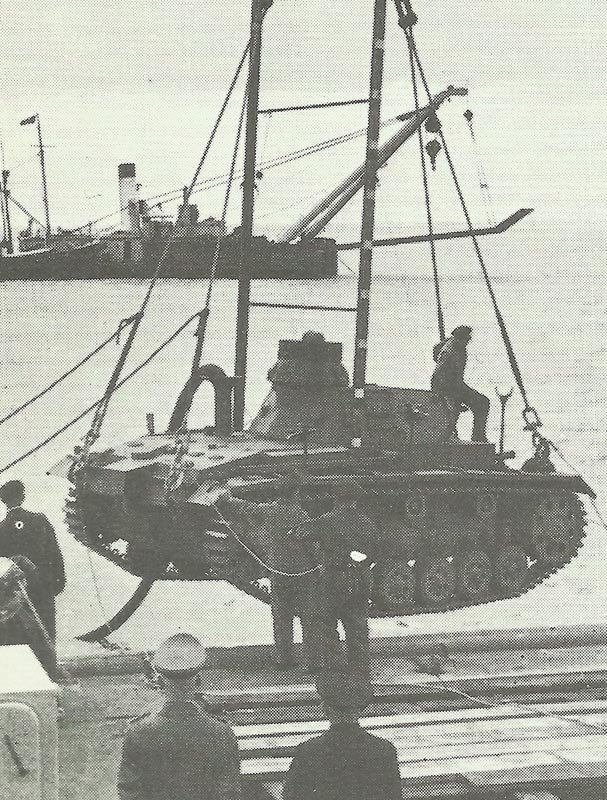

Amphibious Assault Forces and River Barges

The Kriegsmarine, led by Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, faced a daunting job: getting the invasion force across the Channel. The navy rounded up over 2,400 river barges from all over Europe.

Engineers worked overtime to make these barges seaworthy, adding reinforced hulls and ramps for landings. The barges could haul tanks and supplies, but they were still pretty fragile in rough seas.

Transport Fleet Composition:

- River Barges: 2,400+ vessels

- Motor Boats: 1,200+ craft

- Steamers: 200+ ships

- Tugs: 300+ vessels

The plan was to tow the barges with tugs and steamers—a slow, easy target for the Royal Navy. U-boats were supposed to help, but Admiral Karl Dönitz didn’t have many to spare.

The navy also built special landing craft, plus modified fishing boats for the first wave. It was a patchwork solution, honestly.

Role of Airborne Troops and Special Units

German airborne troops were crucial to the plan. The Luftwaffe’s paratroopers would jump in to grab airfields and bridges before the main landings.

The 7th Air Division was the core of this force. Paratroopers would drop near Dover and other key spots, aiming to take ports and communication centers fast.

Special engineering units got ready to build temporary harbors. German pioneers designed portable piers and floating bridges to keep supplies moving once the beachheads were set.

Airborne Operations Planned:

- Seize airfields near Canterbury and Dover

- Take control of road and rail junctions

- Cut British communication lines

The Luftwaffe also trained glider crews to deliver heavy gear. These quiet planes could bring artillery and supplies to the paratroopers behind enemy lines.

Key Prerequisites and Challenges

Operation Sea Lion forced Germany to tackle three huge problems before even thinking about an invasion. Hitler insisted on air superiority over Britain, full naval control of the Channel, and a way to move thousands of troops and tons of gear across some of the most dangerous waters in the world.

