The British Army in Southeast Asia 1941 to 1945.

Organization, divisions, Orders of Battle 1941/1942 and 1945, uniforms.

The British troops fighting in Burma saw themselves as the ‘Forgotten Army’ in the Allied war effort. At the same time, their campaign was probably the toughest in which British troops were involved anywhere, especially in terms of terrain and climate, but also in terms of their fanatical opponents.

Therefore, supply and medical problems took on a significance that at times pushed the actual combat mission into the background. The enemy, which they also fought against, made up for its inadequate logistics with a cruelty and toughness that had rarely occurred during military operations.

British Army in Southeast Asia

Table of Contents

The campaign in the Far East was divided into three main phases:

- First, the loss of Hong Kong and Malaysia and the withdrawal from Burma;

- Second, a period of defensive consolidation with smaller offensive operations in the Arakan and the deployment of Chindit raids;

- Third, a victorious advance through Burma.

The initial defeat was mainly due to the use of inappropriate forces, underestimation of the enemy, and the as yet unknown problems of jungle warfare. At the same time, it had a negative effect that many units had to surrender their experienced officers and non-commissioned officers in order to serve as cadres for new formations.

When the Japanese attacked in December 1941, the long dispute between the three British services over the strategic deployment of their respective armed forces continued to rumble in the background.

Despite the creation of a Supreme Command and the new appointment of a Commander-in-Chief in the Far East in November 1940, defense was far from sufficiently coordinated.

There were two commanders-in-chief in Singapore, the General Officers Commanding in Burma, Malaya and Hong Kong, who were responsible to the War Ministry. In addition, there were the governors of Hong Kong, Burma and the Straits Settlements, who were subordinated to the Colonial Office.

The troops in India were under the command of their own commander-in-chief and were only given the mandate to defend Burma on 12 December 1941.

The command over the theater of war in Southeast Asia was further complicated by the creation of the ABDA (American-British-Dutch-Australian) Supreme Command for the Southwest Pacific on January 4, 1942.

Organization

The focus of British troop concentrations in Southeast Asia outside India was on Malaya, Singapore, Ceylon, Burma and Hong Kong. The two battalions that formed the North China garrison in the city of Shanghai had already been withdrawn in August 1940.

There were also two infantry battalions at the garrison of Hong Kong, at the mainland infantry brigade and island infantry brigade under the headquarters of the ‘China Command’.

The two British battalions in Burma each had only two infantry companies in December 1941, and they were therefore deployed in the 1st Burma Brigade and Garrison of Rangoon.

Reinforcements with further British troops arrived in Malaya and Burma, especially the 18th Infantry Division and the 7th Armored Brigade, the latter with only two of its three regiments.

Of the 38 battalions that defended Singapore until its surrender, 13 were completely British.

The defense of India and Ceylon, and in particular measures to ensure internal order there, tied up a large amount of available troops in the Far East. In August 1942, for example, 57 battalions were deployed to contain internal unrest in India.

The danger of political unrest in the Crown Colony had become increasingly alarming since the outbreak of war in Europe, after many regular units stationed in India had been transferred to Britain or the Middle East. These were replaced by territorial troops who were naturally unfamiliar with the Indian subcontinent and its population.

British Orders of Battle: Malaya, Hong Kong and Burma December 1941 – February 1942 and in India on 21 April 1942:

| Headquarter | Army/Command | Corps | Divisions |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABDA Commando (from 25 Dec 1941) | Malaya Command | Reserves | 12 Indian Inf.Brigade (from January 1942 arriving: 18 British Inf.Div., 44 and 45 Indian Inf.Brigade from 17 Indian Inf.Div.) |

| III Indian | 9, 11 Indian Inf.Div., 28 Indian Inf.Brigade | ||

| Fortress Singapur | 1, 2 Malayan Inf.Brigade | ||

| A.I.F. | 8 Australian Inf.Div. | ||

| Hongkong Garrison | Mianland Brigade, Island Brigade (total 2 British, 2 Indian and 2 Canadian Battallions) | ||

| Burma Army | Reserves | 16 Indian Inf.Brigade (arriving in Jan and Feb 1942: HQ 17 Indian Inf.Div., 46, 48, 63 Indian Inf.Brigade, 7 Armored Brigade) | |

| Garrison Rangoon, 1 Burma Div. | |||

| C-in-C India | Eastern Army | Reserves | Assam Inf.Div., 1 British Inf.Brigade |

| XV Indian | 14, 26 Indian Inf.Div. | ||

| IV Indian | 23, 70 Indian Inf.Div. | ||

| Southern Army | 19, 20 Indian Inf.Div., 50 Tank-Brigade, 251 Indian Armored Brigade |

The army in India was divided into three command areas: the North, East and South Commands. On April 21, 1942, however, the Indian command was reorganized and it was subordinated the mass of training camps and facilities to it, as well as three armies. These were the South, East and Northwest Armies.

The East Army, which was responsible for the defense of Assam, Bengal, Bihar and Orissa, naturally became the mainly active command, and the 14th Army was formed mainly from the units there in October 1943.

The land forces of the SEAC consisted of the 14th Army and the Army Command Ceylon and were combined under the new headquarters of the 11th Army Group.

The 14th army consisted of the XV Corps (5th, 7th Indian divisions and 81st West African division) and the IV Corps (17th, 20th, 23rd and 26th Indian infantry division and the 254th Indian tank brigade).

The XXXIII Corps (2nd British and 36th Indian Infantry Division) was also assigned to the South East Asia Command, but remained subordinated to the India Command, as were the 19th and 25th Indian Divisions and the 50th Tank Brigade.

