The Japanese Army in the Pacific War 1943 to 1945.

Distribution of the Japanese armed forces in August 1943 and 1945, the armoured divisions, independent units, amphibious brigades and the land forces of the navy.

Japanese army on the defensive 1943-45

Table of Contents

In the years 1943-1945, the Japanese army found itself increasingly on the defensive as the tide of the Second World War turned against Japan.

Overview

Shift in momentum:

– After initial successes in 1941-42, Japan began to lose ground to Allied counterattacks.

– The Battle of Midway (June 1942) marked a turning point in the Pacific War.

Island-hopping strategy:

– The Allies pursued an ‘island-hopping’ strategy, bypassing the heavily fortified Japanese positions.

– This approach put increasing pressure on Japanese defence capabilities.

Defensive fortifications:

– The Japanese forces built extensive defence rings on the islands in the Pacific.

– These included bunkers, tunnels and artillery positions that could withstand bombardment.

Kamikaze tactics:

– As the situation became increasingly desperate, Japan introduced kamikaze suicide attacks in October 1944.

– This tactic was intended to inflict maximum damage on the Allied naval forces.

Important defence battles:

– Battle of Guadalcanal (1942-43): First major Allied offensive in the Pacific.

– Battle of Tarawa (1943): Shows how difficult it is to attack fortified Japanese positions.

– Battle of Peleliu (1944): Demonstration of Japanese tenacity in defence.

– Battle of Iwo Jima (1945): Shows the sophisticated Japanese underground defence.

– Battle of Okinawa (1945): The largest amphibious offensive in the Pacific War.

Resource scarcity:

– Japan found it increasingly difficult to supply and reinforce its widely dispersed garrisons.

– Shortages of fuel, ammunition and food impaired defence capabilities.

Defence doctrine:

– Japan’s strategy was to inflict as many casualties as possible on the invading forces.

– The aim was to keep the costs of the invasion so high that the Allies would seek a negotiated peace.

Bushido code and doctrine of refusal to surrender:

– Japanese soldiers were indoctrinated to fight to the death rather than surrender.

– This led to fierce resistance and high casualty rates on both sides.

Defence of the home islands:

– As the Allied forces approached Japan proper, extensive defences were built on the home islands.

– These preparations included civilian militias and suicide weapons such as explosive speedboats.

Technological disadvantage:

– Japan increasingly lagged behind the Allies in terms of military technology and production capacity.

– This disadvantage hampered the ability to mount an effective defence against Allied advances.

Limited naval and air support:

– The decimation of the Japanese navy and air force meant that ground forces had little support.

– This made defence operations increasingly difficult, especially on isolated islands.

Psychological factors:

– Despite the deteriorating conditions, many Japanese soldiers maintained a strong fighting spirit.

– Propaganda and cultural factors contributed to their continued resistance even in hopeless situations.

The Japanese army’s defensive posture in 1943-45 was characterised by determination and ingenuity in the face of overwhelming inferiority. However, a shortage of resources, strategic miscalculations and the technological superiority of the Allies ultimately led to Japan’s defeat in August 1945.

Organisation of the Japanese Army 1943-45

The Japanese Army on the defensive reached a maximum strength of 5 million men in 140 divisions during World War II, with numerous independent smaller units.

The summer of 1942 marked the high-water mark of the Japanese advance, and as America’s great industrial and military might come to bear, the Japanese Army was forced onto the defensive. In the Pacific, US troops waged a fierce campaign of ‘island hopping’ and in Burma the British finally succeeded in gaining the upper hand over the widely dispersed Japanese army.

In action, the Japanese land forces were divided into army groups, section or divisional armies, armies and divisions. There were also ‘units with special missions’, which were not subordinate to a specific army or division.

Army groups comprised an entire theatre of war, such as the Japanese Home Defence Army, the Kwangtung Army or the Southern Army Group. A section army, for example in Burma, was roughly equivalent to a German field army.

The Japanese army was much smaller than its German counterpart and was roughly equivalent to a strong corps. On the other hand, there were no army corps in the Japanese armed forces.

