Strength and Organization of the Regia Aeronautica and Regia Navale when Italy enters Second World War in June 1940.

Regia Aeronautica and Regia Navale

Table of Contents

Italian Air Force (Regia Aeronautica)

The Regia Aeronautica was the air force of the Kingdom of Italy during World War II.

Overview

Pre-war situation: Italy entered the war in 1940 with a large air force, but many of its aircraft were obsolete.

Early successes: The Regia Aeronautica performed well in the early stages of the war, particularly in North Africa and the Mediterranean.

Notable aircraft: Some of the more successful Italian planes included the Macchi C.202 Folgore and Macchi C.205V Veltro fighters, and the CANT Z.1007 bomber.

Limitations: The Italian air force suffered from a lack of resources, inadequate pilot training, and limited industrial capacity to produce modern aircraft.

North African Campaign: Italian air units played a significant role in supporting Axis ground forces in North Africa, but were gradually overwhelmed by superior Allied numbers and technology.

Mediterranean operations: The Regia Aeronautica was active in the Mediterranean, supporting naval operations and attacking Allied shipping.

Defense of Italy: As the war progressed, the air force increasingly focused on defending Italian territory from Allied bombing raids.

Armistice and split: After Italy’s armistice with the Allies in September 1943, the air force split into two factions – one supporting the Allies and another supporting the German-backed Italian Social Republic.

Post-armistice: Some Italian pilots continued to fight alongside the Germans, while others joined the Allied-aligned Italian Co-Belligerent Air Force.

Legacy: Despite some notable achievements, the Regia Aeronautica was generally outmatched by its Allied counterparts in terms of equipment, numbers, and strategic effectiveness throughout the war.

Italian air force at the outbreak of war

On 24 January 1923 the Italian Royal Air Force (Regia Aeronautica) was formed as an independent arm, separate from the air services of the Army and Navy and in 1925 the establishment of an Air Ministry put the new service on a secure footing. During the inter-war years the Italian Air Force was held in high regard: Italian planes were technically advanced, and her Air Force commanders, who included the aerial theorist Giulio Douhet, were considered to be amongst the most progressive and imaginative in Europe. And yet by 1940 the Air Force was in decline.

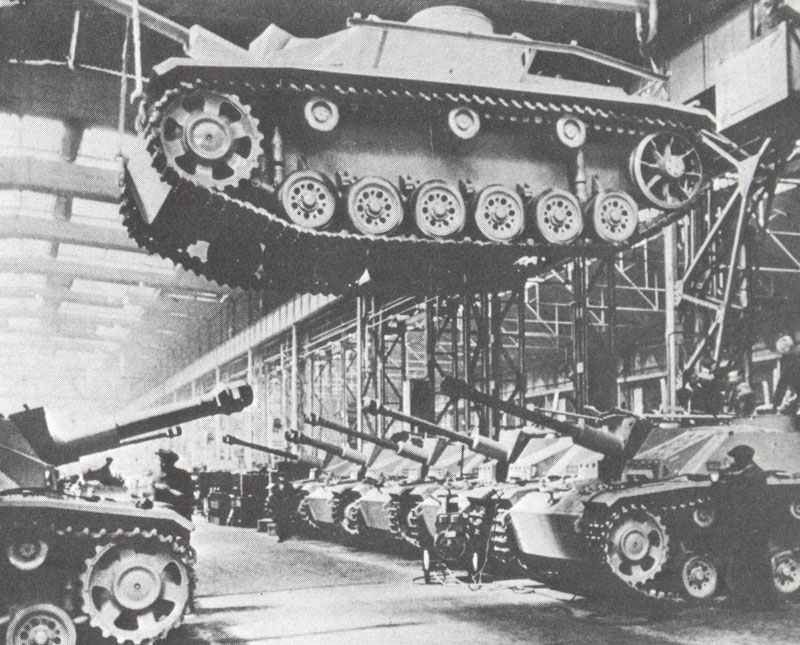

Having built up a modern air force in the ‘twenties and ‘thirties, Italy did not develop it further with the result that at the outbreak of war Italy’s front-line planes were largely obsolescent. During the course of the war attempts were made to replace the Fiat CR-32 and CR-42, the mainstay of Italy’s fighter arm, but the industrial and technical weakness of the country failed to produce a plane in sufficient quantities that remedied the Italian problem of poor armament and a weak power-plant.

A further serious problem facing the Air Force was the defense of Italy’s colonial possessions and its over-commitment in fulfilling Mussolini’s grandiose designs.

Following the declaration of war on 10 June 1940, the Italian Air Force engaged with its French and British counterparts throughout the Mediterranean. Initially the Italian Air Force did reasonably well but with the introduction of the RAF’s Hawker Hurricane towards the end of 1940 the balance of forces was tipped to the Allies’ advantage.

