The Italian armed forces after September 1943 until 1945: Mussolini’s ‘Italian Socialist Republic’ in the north and the ‘Co-Belligerent’ troops of the Kingdom of Italy fighting on the Allied side in the south.

The Italian armed forces 1943 to 1945

Table of Contents

After Mussolini’s deposition and the subsequent Italian capitulation, two new armed forces emerged in Italy: the fascist troops of Mussolini’s ‘Italian Socialist Republic’ (RSI), which were deployed against partisans and Allied troops, as well as against the ‘Co-Belligerent’ units of the Kingdom of Italy from the south, which was fighting on the Allied side. In addition to the battles between German and Allied troops, this often led to civil war-like clashes between the two opposing Italian camps.

Army of the Italian Socialist Republic

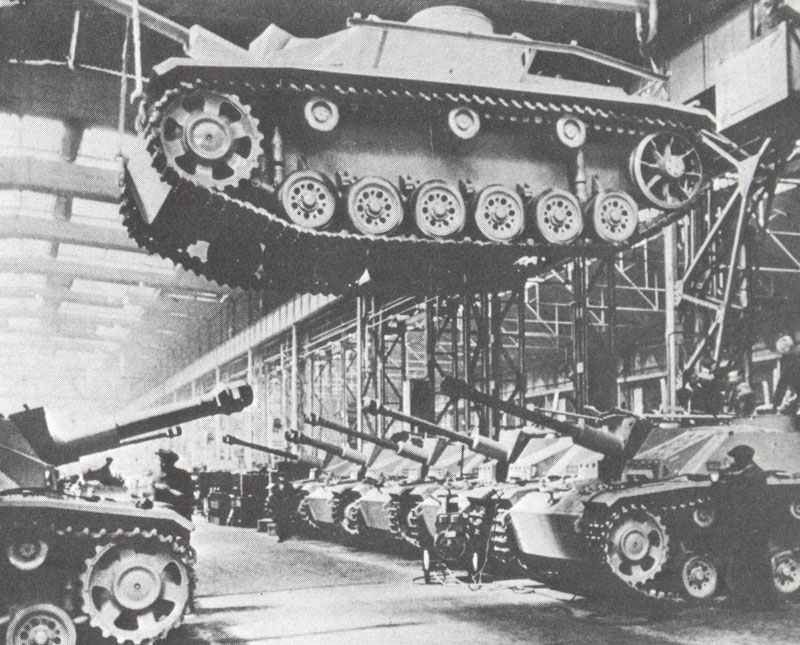

Forming a new army in a war zone was not easy. The Germans refused to release the 600,000 Italian soldiers they had captured on 8 September, as they were to be used in the German armaments’ industry. However, Mussolini was allowed to recruit 13,000 volunteers from these men.

By March 1944, the fascists had managed to bring 60,000 men under arms. Between September and November 1944, the first four divisions that had been sent to Germany for equipment and training returned to Italy. They fought alongside the Germans for the remainder of the Italian campaign.

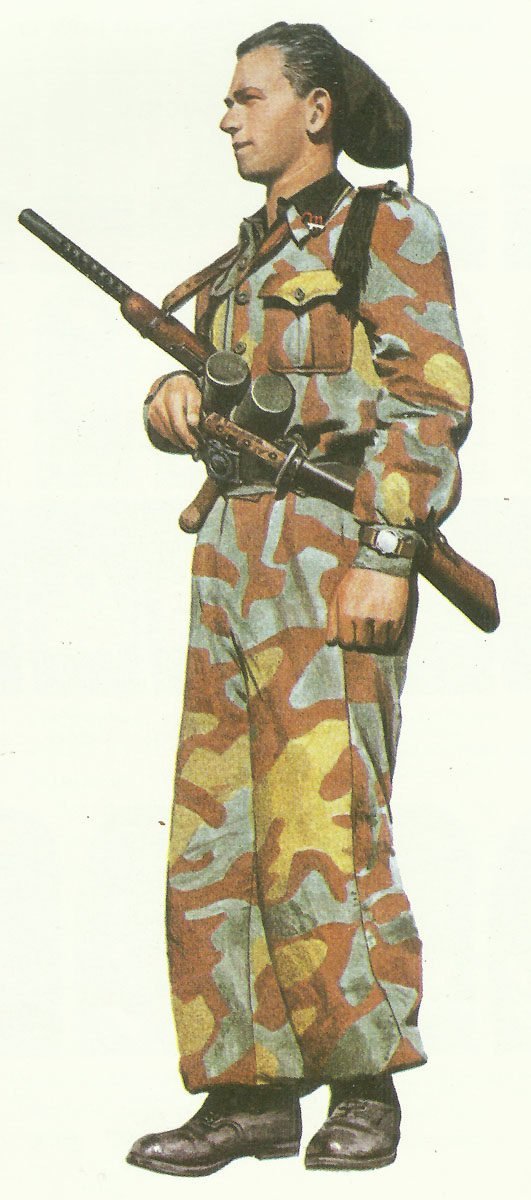

Uniform

However, all monarchist symbols were removed from the insignia and the five-pointed star was replaced by a Roman sword (‘Cladio’) in a laurel wreath, which became the symbol of the RSI.