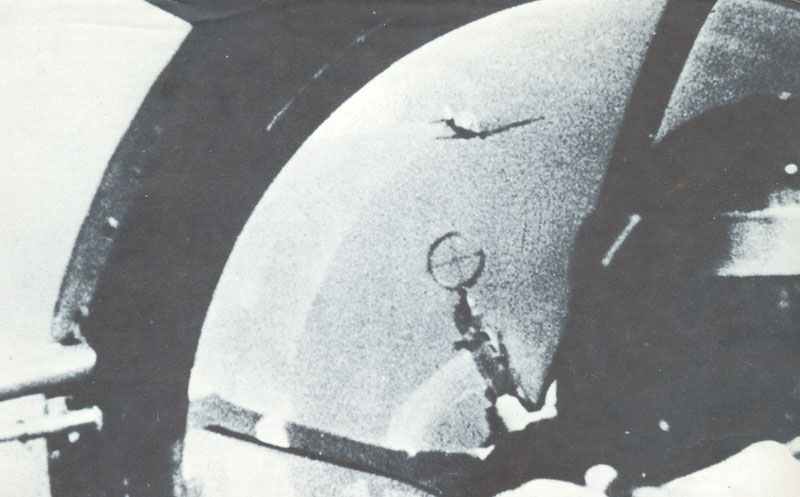

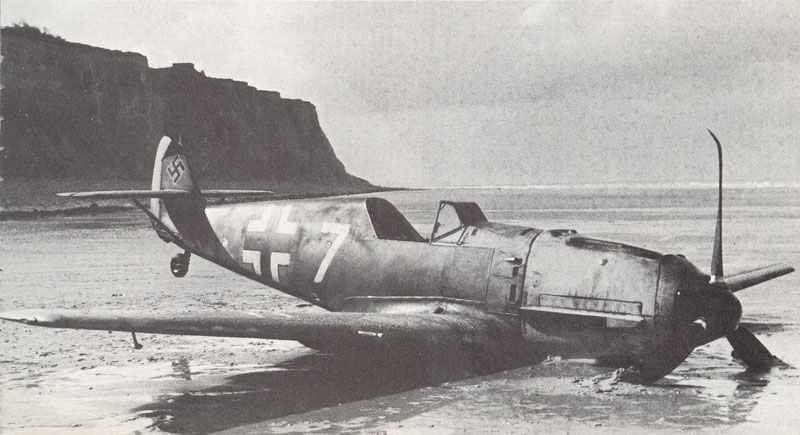

Achieving Air Superiority in the Battle of Britain

The Luftwaffe had to break the Royal Air Force before any invasion could happen. Hitler’s Directive No. 16 demanded the RAF be “beaten down in its morale and in fact”—basically, out of the fight.

German planners figured they’d need about two to four weeks to pull off air superiority. Their plan? Smash RAF factories and supply lines first.

The Battle of Britain quickly showed how naive that was. British airfields bounced back from bombings with impressive speed, and the RAF’s radar network kept them in the game.

German losses kept piling up. By September 1940, the Luftwaffe hadn’t knocked out British air defenses, and Hitler shelved Sea Lion on September 17, 1940.

Confronting the Royal Navy and British Mines

The British Royal Navy was a nightmare for German planners. After heavy losses in Norway, Germany only had one heavy cruiser, two light cruisers, and four destroyers left for the job.

Royal Navy home squadrons outnumbered the Germans by a mile. Hitler wanted British ships “damaged or destroyed by air and torpedo attacks” to keep them away from the crossing.

British mines made things even worse. The Germans had to sweep the Channel clear at crossing points and plant their own mines in the Strait of Dover, all while under fire.

The Channel crossing itself was a gamble. Germans needed to control the coast and have big guns ready. Weather in the North Sea could turn ugly fast, and those invasion barges weren’t built for rough seas.

Logistical Hurdles and Channel Crossing Risks

Shuffling huge numbers of troops across the Channel meant a logistical headache. At first, the army wanted landings from Kent to Dorset, then narrowed it to four sites in East Sussex and western Kent.

The German navy said it needed at least a year to get enough ships together. They had to round up river barges and tinker with transport vessels, most of which weren’t exactly seaworthy.

Bridges and ports had to go up in a hurry after landing. German forces had never done anything like this before—not like the Japanese, who had pulled off big amphibious landings in 1938.

Weather was always a wild card. September in the Channel could get nasty with little warning. The channel crossing would take at least ten days for the first wave, leaving troops exposed to British attacks the whole time.

British Defenses and Countermeasures

Britain called up 1.5 million Home Guard volunteers and scrambled to rebuild its military after losing most of its gear at Dunkirk. They built a web of fortifications across southern England, and radar stations gave early warning of German raids.

Rearmament After Dunkirk and Home Guard Mobilization

The British Army left most of its heavy stuff behind at Dunkirk in May 1940. Over 338,000 men made it back, but France kept their tanks and artillery.

By June, Britain had 22 infantry divisions, but they were understrength and short on artillery. They had about 600 medium guns and 280 howitzers, with more coming from the U.S.