Distribution of the Japanese armed forces outside Japan in August 1943:

Army Group | Armies | Divisions |

|---|---|---|

Kwantung Army Group (Manchuria) | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 20 Army | total 15 Infantry divisions |

China Expeditionary Force | 1, 11, 12, 13, 23 and Mongolian Garrison Army | total 1 armoured and 25 Infantery divisions. |

8th Section Army | 17th Army (Solomon Islands), 18th Army (Western New Guinea) | total 6 infantry divisions |

Southern Army Group | 19th Army (Eastern New Guinea, Celebes, Timor, Amboina) | total 2 infantry divisions |

16th Army (Java) | total 2 infantry divisions |

|

25. Armee (Malaya und Sumatra) | total 1 Infantry division |

|

Burma Section Army with the 15th Army | total 6 infantry divisions |

|

Siam Garrison Army | total 1 infantry division |

|

Borneo Garrison Army | no division units |

|

Indochina | 21st Infantry Division |

|

Subordinate to the Imperial Headquarters | Korea Army | total 2 infantry divisions |

Northern Army (Kuril Islands, Sakhalin, Hokkaido) | total 1 Infantery division |

|

Formosa Army | no division units |

|

14th Army (Philippines) | total 2 infantry divisions |

Even though the war was clearly lost for Japan by 1944, the Japanese army continued to fight as resolutely as ever on the defensive, and did so until the day of surrender on 2 September 1945, when orders were given to lay down arms.

In total, Japan had seven armoured divisions (four of which never left Japan) and 162 infantry divisions (55 of which never left Japan and 19 others never saw combat in their area of operations) during the Second World War.

Japan’s armed forces suffered 1.7 million casualties during the Second World War.

Distribution of Japanese forces outside Japan in August 1945:

Army Group | Section Armies | Armies | Divisions |

|---|---|---|---|

Kwantung Army Group (Manchuria) | 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th, 20th Army | Total 1 armoured and 10 infantry dvisions |

|

China Expeditionary Force | 1st, 12th, 13th, 23rd, 6th Area Army (11th, 23rd Army) and Mongolian Garrison Army | Total 1 armoured and 25 infantry divisions |

|

Subordinate to the Imperial Headquarters | 5th Section Army | 27th Army (Kuril Islands, Sakhalin, Hokkaido) | Total 4 infantry divisions |

Southern Army Group | 14th Section Army | 35th Army (Philippines) | Total 2 armoured and 11 infantry divisions |

2nd Section Army | 2nd Army, isolated 19th Army (in eastern New Guinea, Clebes. Amboina, Timor) | Total 6 infantry divisions |

|

7th Section Army | 16th and 25th Army (Sumatra), 29th Army (Malaya), 37th Army (Sumatra). Army (Borneo) | Total 10 infantry divisions |

|

(subordinate to the Army Group) | 18th Army (New Guinea) | Total 3 infantry divisions |

|

Burma Section Army | 15th, 28th, 33rd Army | Total 10 infantry divisions |

|

(subordinate to the Army Group) | 38th Army (Indochina) | Total 1 infantry division |

|

(subordinate to the Army Group) | 39th Armee (Siam) | no divisional units |

|

Subordinate to the Imperial Headquarters | Korea Army | Total 1 Infantery division |

|

Formosa Army | Total 3 infantry divisions |

||

31st Army (Central Pacific; isolated) | Total 5 infantry divisions |

||

32nd Army (Ryukyu Islands) | Total 4 infantry divisions |

||

8th Section Army | 17th Army (isolated) | Total 3 infantry divisions |

Japanese armoured divisions

The armoured regiment had a headquarters, three or four armoured companies and a regimental ammunition train. The strength of the regiment consisted of around 90 light and medium tanks and 800-850 men.

In addition, there was an artillery regiment with eight 105-mm guns and four 155-mm howitzers, an anti-tank unit with 18 x 48-mm anti-tank guns and an anti-aircraft unit with four 75-mm and 16 x 20-mm anti-aircraft guns.

There was also support from engineer, transport and medical units.

The entire division consisted of about 10,500 men and 1,850 vehicles. The Japanese armoured divisions were able to achieve some successes against poorly equipped Chinese forces, but were in no way equal to the armoured units of the other major powers.

Independent units

The Japanese army also had a large number of independent units, and it was easy for commanders to organise special forces for specific missions. Instead of adding heavy weapons such as anti-tank guns and artillery to all of these units, these weapons were also organised into independent units so that they could be added to other units as needed.

This trend reinforced the fragmentation tendencies of the Japanese armed forces. In the early days of the Pacific War, such combined battle groups successfully led the Japanese advance through Malaya, the Dutch East Indies and into the Solomon Islands.

However, the heavy losses suffered by the Japanese from the second half of 1942 onwards were often due to the careless deployment of small battle groups that were thrown together and had inadequate joint coordination and unit training.