A new dress code was introduced in late 1944 to bring the Italian uniform more in line with the German look, but the general war and supply situation meant that these regulations never really came into force and only a few senior officers actually wore them.

The RSI was far too preoccupied with its fight for survival against the Allies and the internal threat from communist and royalist partisans to give much thought to its uniforms.

Both officers and enlisted men added to the confusion by using the most varied and eccentric styles in their dress. The pointed Bustina was widely worn as headgear, alongside the Alpini hat and the Bersaglieri fez.

Rank insignia

The rank insignia were moved from the cuffs to the shoulder straps, but the new pattern of rank insignia from the September 1944 regulation was never introduced.

The divisions trained and equipped in Germany adopted German rank insignia as a practical measure to enable the German instructors to immediately recognise the ranks of the Italian officers and men. After their return to Italy, however, the German rank insignia were generally removed.

New coloured insignia and collar patches were introduced to indicate rank.

Paramilitary forces

The GNR, made up of former members of the Carabinieri militia (which had also been disbanded because it had been loyal to the king) and former members of the Italian African police, was used for both military and civilian police duties.

With the constitution of the Socialist Republic, former members of the old fascist cadres (squadristi) reappeared and began to comb the country in search of ‘traitors’. Pavolini, secretary of the National Fascist Party, wanted to use the Squadristi in the war against the internal resistance and against the partisans, and so on 26 July 1944 the Black Brigades were founded as an armed force of the Fascist Party.

Notorious for their cruelty in the service of the German security forces (SS, SD and police), the Black Brigades represented the best and at the same time the worst elements of the Socialist Republic: decorated heroes, child mascots, common criminals, opportunists and idealists.

Uniform:

The National Guard retained the collar tabs and black shirt of the militia (MVSN), but adopted a pair of red letters ‘M’ (for Mussolini) in place of the Gladio.

In reality, however, an astonishing variety of extravagant and irregular uniforms and insignia of personal invention were worn, the common denominator of which was the skull and crossbones and mottos, all of which included death.

RSI Air Force

After the Italian surrender, the Germans had confiscated all available Italian aeroplanes and equipment and taken pilots and technicians prisoner. Botto managed to get most of it back, but his clashes with General Wolfram von Richthofen and German attempts to incorporate the RSI air force into the German Luftwaffe meant that the Italians were not operational until October 1943.

Between January 1944 and April 1945, they managed to shoot down 240 Allied aircraft, mainly B-17 Flying Fortresses and B-24 Liberators.

The main strength of the RSI air force lay in fighter and torpedo aircraft. There was a bomber squadron, but this was sent to the eastern front for political reasons.

Torpedo planes operated against the Allied fleet in the Mediterranean from March 1944 and in June of that year they also took part in the bombing of Gibraltar.

After September 1943, the uniform of the Air Force of the Socialist Republic remained practically unchanged, only the star on it was replaced by the Gladio.

Navy of the RSI

The RSI’s naval forces were called the ‘Marina Nazionale Repubblicana (MNR)’, sometimes also referred to as the ‘Marina della RSI’.

Only a few members of the navy joined Mussolini’s MAS flotilla, which instructed German combat swimmers in the use of small warboats and, together with them, carried out attacks on Allied ships, which by this time had already taken routine precautions against such attacks.

About a dozen MAS boats and small submarines were deployed there. However, most of the ex-Italian ships were taken over and manned by the German navy. As a result, the Fascist navy reached only five per cent of the size of the ‘Co-Belligerent’ fleet of the Italian kingdom to the south.

The RSI Navy was extremely limited in resources, ships, and personnel, as most of the Italian fleet had either joined the Allies or been interned. The Germans seized many ships and used them under Kriegsmarine control, sometimes with Italian crews. The RSI Navy operated mainly in the Adriatic and Ligurian Seas, focusing on anti-partisan, escort, and minelaying duties, as well as special operations.

Main Ships and Units of the RSI Navy (1944-45):

Torpedo Boats (Torpediniere)

– TA series: Several former Italian torpedo boats were taken over by the Germans (designated as TA, e.g., TA20, TA23, etc.), but some were crewed partly by RSI personnel.

– Notable examples: TA20 (ex-Italian Audace) operated with mixed German/Italian crews; TA35 (ex-Corsaro) with similar arrangement.