During October 1940 Mussolini despatched an expeditionary force to Belgium in order to take part in the Battle of Britain. But once pitted against RAF Fighter Command on its home ground, the mixed Italian fighter and bomber force was badly mauled and was retired to defensive duties.

In Italian East Africa the Air Force provided the Army with reconnaissance and ground support services. The sides were fairly evenly matched, but the Italian Air Force was worn down in a battle of attrition. Italian pilots fought on to the bitter end until the last aircraft was shot down on 24 October 1941.

In 1940 the Italian Air Force was divided into four Territorial Air Zones which covered metropolitan Italy and five overseas Commands. While the Air Force was an independent service within the Italian armed forces there was an Army air force of 37 squadrons which was attached directly to the ground forces as well as a Navy air service of 20 squadrons of sea-planes and flying-boats and ten squadrons of transport aircraft.

There were 12,000 pilots and aircrew, 6,100 non-flying officers and 185,000 other ranks in the Air Force in 1940.

The basic tactical unit was the squadron (squadriglia) which had a strength of around nine aircraft with another three in reserve, although bomber squadrons usually had only six front-line planes.

Two or three squadrons formed an air group (gruppo) and two or more groups would form a wing or stormo, the basic tactical formation within the Air Force. Two or three wings would on occasion combine to form an air brigade which in turn with another brigade would form an air division. The largest formation in the Air Force was the air fleet which consisted of two or more homogeneous fighter or bomber air divisions.

The forces within the Territorial Air Zones based in Italy were organized as follows:

- Northern Zone: 7 wings of bombers (approx. 315 planes) and 3 wings (plus one group) of CR-42 fighters (approx. 210 planes);

- Central Zone: three wings of bombers (approx. 135 planes) and two wings and a group of fighter planes (approx. 150 planes);

- Southern Zone: five bomber wings (approx. 225 planes) and one fighter wing as well as an autonomous fighter group (approx. 90 planes) and dive bomber group (approx. 25 planes);

- South-Eastern Zone: one wing of night-bombers (approx. 45 planes) and float-planes and a group of obsolescent CR-32 fighters (approx. 30 planes).

- the largest of the overseas commands was that based in Libya and comprised four bomber wings (approx. 180 planes) ; a fighter wing and three other fighter groups (approx. 150 planes) ; and two groups plus two squadrons of colonial reconnaissance aircraft (approx. 60 planes).

The Italian Air Force begun the war with nearly 2,000 operational aircraft ready for combat and with almost the same number in reserve.

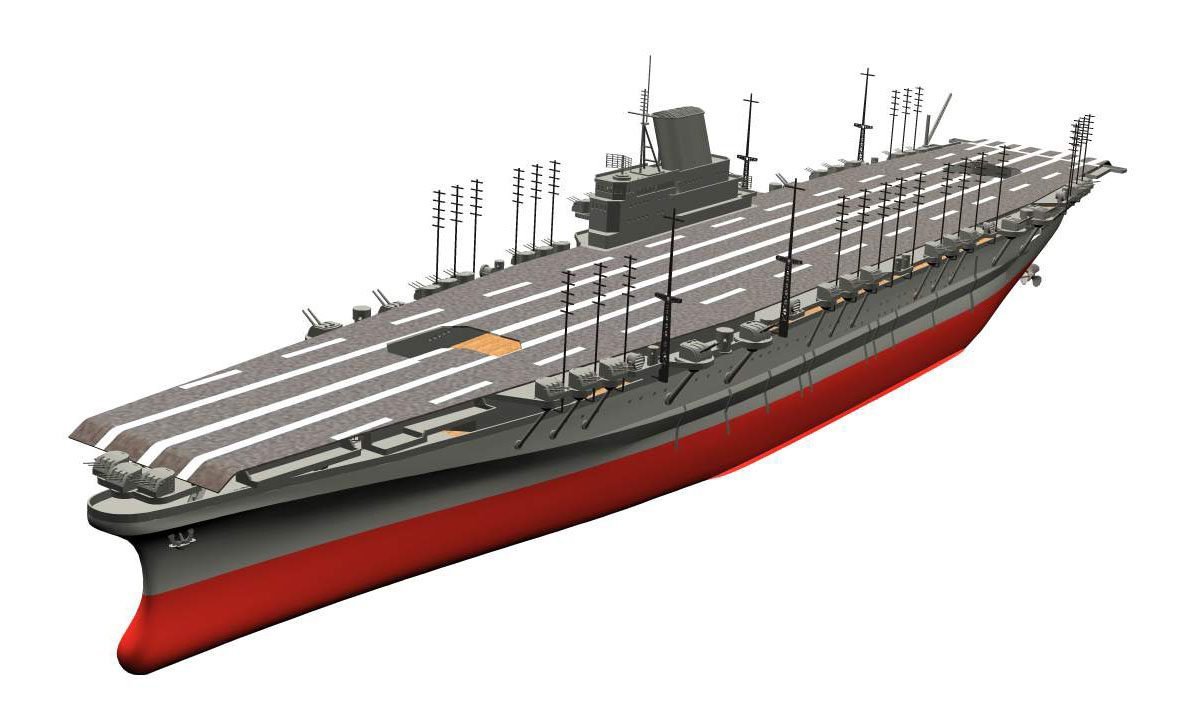

Italian Navy (Regia Navale)

Mussolini hoped that the Regia Navale would play an important part in any Mediterranean war. He saw control of the sea (Mare Nostrum – Our Sea – was how he described the Mediterranean) as an essential prerequisite for expanding his empire into Nice, Corsica, Tunis and the Balkans.