Tank strength grew rapidly:

- June 10: 366 tanks total

- September 15: 684 tanks total

- Infantry tanks increased from 74 to 224

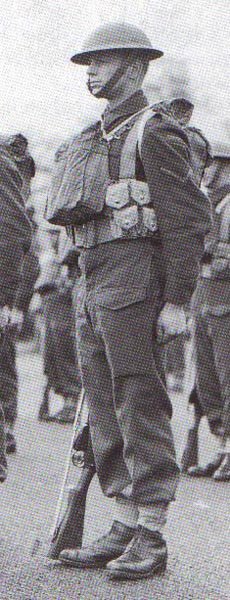

The Home Guard started on May 14, 1940, as Local Defence Volunteers. Nearly 1.5 million men signed up by the end of June—way more than anyone expected.

Early Home Guard units made do with private guns, homemade spears, and Molotov cocktails. By July, they got uniforms and half a million American rifles.

The Home Guard also picked up sticky bombs, glass grenades, and makeshift armoured cars. They used whatever they could—bikes, motorcycles, even personal cars—to get around.

Defensive Structures and Early Warning Systems

Britain built a maze of field defenses across the south, turning the countryside into a fortress. Concrete pillboxes, anti-tank blocks, and gun positions guarded the coast.

The Chain Home radar network started going up before the war, with three stations ready by 1937. These radars gave Britain a heads-up on incoming German planes during the Battle of Britain.

Coastal defenses focused on Kent and neighboring counties, where a German landing seemed most likely. Beaches got obstacles, mines, and more guns.

Military planners had orders to blow up airfields and radar gear if the Germans got too close. They’d try to move portable radar, but if not, they’d destroy it.

The RAF came up with Operation Banquet as a last resort, planning to turn every available plane—including 350 Tiger Moth trainers—into bombers armed with 20-pound bombs.

Role of the 1st Canadian Infantry Division

The 1st Canadian Infantry Division landed in Britain as part of the mobile reserve. They joined VII Corps, which was stationed south of London at Headley Court in Surrey.

VII Corps had the 1st Armoured Division, 1st Canadian Division, and 1st Army Tank Brigade. This group was the main counterattack force if the Germans made it ashore.

The Canadians brought solid soldiers and modern gear, shoring up Britain’s defenses. Their presence let British commanders keep a strong reserve behind the front lines.

Canadian troops trained hard for counterattacks against possible German beachheads. They practiced moving quickly to any threatened spot along the southern coast.

Australia also chipped in, sending two infantry brigades from the 6th Division to Britain between June 1940 and January 1941.

Analysis and Outcome of Operation Seelöwe

Operation Seelöwe got the axe on September 17, 1940, after Germany failed to win the air war over Britain. With that, German attention turned east toward the Soviet Union, and the detailed invasion plans ended up as fascinating material for historians and wargamers.

German Decision to Cancel the Invasion

Hitler shelved Operation Seelöwe for good on September 17, 1940, once the Luftwaffe couldn’t beat the RAF. German air crews took a pounding from Spitfires and Hurricanes all summer.

The Kriegsmarine, already battered after Norway, just couldn’t protect the invasion barges. The Royal Navy still ruled the Channel.

Key reasons for the cancellation:

- Air superiority: The Luftwaffe couldn’t take out British air defenses

- Naval control: The Royal Navy owned the Channel

- Logistics: River barges weren’t up to the job

- Weather: Autumn storms made crossings even riskier

By October 1940, the invasion fleet broke up. German focus shifted to planning the invasion of the Soviet Union.

Influence on Operation Barbarossa and the War

Canceling Seelöwe led straight to Hitler launching Operation Barbarossa in June 1941. Germany suddenly faced a two-front war with Britain still fighting back.

Troops and supplies meant for Britain went east instead. The delay gave Britain time to beef up defenses and build alliances.

- Britain stayed an Allied stronghold

- German forces got split between different fronts

- The Normandy landings in 1944 launched from British soil

- Soviet-British cooperation grew with Germany distracted

Britain kept getting U.S. aid through Lend-Lease. British intelligence expanded operations all over occupied Europe.

Legacy, Documents, and Wargaming Scenarios

German planners left behind a mountain of paperwork for the invasion, including the Sonderfahndungsliste G.B. (“Black Book”) with 2,820 names of Brits marked for arrest.