MAS Boats (Motoscafo Armato Silurante)

– Several MAS (torpedo motorboats) were operated by the RSI, especially in the Adriatic and northern Tyrrhenian Sea. These were used for attacks on Allied shipping, minelaying, and anti-partisan operations.

CB-class Midget Submarines

– A handful of CB-class midget submarines (40-ton, 4-man) were operated by the RSI, mainly in the Adriatic. Some were used in the Black Sea under German/Italian command.

Submarine Chasers and Patrol Boats

– Small numbers of ex-Italian submarine chasers and patrol boats were used for coastal defense and anti-partisan operations.

Motor Torpedo Boats (MTBs)

– MS (Motosilurante) boats: Several MS-type boats were used by the RSI for fast attack and patrol missions.

Special Assault Craft

– The RSI continued to operate some Decima Flottiglia MAS units, which used special craft like:

– MTM (Motoscafo da Turismo Modificato): Explosive motorboats.

– SLC (“Siluro a Lenta Corsa”): Human torpedoes (“Maiale”).

These units conducted sabotage and commando raids, sometimes in cooperation with the German Kriegsmarine.

Auxiliary and Support Vessels

– A variety of small auxiliary ships (minesweepers, tugs, transports) were pressed into service.

Notable Units and Formations

– Decima Flottiglia MAS: Under Junio Valerio Borghese, this famous commando unit remained active under RSI control, conducting raids, sabotage, and anti-partisan actions.

– Gruppo di Combattimento di Superficie: Surface combat group, mainly for coastal defense.

– Gruppi di MAS: MAS flotillas for torpedo and patrol missions.

Notable Limitations

– The RSI Navy had very few large ships—no battleships or cruisers were available.

– Most operations were coastal or inshore.

– Many ships were under German command or operated with mixed German/Italian crews.

The lace on the cap band to distinguish ranks was replaced by different patterns of chin straps, which were blue and gold for lower officer ranks and gold for higher ranks.

The traditional sailor’s cap was no longer used and was replaced by a blue beret with a small gold-plated metal anchor on the front.

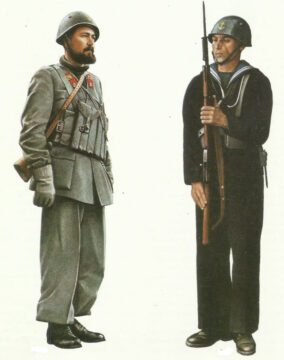

From 1943, the republican marines received the grey-green uniform of the paratroopers (see illustration on the right).

Italian Co-Belligerent Forces

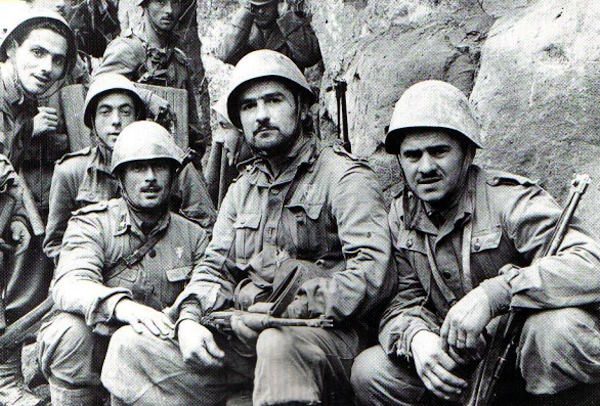

On 28 September 1943, the Kingdom’s first military unit in southern Italy was formed as the First Motorised Combat Group (1st Raggruppamento Motorizzato) with a strength of 295 officers and 5,387 men. Its first deployment was in the Cassino sector on Monte Lungo and played a key role in dispelling the Allies’ mistrust of Italian soldiers fighting on their side.

After its deployment with the American 5th Army and the reorganisation, the Raggruppamenio was transferred to the Polish corps on the extreme left wing of the British 8th Army. On 17 April 1944, the now 22,000-strong formation was given the name ‘Italian Liberation Corps’ (Corpo Italiano di Liberazione) and consisted of the core of the 184th Nembo Paratrooper and Utili Infantry Division. In September and October 1944, the corps was split into four Gruppi di Combattimento and the direct successor unit was the ‘Folgore’. In addition, the groups ‘Cremona’ (core of the 44th Infantry Division), ‘Legano’ (core of the 58th Infantry Division) and ‘Friuli’ (core of the 20th Infantry Division) were formed.

Each Gruppi di Combattimento consisted of two infantry and one artillery regiment, a mixed battalion of sappers, two detachments of carabinieri (military police) and administrative services with a total of 400 officers and 9,000 men.

The first six of these groups arrived at the front in early 1945, but political considerations led the Allies to play down the role of the royalist troops in the victory in Italy.

Another important element of the Italian forces on the Allied side were, of course, the partisans. However, they were inconsistently organised and uniformed.