The most important formations of the Ceylon Army Command were the 11th East African Division and the 99th Indian Infantry Brigade.

The most important special unit was the 3rd Indian Division, which included the Chindits Deep Penetration Groups under Major General Orde Wingate.

The first of these LRP (Long Range Penetration) groups were set up in July 1942 as the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade. However, these were brought to a strength of six infantry brigades (14th, 16th, 23rd, 77th, 111th and 3rd West African) by the dissolution of the 70th British Division and a suitable brigade of the 81st West African Division.

Each of these special commando brigades consisted of a number of columns composed of either British or Gurkhas. The British columns were 306 men and the Gurkhas 369 men of all ranks strong.

Each column had an RAF section, a medical section, signalers, a sabotage group, a platoon of Burma rifles, an infantry company and a support group.

At full TOE strength and including division services and associated units, the Chindits combined were about two divisions strong.

Orders of Battle Southeast Asia Command April 1945:

| Command | Army | Corps | Divisions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indian Army Command | 14, 23, 39 Indian Inf.Div., 44. Indian Airborne Div. (all Training formations) | ||

| Allied Land Forces Southeast Asia | XV | 81, 82 West African Div., 3 Commandos Brigade | |

| Northern Area Combat Command | transfer to Indo-China | 2 British Inf.Div. | |

| 36 British Inf.Div., US 'Mars' Force | |||

| new Chinese First Army | 30, 38 Chinese Inf.Div. | ||

| new Chinese Sixth Army | 14, 22, 50 Chinese Inf.Div. | ||

| 14th Army | Reserves | 25, 26 Indian Inf.Div., 11 East African Inf.Div. | |

| IV | 5, 17, 19 Indian Inf.Div., 255 Indian Tank Brigade | ||

| XXXIII | 7, 20 Indian Inf.Div., 254 Indian Tank Brigade | ||

| India-Burma Theater | total 12 Chinese Infantry divisions in Yunnan | ||

| China Theater | (not relevant for this orders of battle) |

Thus, the 14th Army headquarters was moved from Burma back to India to lead the invasion of Malaya, and in Burma the new 12th Army, activated on 28 May 1945, took over command.

The 14th Army, which was nearly 1 million men strong in 1944 and early 1945, was the largest single army of the Second World War and was finally disbanded on December 1, 1945.

At various times, the army had up to four corpses (IV, XV, XXXIII and XXXIV) and included a total of 13 divisions. These were the 2nd and 36th British, 5th, 7th, 17th, 19th, 20th, 23rd, 25th and 26th Indian, 11th East African and 81st and 82nd West African divisions.

British losses in Burma between 11 December 1941 and 15 September 1945 totaled 25,170 officers and men. Of these, 6,921 were killed in action, 15,585 wounded and 2,664 were missing or prisoners of war.

In the Second World War, the entire British Army suffered 569,5091 casualties. Of these, 144,079 were killed, 239,575 wounded, 33,771 missing and 152,076 were taken prisoner of war.

Uniforms

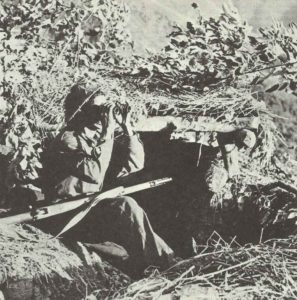

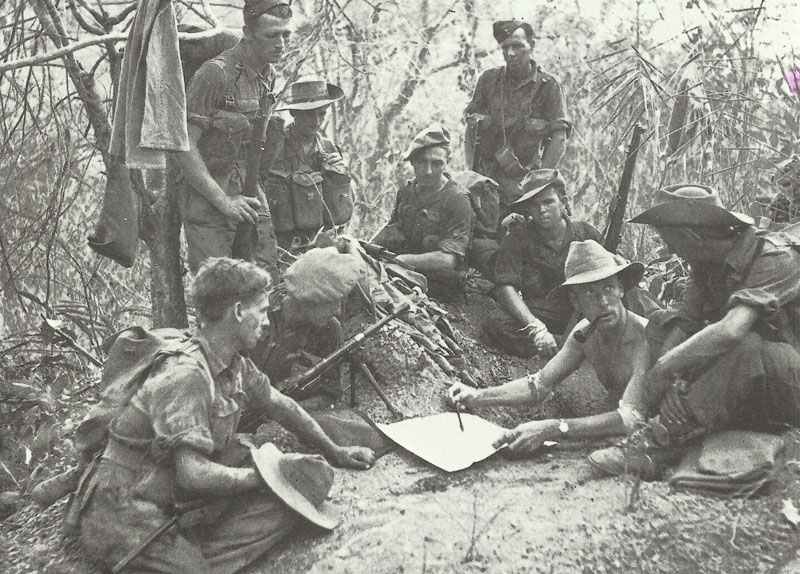

In 1942 a new jungle green uniform was introduced, which had become the standard until the campaigns of 1943 and 1944.

This basic uniform was made of jungle green cellular material and consisted of a bush jacket and a shirt with long and short sleeves and long and short trousers. Different types of regimental headgear were worn when not in action. At the front line however, the most frequent headgear was the steel helmet or the slouch hat.

The web equipment was often painted dark green or black to improve the camouflage of clothing and make it less sensitive to moisture in the jungle.

Like the Australian jungle fighters, the British soldiers and those from the Dominions in Burma wore their equipment in a manner suitable for the jungle.

Badges of rank were worn as with ordinary European uniforms, with the exception that metal badges were often painted black. NCO’s chevrons were displayed with normal tape. Formation or rank badges were only sometimes worn in a special way (as the soldier in the picture right).