They had plans for a Reichskommissar für Großbritannien—candidates included Joachim von Ribbentrop and Ernst Wilhelm Bohle. Blenheim Palace was supposed to be HQ.

Oswald Mosley, head of the British Union of Fascists, was pegged as a possible puppet leader.

Modern wargamers love Seelöwe scenarios. SPI published Operation Sea Lion as a board game in the 1970s, and most playthroughs end with the Royal Navy stomping the invasion.

The detailed German docs give historians a rare look at Nazi plans for occupying Britain. There’s a trove of maps, photos, and admin guidelines showing just how methodical the Germans tried to be.

Frequently Asked Questions

Operation Sea Lion was a logistical and strategic beast, and the obstacles proved too much. The German plan needed massive military resources and ran into stubborn British resistance during the Battle of Britain.

What strategic objectives did Germany aim to achieve with Operation Sea Lion?

Germany wanted Operation Sea Lion to knock Britain out as a base against the Axis. Hitler aimed to end any chance of Britain continuing the fight from home turf.

The goal was to force Britain into a peace deal, take control of the English Channel and the coast, and stop Britain from launching future attacks on German-occupied Europe. Ending British support for resistance movements was another part of the plan.

How did the Battle of Britain impact the execution of Operation Sea Lion?

The Battle of Britain basically sealed Sea Lion’s fate. Hitler needed air superiority over the Channel, or there was no invasion.

The Luftwaffe couldn’t beat the RAF in the summer of 1940. German air losses kept climbing, and they never gained control of the skies.

So, Hitler put Sea Lion on ice for good on September 17, 1940. The air force just couldn’t deliver the knockout blow needed for invasion.

What were the primary reasons for the ultimate cancellation of Operation Sea Lion?

Germany never managed to meet the four conditions Hitler demanded for invasion. The RAF, honestly, just wouldn’t quit—they held strong all through the Battle of Britain.

The German Navy simply didn’t have enough ships to ferry invasion forces safely. They’d already lost a bunch of vessels during the Norway campaign earlier in 1940.

Admiral Raeder and Hermann Göring, among other military leaders, didn’t really buy into the invasion plan. They doubted it could work with Britain’s navy and air force so dominant.

And then there was the weather—always unpredictable in the Channel. September 1940 just didn’t cooperate.

Which military resources were allocated by Nazi Germany for the planned invasion?

Germany gathered up a huge fleet of river barges and transport ships along the Channel coast. They even took civilian boats and reworked them to haul troops and gear across the water.

The Army trained up special units for amphibious landings. They also started tinkering with new weapons and gear for hitting the beaches.

The Luftwaffe geared up for heavy bombing runs to back the invasion. Meanwhile, the Navy hustled to clear sea mines and set up artillery along the French coast.

What was the planned extent of the invasion and occupation by German forces?

The first German plans aimed for landings from Kent all the way to Dorset, including the Isle of Wight and parts of Devon. They pictured a wide-front assault right across southern England.

Later on, they narrowed it down to four main landing sites in East Sussex and western Kent. Focusing like that was supposed to pack more punch in a smaller area.

The idea was to put 100,000 infantry on the beaches in the first wave. Planners hoped they could grab solid beachheads and then push inland toward London.

How did British defenses and military preparations counteract Operation Sea Lion?

The Royal Air Force kept its fighter squadrons in the air during the Battle of Britain. British pilots managed to fend off German bombing raids that targeted airfields and radar stations.

The Royal Navy held strong naval forces close to home, just in case Germany tried to invade. Their warships waited, ready to strike at German transport vessels if they dared to cross the Channel.

Britain put serious effort into coastal defenses along likely landing spots. The military also set up inland defenses and drew up evacuation plans for civilians living in high-risk areas.

British intelligence kept a close watch on German invasion plans across the French coast. This intel let military leaders react quickly and adjust their defenses as needed.

References and literature

Luftkrieg (Piekalkiewicz)

Chronology of World War II (Christopher Argyle)

Der Grosse Atlas zum II. Weltkrieg (Peter Young)

Das Deutsche Reich und der Zweite Weltkrieg (10 Bände, Zentrum für Militärgeschichte)

Der 2. Weltkrieg (C. Bertelsmann Verlag)

Zweiter Weltkrieg in Bildern (Mathias Färber)

A World at Arms – A Global History of World War II (Gerhard L. Weinberg)