For example, one of these independent units, the “6th Independent Anti-Aircraft Battalion”, was transported from cold Manchuria to tropical Guadalcanal in just 23 days to reinforce the ragtag task force that was to hastily recapture the island.

One of these typical roles was the attempt by Japanese special forces in Burma to destroy British artillery through commando-style operations. The strength of these forces varied with the size of their targets.

A typical example was:

Headquarters Group (officer, NCO and orderly);

Destroyer and Assault Group (15 men);

Support Group (12 men);

Reserve Section (12 men).

In addition, there were small groups organised for raids into enemy territory. They were to destroy bridges and communication lines, attack bunkers and fortified positions, demolition squads and anti-tank units. Finally, there were also kamikaze commandos that fought to the last man in defence of a crucial point.

Amphibious brigades

Within the more traditional army structure, special provisions were made for amphibious operations. After 1941, amphibious brigades were formed from three battalions with a total strength of 3,200 men.

Each battalion was 1,035 strong and had three rifle companies of 195 men each, organised into three platoons of four sections each and a grenade launcher platoon.

The 1st Amphibious Brigade had supporting artillery, engineer, machine-gun, intelligence and armoured units, which were subordinate to the brigade headquarters. This brought their total strength to around 4,000 men.

During the advance through Malaya, each Japanese division was equipped with 50 small motorboats and 100 collapsible launches for the attack on Singapore. The troops carried all this material on their own shoulders through the jungle. A first wave of 4,000 men with 440 guns – each equipped with 20 rounds of ammunition – was ferried in this way.

Land forces of the navy

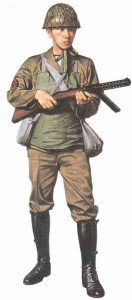

Sailor 1st class of the Japanese Navy equipped for land combat, 1939.

Under the “ad hoc” tradition of the Japanese army, when amphibious operations were imminent, Marine landing parties were improvised for individual missions.

Each naval recruit was trained in both land and sea warfare. If a recruit was suitable for land warfare and showed special skills, such as mastery of a machine gun or the ability to drive, this was noted in his file.

The fleet commander ordered several ships to provide troops for amphibious operations and attack groups were organised from their crews. It goes without saying that the military training of these sailors was scarce and their losses high.

In the 1920s, the Japanese navy began experimenting with special naval landing parties to avoid these heavy losses of well-trained naval personnel. These were permanent units that were first deployed in China in 1932.

the base forces, the ground forces, the pioneers and the engineering and construction units. However, these formations never reached the class of the American Marines.

The Navy’s special landing forces usually remained in the areas they had previously conquered as garrisons. When there was no serious resistance, their efficiency was high, but their tactical skills were mediocre against a determined enemy.

Initially they were organised in battalions of about 2,000 men from four companies. The first three companies were divided into six rifle platoons and a heavy machine-gun platoon. The last company, the fourth, consisted of three rifle platoons and a heavy weapons platoon equipped with four 76.2-mm naval guns and two 75-mm regimental guns as well as two 70-mm battalion guns. Depending on the circumstances, they could be reinforced with armoured or armoured car units.

At the outbreak of war in the Pacific, they were used to capture small islands such as Wake and served as spearheads for the army against Java and Rabaul. In these operations, they could be used as mobile combat troops.

They were usually deployed with two rifle companies (each with its own machine-gun platoon) and one or two companies of heavy weapons with a strength of 1,200 to 1,500 men. They could also receive additional specialised support troops, as well as sappers, additional guns and intelligence troops.

When Japan lost the initiative in the Pacific Ocean, these forces had to prepare for a defensive war, especially when the army refused to defend some of the islands, claiming that they were the responsibility of the navy.

Consequently, these formations were adapted to the changed circumstances. A typical example of this was the Yokosaka 7th Marine Special Landing Force. When first deployed at the beginning of the Pacific War, this formation had no infantry for defensive purposes and no heavy defensive weapons.

By 1943, the platoon rather than the company became the basic tactical unit and the proportion of artillery was significantly increased.

From 1943, a special landing force for defensive tasks usually consisted of 1,800 officers and men and was equipped with

1,500 rifles;

24 light and 12 heavy machine guns;

two 40-mm anti-aircraft guns and ten 13-mm anti-aircraft machine guns;

90 grenade launchers;

four mortars;

four 75-mm anti-aircraft guns;

two 37-mm anti-tank guns;

16 x 80-mm guns

and 8 x 120-mm guns.

References and literature

The Armed Forces of World War II (Andrew Mollo)

World War II – A Statistical Survey (John Ellis)

Japanese Army of World War II (Philip Warner)