Italian naval building accelerated during his tenure of power, and by June 1940, the Navy comprised:

- 4 battleships;

- 8 heavy cruisers;

- 14 light cruisers;

- 128 destroyers;

- 115 submarines;

- 62 motor-torpedo boats.

There were also four battleships fitting out. The personnel of 4,180 officers and 70,500 ratings was expanded rapidly on mobilization, until there were, on average, 190,000 men serving at any time between 1940 and 1942.

The surrender of the French fleet in June 1940 seemed to offer a great opportunity to the Regia Navale; one of its main rivals had been removed at a stroke. But although the main Italian vessels were modern, fast and well-armed, and (in spite of graceful lines) had considerable armored protection, the Italian vessels were overborne by the might of the British Royal Navy. Early defeats at Taranto and Matapan, although not crippling in themselves, confirmed British superiority; the absence of both radar and a proper fleet air arm were considerable handicaps; and a shortage of fuel proved a progressively crippling brake on operations. Only the small attack craft lived up to expectations, in many brave and successful actions.

From June 1940 to September 1943, the Navy lost one battleship and 13 cruisers, out of total losses of 339 ships of all types, and 24,660 men.

The supreme commander of the Italian armed forces and Minister of Marine was Benito Mussolini, but executive control was exercised by the Under-Secretary and Chief of Naval Staff (Supermarina) Admiral Domenico Cavagnari. Commander-in-Chief of the Fleet was Admiral Campioni. Departments of the Ministry of Marine and the Naval Staff undertook the customary responsibilities of the admiralty, with one exception. The Ministry of Marine submitted design requirements to a separate department which catered for the needs of all three services. Examples of this were the battleships Littorio and Vittorio Veneto, projected by General Umberto Pugliese, whose team supervised the arrangements for their construction by Ansaldo at Genoa and CRDA at Trieste.

The Navy was organized in two squadrons with torpedo-boats, submarines, training and reserves forming four main sub-divisions.

When Italy entered the war on 10 June 1940, the Regia Navale was disposed as follows:

The Taranto Command, which included Messina and Augusta, comprised: 2 battleships in divisions of 2 to 4 vessels, each commanded by a divisional rear-admiral. Several divisions were grouped together under a vice-admiral:

44 destroyers and torpedo-boats in divisions of 2 to 4 vessels;

22 submarines;

16 motor torpedo-boats in flotillas;

2 mine layers;

4 escort and patrol boats.

The Venice (Adriatic) Command including Brindisi and Bari comprised:

8 destroyers and torpedo-boats;

4 submarines;

16 motor-torpedo boats;

I escort and patrol boat.

La Spezia Command including Cagliari consisted of:

21 destroyers and torpedo-boats;

36 submarines;

26 motor-torpedo boats;

1 mine layer;

3 escort and patrol boats.

The Naples Command consisted of:

4 cruisers;

18 destroyers and torpedo-boats;

11 submarines;

6 motor-torpedo boats;

3 mine layers;

1 escort and patrol boat.

The Sicily-Libya Command, which included Syracuse, Palermo, Tripoli and Tobruk, consisted of:

1 cruiser;

24 destroyers and torpedo-boats;

26 submarines;

12 motor torpedo-boats;

2 mine layers;

3 escort and patrol boats.

The Dodecanese (Leros) Command comprised:

6 destroyers and torpedo-boats;

8 submarines;

20 motor torpedo-boats;

1 mine layer.

The Red Sea (Massawa) Command (which was destroyed in April 1941) comprised:

9 destroyers and torpedo-boats;

8 submarines;

5 motor torpedo-boats;

4 escort and patrol boats.

There were 1,235 Italian merchant ships, totaling 3,448,453 tons.

The Navy lacked aircraft, and was dependent on the Air Force for protection and reconnaissance. This was an unsatisfactory state of affairs; co-operation was poor, and although the torpedo-bombers and reconnaissance aircraft of the Regia Aeronautica were effective, high-level bombers did not have much success against ships at sea.

References and literature

The Armed Forces of World War II (Andrew Mollo)

Luftkrieg (Piekalkiewicz)

World War II – A Statistical Survey (John Ellis)

Flotten des 2. Weltkrieges (Antony Preston)

It’s Regia Marina, not Regia Navale.