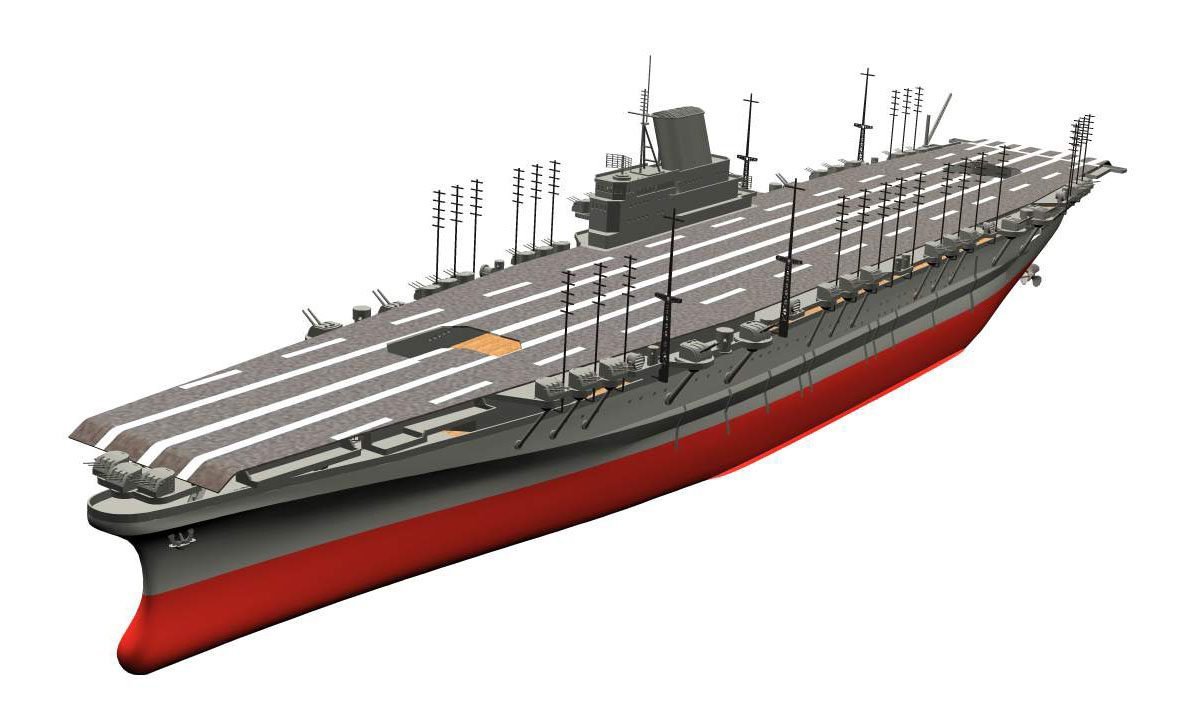

Co-Belligerent fleet

The Italian navy played an important role after the armistice was signed. A total of five battleships, eight cruisers, 33 destroyers, 39 submarines, 12 MTBs, 22 escort ships and three minelayers of the Regia Navale formed the Co-Belligerent fleet. There were also four squadrons of seaplanes from the Regia Aeronautica.

The Italian Chief of Staff set up his headquarters in Taranto, but three cruisers were soon detached to hunt blockade runners in the South Atlantic.

Other ships were used for various tasks in the Mediterranean after being repaired and overhauled. One of the most important contributions of the Italian Navy was its help in restoring Italian harbours to supply Allied troops.

In addition, Italian frogmen, together with British mini-submarines, sank two cruisers and the aircraft carrier Aquila, which were in harbours occupied by German troops.

Uniform

The lack of supplies of any kind – partly due to Allied bombing raids and partly due to German confiscations – forced the Italians in the south to adopt Allied uniforms and equipment. Their choice fell on English uniforms, on which the Italian insignia continued to be used unchanged.

The Bersaglieri and the Alpini also attached their respective plumes to the British steel helmet.

As it seemed necessary to be able to distinguish the Italians from the other Allied troops, a rectangular badge in the Italian national colours was introduced, which was worn at the top of the left sleeve. The emblem of the respective combat group was printed in black on the white of the Italian tricolour.

Officers moved the rank insignia from the cuff to the shoulder straps. The uniforms of the royalist air force and navy did not undergo any major changes compared to the time before the Italian capitulation.

References and literature

The Armed Forces of World War II (Andrew Mollo)

The Italian Army 1940-45 (3) – Italy 1943-45 (Philip Jowett, Stephen Andrew)

World War II – A Statistical Survey (John Ellis)

The Italian Navy in World War II (Erminio Bagnasco)

Italian Warships of World War II (Aldo Fraccaroli)

The Decima MAS (Orazio Ferrara)